she-hulk solidarity

American Mom Rage Could Fill A Book & Now It Has

“I know as the person who wrote this book, I’m supposed to say, ‘I never yell at my family anymore.’ But I don’t think that’s realistic. It’s also not true.”

Like many humans during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, I yelled a lot. I was tired, frustrated, a little hopeless, a lot desperate. But I was also something more than that. I went on what I called “rage walks,” giving my husband a simple nonverbal signal, after which I would fling myself out of the back door, headphones in, girl-punk soundtrack ON. I would get in my car, parked in the driveway, and scream so loud I startled the neighbors. I was often rough with my children, then 2 and 4. I met my son’s physical aggression with the grounded “I can’t let you hurt me” mantras I had, like a good mother, been trained to repeat. But underneath it was a slightly terrifying, unhinged quality, dying to get out (and sometimes succeeding).

I was so mad that I sometimes felt overtaken, Hulk-style, coming to after the fact, as if I had blacked out for a moment in my anger.

Even when much of my child care returned, when I began getting the social connection and intellectual stimulation I needed to construct some semblance of a healthy baseline, the rage continued. I knew from talking to other mom friends that not everyone experienced it at this level. We were all fed up, of course. We were all exhausted. And our children, to a one, were often quite annoying. But when I looked for understanding, or regaled my friends with a story about my rage, sometimes I would be met with a vacant look or a polite nod. It wasn't everyone, I accepted. But I knew it couldn't just be me.

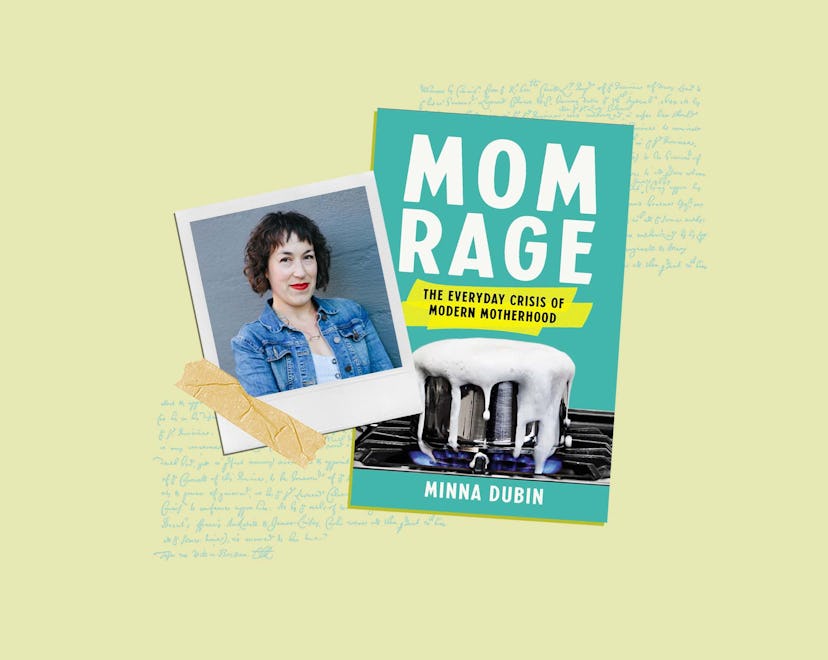

It wasn't. In 2019, long before the lockdown that kicked everyone's standard maternal rage up a few notches, Minna Dubin wrote an essay in the New York Times, called “The Rage Mothers Don’t Talk About,” that struck a chord with readers (and later, with me). Dubin’s confession of her own rage — and the shame that accompanied it — was such a combination of revolutionary and perfectly ordinary that it went viral, and it was clear to Dubin, and to her publisher, Seal Press, that there was demand for more. The result is Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis of Modern Motherhood, and it extends Dubin’s previous work — work that is essential and often overlooked — of making mothers feel seen, warts and all.

In the book, Dubin explores the concept of maternal rage, first through her own vulnerable story, and then through cultural and sociopolitical analysis. She also, to great effect, adds the voices of a truly diverse range of mothers to her own upper-middle-class, white and Jewish, San Francisco Bay Area voice. These mothers, despite vastly different circumstances, describe their experiences of rage with eerie similarity.

Though Dubin helps us think through ways to make our rage more tolerable and less harmful, and takes such harm seriously, she doesn't point fingers at angry mothers, even the ones who do things with their rage that might in fact be quite scary for their children. Instead, she deftly describes the larger forces that make motherhood, particularly in America, so damn infuriating.

As I was intently reading Mom Rage on a long flight, another mother leaned over to ask me, somewhat sheepishly, what it was about. “It’s about how all kinds of moms experience uncontrollable rage, directed at their kids, that is really related to how little our society gives a sh*t about moms,” I told her. “Oh!” she replied, her face a mixture of excitement and satisfaction, “I literally talk about that every day!” I had the chance to sit down and talk to Dubin about her own rage journey, her book, and why so many mothers recognize themselves in its pages.

What was the response to your original NYT article? Why did it make you feel compelled to write a book about mom rage?

I received hundreds of messages from mothers from around the world. The emails felt like an immense wave of grief being released. The mothers had been holding so much self-hatred and fear that they were the worst mothers in the world. I think the essay helped mothers forgive themselves just a little bit for what they’d been sure was a personal deficiency.

What these mothers didn’t know is that their messages provided me with the same relief. When I published that piece, I didn’t realize I wasn’t alone in my experience of mom rage. And I definitely didn’t realize my rage stemmed from systemic forces of oppression that set modern motherhood up to be an infuriating and disempowering experience. I wrote Mom Rage because it was clear to me that mothers, including myself, needed information on what mom rage is, why we are feeling it, and what we can do about it. And more than anything I wanted to continue offering moms that sense of relief and permission to give themselves compassion.

Why is it so important that moms (and allies) understand where this rage is coming from?

If we have no sociopolitical context for mom rage, then all we have is the superficial picture of an enraged mother. We need to understand mom rage so we can shift from blaming and shaming mothers (for our warranted response to an untenable situation) to holding society and fathers accountable for not taking care of mothers and families. Understanding mom rage is the first step towards creating a happier motherhood that holds the wellness of mothers as a top priority.

Did anything surprise you in your exploration of mom rage?

I was surprised when I discovered, through interviews with mothers, that mom rage can be internalized. I’m such a loud person, and I naturally externalize all my emotions, so it hadn’t occurred to me that there are lots of mothers out there experiencing mom rage without yelling and stomping! Many are taking out their rage on themselves through self-harm and substance abuse. I am so grateful to the mothers who let me interview them for this book. Their stories showed me what needed to be written.

What do you wish you’d known about mom rage before you became a mom? Should we be giving this book at baby showers?

I wish I’d known it was common, that it wasn’t my fault, and that I was a good mother and person regardless. If I’d known all those things, maybe I wouldn’t have been so ashamed and I would have allowed myself to get curious about my anger years earlier.

Baby showers are all about the arrival of the new baby, not the arrival of the new mother. I tell a story in the book about how I give moms an economy-sized bottle of laxatives at baby showers because even though it’s not a registry item, it’s the real support postpartum moms need. I hope I’m not comparing my book to laxatives(!), but in a similar vein, this book is a true support for mothers. It should definitely be a gift at baby showers.

Where are you on your journey with mom rage now?

I know as the person who wrote this book, I’m supposed to say, “I never yell at my family anymore.” But I don’t think that’s realistic. It’s also not true. I can say that I’m more mindful and aware of my rage. I’m much quicker to reach out to my mom friends when I feel despair that I parented badly. I’ve gotten good at repair. The book has helped open up communication about mom rage between my husband and me. It’s been healing to have him read it and talk to me about different sections. I think all people who love someone with mom rage should read this book.

If you could change one thing to support moms, what would it be?

It would be the implementation of professionalized universal day care and preschool for all parents. If we professionalize it, then men will want to do it, wages will go up, staff turnover will decrease, quality will go up, and care work will start to be seen as actual work deserving of respect and a host of benefits like sick days and health insurance. It would set a precedent for other care industries, like elder care, nannies, house cleaners, and in-home aides for sick and disabled people. The unpaid care work of mothers is tied up with the underpaid care work sector, which is mostly done by women of color and immigrants. We are all suffering from the devaluation of care work. If we could change that, it would revolutionize the way we look at care work. It could degender it. It might normalize fathers as primary caregivers. Everything would change, maybe even our rage.

Minna Dubin’s new book Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis Of Motherhood is available now.

This article was originally published on