Life

Removing Fallopian Tubes Might Help Prevent Ovarian Cancer

In their lifetime, a person with a uterus and ovaries has a 1 in 75 chance of developing ovarian cancer. Of those who do, 1 in 100 will die from the invasive, often difficult to detect, cancer. Researchers have been trying for decades to learn more about, and prevent, the reproductive cancer and a new study shows promise. It turns out that removing fallopian tubes might help prevent ovarian cancer, because the organs might play a unique role in the cancer's development.

According to the American Cancer Society estimates, around 22,280 new cases of ovarian cancer will be diagnosed in the U.S. this year. The cancer is often difficult to diagnose because the symptoms can be vague, or even non-existent, in the early stages of the disease. Unfortunately, that means that many who are diagnosed start treatment later rater than sooner, and that's one reason that the cancer claims so many lives each year. When ovarian cancer is found at the early, localized stage, the survival rate after five years is 94 percent. But only about 20 percent of ovarian cancers are found at this stage. Most ovarian cancers are diagnosed in women between the ages of 55 to 64, but they can also occur in younger people.

Treatment for ovarian and other reproductive cancers can include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, and surgery. Most often, it's a combination of all of those things, and the extent of treatment will depend on how aggressive the cancer is. Sometimes, especially if the patient is done having children or has gone through menopause, a hysterectomy will be done to remove the ovaries, uterus, and cervix, according to the American Cancer Society. It's not uncommon for another important part of the female reproductive tract, the fallopian tubes, to be left alone. But new research indicates that they may be the key to figuring out where, and how, ovarian cancer begins.

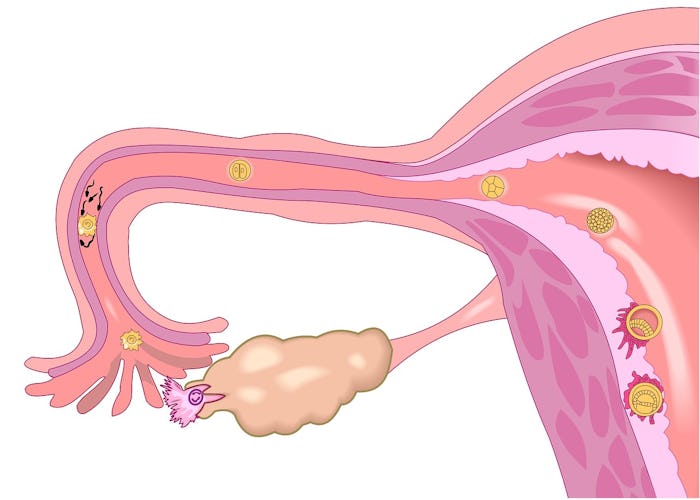

The fallopian tubes connect the ovary to the uterus, and that's how an egg released by the ovary gets into the uterus where it has the potential to be fertilized by sperm. It's was believed for a long time that, when a hysterectomy is performed, for a number of reasons, the tubes didn't need to be removed unless they were obviously damaged or diseased. But several studies in the last few years indicates that the fallopian tubes might actually play a very important role in the development of ovarian cancer — and therefore, they should be removed along with all the other reproductive organs.

Complete removal of all the reproductive organs has been standard practice for patients who have BRCA 1/2 mutations (like Angelina Jolie), but it has its own risks to consider, which is why doctors have been hesitant to recommend it more broadly. But this new research shows that removing the fallopian tubes during a hysterectomy didn't overly complicate the surgery and cause complications for patients, and post-surgery patients seemed to do just as well as those who had not had fallopian tubes removed. And, in fact, those who had their fallopian tubes removed may have better longterm outcomes because their risk for reproductive cancers has been greatly reduced by removing the organs from which they arise.

There could also be a benefit for women who are at-risk because of genetic mutation, but are still relatively young and aren't ready to endure the side effects of having their ovaries removed (like early menopause). The research indicates that removing the fallopian tubes might be a good interim step for younger, at-risk patients, but it's not yet understood just how much it would reduce the risk. Another common, and less invasive, preventative measure is the use of oral contraceptives. Research has shown that women who use birth control pills for five or more years have 50 percent lower risk of developing ovarian cancer compared to those who have never taken the pill.

Still, doctors need to discuss the risks and benefits with each patient individually. Additional research still needs to be completed, but these latest findings bring up some really interesting theories. They also serve as a reminder of the often quiet danger of ovarian cancer, and should further motivate women to listen to their bodies when something isn't right and empower them to make informed decisions about their health.