The More Things Change

Heather Havrilesky On The Response To Her Marriage Memoir & Raising Daughters Who Know Cringe When They See It

“To land in this place over and over again, it’s funny as hell, but it’s also so frustrating because nothing changes.”

I think a lot about how things have — or haven’t — progressed since I was a teenager in the 1990s, poring over Sassy and listening to the Breeders. In my junior year of high school, Ruth Bader Ginsburg took her seat as the second woman on the Supreme Court, and in the interim there’s been a sea change in terms of how we talk about everything from our bodies to rape culture, the mental load — even, thank goodness, Monica Lewinsky. Why, we actually sometimes permit ladies with gray hair to appear on magazine covers! One might, at times, find oneself thinking, We’ve come a long way, baby.

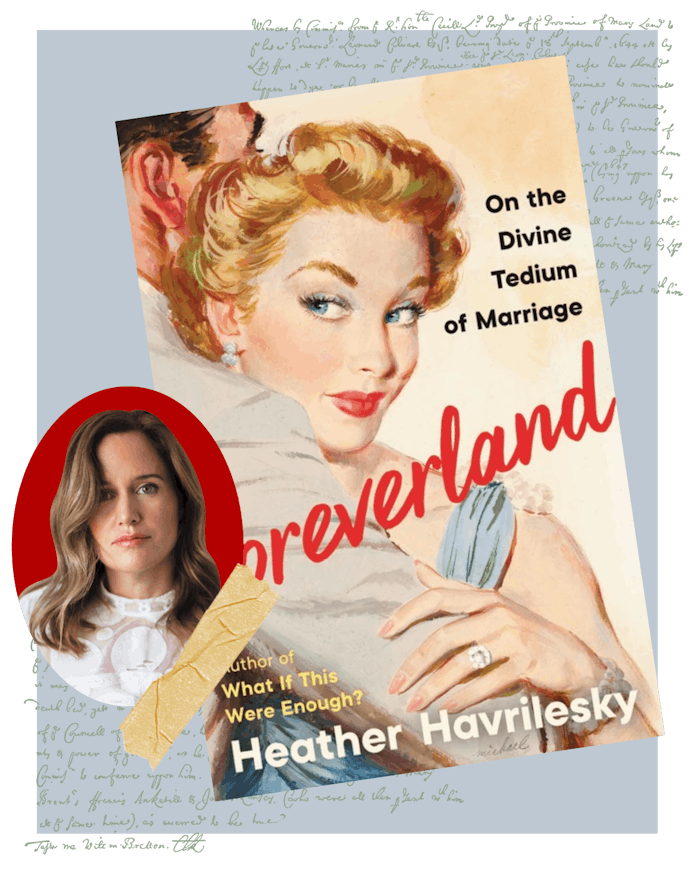

But then I’ll be reminded that our culture is maddeningly slow to evolve and we’re still litigating the same questions about female identity over and over: What does it mean to be a good wife? To be a good mother? And what the hell do either of those things have to do with who we are as professionals, or with the work we produce as writers, artists, creatives? You can see this tiresome conversation play out once again in the response to Heather Havrilesky’s hilarious, moving, tender new memoir, Foreverland: On the Divine Tedium of Marriage. And it all starts to feel like the more things change…

A longtime fan of Havrilesky’s writing, I’d been looking forward to the book for months. When, ahead of the release, a chapter appeared as an excerpt in The New York Times titled “Marriage Requires Amnesia,” I wasn’t shocked by the mixed response. Comments on The Times’ Facebook page and around the wonderful world of social media seemed split between the “Married 45 years and loved this!” sentiment and the “Married my best friend almost 23 years ago … It has never felt like work at all! / I hope the author is getting therapy” variety. I personally found it astonishing that not everyone in a marriage could relate, but, hey, humans are mysterious!

I read the book myself over the course of a recent weekend while my own husband of 15 years sniffled and coughed himself into a sad state, victim of his first Man Cold in two years. Havrilesky’s honest portrait of her marriage — and of the idea of marriage, impossible, ridiculous, beautiful! — is not only extremely amusing, but raw, poignant, and generous of heart. By the end of the book, I found myself less annoyed with my own poor spouse, and also a little in love with Havrilesky’s.

The slate of official reviews has run the gamut from glowing, thoughtful, and nuanced to predictably patronizing, predictably lurid, and predictably totally sexist. Many headlines in the latter camp failed to use Havrilesky’s name, let alone describe her as an accomplished author and cultural critic — she’s just “Wife” or “Woman, 51.” Ultimately, though, it was a segment on The View that really finally pushed me, Havrilesky, the Twitterverse, and even Havrilesky’s own daughters, ages 12 and 15, into full disgust mode.

“There’s a new book by journalist, wife, and mom,” starts Whoopi Goldberg — and right then and there, we can tell where it’s heading. Without (ever) naming Havrilesky, Goldberg continues, “who reflects on her 16 years of marriage, writing about how she hates her husband, calling him a ‘smelly heap of laundry’ and a ‘snoring heap of meat,’ and claims anyone considering getting married is a masochist.” The hosts failed completely to put these lines into context — to understand the humor and searching candor with which Havrilesky approached her subject or to even say Havrilesky’s name, as if they were gossiping about a local PTA mom-gone-wild rather than an accomplished writer and cultural critic.

We sure have a long way to go, baby. Or at least, some of us do.

A bit of good old-fashioned outrage burst forth from my fellow Havrilesky fans on social media, and best of all, we got a glimpse of her daughters’ reactions — they seemed to be more baffled and embarrassed for the women of The View than anything.

Below, I spoke with Havrilesky about The View, being a woman raising women while battling the archaic, sexist, ageist toxicity that’s still so pervasive in the very air we breathe, and what’s truly, thankfully, changing for our kids.

Why did The View coverage, out of all the press the book has received, strike such a chord?

I think what makes me angry about The View is that they had exactly two phrases from my book that they kept repeating. I saw no evidence that they knew anything but “smelly heap of laundry, snoring heap of meat.” Which is — that’s writing. That’s a chapter I wrote about anger and the point of the chapter is that there are mornings when you hallucinate that your husband is not a person anymore. He’s a thing that’s an obstacle to you getting through your morning. He’s in your way. Here is something in the way, what is it? Oh, God. It’s laundry. No, it’s my husband. Shit. Writing is used to recreate experiences that are layered, and what I’m reaching for in my book is a way to express the positive and negative and everything in between, all of these sensations that you have within a marriage.

To land in this place over and over again, it’s funny as hell, but it’s also so frustrating because nothing changes.

And so, to have a bunch of women sit and talk about eight words from my book as if they’d read it, without naming the book and without using my name at all, ever — that in particular felt insulting, offensive. And it felt like an erasure. Because what man, who has been working for a quarter of a century at something and has written four books, would be treated in the same way? It’s inherently sexist to behave that way.

So, the fact that The View regularly reduces women with names to wife and mom… I mean, if it hadn’t happened before, I don’t think I would feel quite so enraged, but this happened eight years ago.

With the “don’t call me Mom” article.

Yes, in 2014. I wrote a piece about mom culture and about how people walk up to you and address you as Mom. And you say, “You don’t have that relationship with me. Please don’t address me like my name is Mom.” And so, the irony there was that Whoopi started the segment with, “So, some mom.”

I mean, literally, “So, some mom”! Exactly the point I’m making. And the thing is, to land in this place over and over again, it’s funny as hell, but it’s also so frustrating because nothing changes. And so, my whole thing with The View is, Jesus Christ, when are you going to wake up and change? You are making life bad for women. How can you keep doing that without noticing what you’re doing?

Did your daughters see the clip?

Yeah. They were annoyed and then a little bit upset. I said, “I don’t know if you guys should really listen to this. It might be depressing.” And my older daughter was like, “Whatever. Play it. I want to hear it. It’s super cringey, obviously. Do they ever name you? Do they ever use your name?”

And we watch the whole thing. They never say my name. They never mention the book. And my daughters were just like, “Ew. That’s gross. That show is gross.”

Were they surprised?

No. They think a lot of things are cringey.

[Laughs] I know!

You know what I mean! I warned them, right? That this book would be taken in the wrong way in a lot of places. I’ve said to them many times, “If something I do ever becomes massively popular, we’re in trouble. I just want you to know, it won’t be fun for you guys at all. I don’t care, but I worry about you.”

And their reaction is, “Why would we listen to something…” The way the world is now, I think a lot of kids are skeptical because the way that they encounter culture is really interesting. They encounter it through this filter of TikTok and skepticism. They can carefully select the cultural artifacts that they want to engage with and the ones that they don’t want to engage with. And they’ve also lived through Trump and now they’re seeing this war. I mean, a lot of things in the world seem like madness to them.

I do think my kids have a much more flexible sense of what’s interesting, what’s valid, what’s beautiful, what’s unique. They’re much more playful and creative around aesthetics than I think we were.

Even like, Bridget Jones’s Diary: You don’t even have a memory of how weird and regressive the movie is until you watch it with your kids. If you try to show them Pretty in Pink, they’re just like, “What is this nonsense? It moves really slowly and everyone’s sexist and racist. Who wants this?” And you end up asking yourself, “Oh Jesus. What kind of a dinosaur am I?”

We try to urge them to keep an open mind and see the good things, but the world is weird right now for kids. It’s intense.

When you look back at the stuff we were digesting in the ’80s and ’90s and even the early 2000s, it’s so bad. Do you feel like the world that our daughters are in right now is giving them any different messages than we got?

Yes. If you say anything about how someone looks or is shaped, my younger daughter will say, “Stop body shaming that person.” And you could just be saying, “She’s tall.”

And if you do say the wrong thing, they’re going to correct you immediately. And eventually, a parent grows up and learns a few things from their kids. Like, I’ve learned to talk differently and just notice when I am cringey and awful.

Growing up in the ’80s, everyone was just insanely body-focused and looks-focused and sexist and just the worst. … I do think my kids have a much more flexible sense of what’s interesting, what’s valid, what’s beautiful, what’s unique. They’re much more playful and creative around aesthetics than I think we were.

One thing I was really struck over and over with was how often you and Bill take each other’s sides — or how you find a way to take each other’s side, even if you aren’t there to begin with. I mean, especially Bill, but both of you. What lessons about relationships and how marriages work do you think your kids are learning from being a part of yours?

Bill and I, in some ways, have matching insecurities and fears and weaknesses. So, in some ways we take each other’s side partially because we get into conflicts where it’s the only way out. We naturally actually agree on a lot of things, so that’s not a source of conflict that often. But we are both weak, petty, defensive people in our different ways. And so, we had to learn how to see each other’s perspectives just as a means of survival, I think. And I am not shy about giving my reasons for things.

I think that my kids have learned that it’s normal to be an intense, anxious, emotional person, which is good because they both, sadly for them, have some of our same traits. Not just from growing up with us — they’re wired similarly to us, I think. But they witness us managing to find each other again and again through honesty and through sometimes awkward and sometimes embarrassingly honest and sometimes vulnerable conversations.

There’s a chapter in Foreverland in which you list all the things that you do in order to keep the family circus afloat during a vacation to Australia, and one of your jobs is “tolerating personal slights” from your oldest daughter. I really felt that! It’s hard to raise a daughter, having been one. Are your daughters as mean to you as you were to your mom? Were you mean? I’m assuming you were.

I mean, yeah. I remember saying to my mom, “Oh my god, that’s so cheesy.” Over and over again. Everything she did was cheesy.

And my kids are like that, too. It’s all cringey now instead of cheesy, but same thing. I usually laugh it off. I know that part of my function is to serve as an example of what you don’t want to become. I mean, that’s your function as a parent of a teenager. Which is perfectly normal and valid.

In the cheerleading chapter, you describe your mixed feelings about your daughter wanting to follow in your footsteps with that particular sexist, yet thrilling activity. I really related to that. And I wondered, certainly not for the first time, why I took my daughter to ballet class, when I had such a fraught relationship with ballet my whole childhood. Why did I do that? Why do we do that?

Well, I think that there are ways that we remember what felt powerful and what felt empowering and freeing and fun, and what gave you a swagger in your step when you were younger. For me, the difference in how I encountered myself from before I was a cheerleader to after I was a cheerleader was massive.

My older daughter always loved princess stuff. Loved, loved, loved. And that is, obviously, just how some kids are. I was determined not to have any dresses, any Barbies. I didn’t want any gendered bullshit in my house. I just wanted the most gender-neutral stuff possible, but she immediately glommed onto everything princess.

For me, getting over the just constant prejudice that the world brings to your door as a woman past 40 relied on knowing that I cared and knowing that I deeply valued feeling like my words mattered. And that I had a place in any room. And I had something to say.

So, the thing is, you honor your kids’ desires and by the time they’re fucking teenagers and they’re like, “I want to be a cheerleader,” … I mean. I said to her, “Here are my experiences in cheerleading. In some ways you’ve got to admit it’s kind of sexist, and you’re on the sidelines for blah, blah, blah. But you do get to dance! And I do remember feeling kind of important because I was a cheerleader and that was nice.” And I also was so boy crazy. And it helps to wear a little skirt. When you’re boy crazy, wearing a skirt is good.

It’s so good.

It’s sort of like a vision quest! You just tell them your things and honor what they want and you don’t stand in the way. You don’t say, “No, you shall not.” I mean, if you want to reinforce it, you stand in the way of it.

I mean, I like to think that I’m modeling an extremely feminist way of life to such an extent that anything that felt insidiously, corrosively anti-feminist, my kids would be aware of it.

In another section, you write about looking in the mirror and seeing someone who feels, you say, “creepily really confident in herself,” even though she’s officially past her prime. And reading that chapter, in my head, I actually thought, Wait, we can do that? I don’t know why it’s still so astonishing to me, moving through the world as a woman in my 40s… but the messages that I receive on the daily are so contrary to that. And I wonder, will our daughters feel differently when they’re our age?

For me, getting over the just constant prejudice that the world brings to your door as a woman past 40 relied on knowing that I cared and knowing that I deeply valued feeling like my words mattered. And that I had a place in any room. And I had something to say.

It’s not so much that I expect to go to a hipster party and be cool. It’s not that. But it is a feeling of, I am cool. Cool is a bad word, but what I have to give does matter and it is valuable, and I’m going to hit the road with it and I’m not going to let my shape or my style prevent me from behaving in confident ways in public that are going to turn people off because I’m 51 years old. I mean, it turns people off to see a woman “of a certain age” acting like she’s not actively decomposing in front of your eyes.

Yes. Embarrassingly decomposing in the corner.

Once you understand what you value, then you start to say, “I am not going to accept some shitty story that the world tells about me. I’m going to find ways to subvert these messages.”

I just think women who are past 40 need to enjoy. And I don’t like talking even about the age of it. Because I think that you start to anticipate that you’re not going to matter in your fucking 20s.

Yes.

So, it holds you back at every age. And when you see it happen to older women — if you’re young, or ageist because you’ve been told to fear getting older — you feel disgusted with how older women do things, because you’re like, “Oh, look, she’s doing it wrong simply because she’s older.”

And it’s like, Oh, I have to battle that in myself along with everything else. I have to reject these weird internalized misogynistic ways that I just see other women. I have to change my windshield completely. I need new filters.

And once you get the new filters, life is just so much more fun and better. A younger person might say, “Oh, whatever.” A younger version of yourself might say, “Oh, God. You’re becoming one of those weird, old women who talk about how great they are and show off.” But in order to update other people’s notions, you have to actually be what you want to see in the world, obviously.

It is hard because the thing is, people you know, your intimates will frown on it. You put on red lipstick and some people you know will say, “Amazing.” And others will say, “The fuck are you doing?”

This interview has been condensed and edited.

This article was originally published on