Exclusive

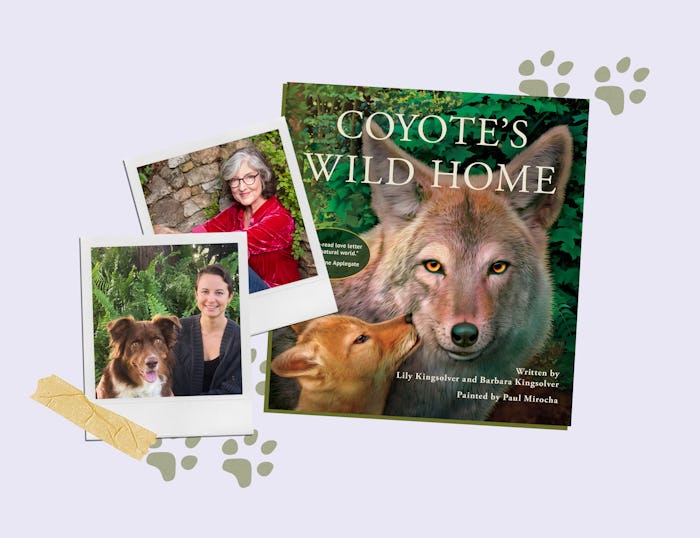

Barbara Kingsolver & Daughter Lily Used Their Wild Childhoods As Inspo For New Children's Book

The mother and daughter thought it was high time we saw coyotes as “good guys.”

One of Barbara Kingsolver’s favorite aspects of childhood is how infrequently adults appear in her memories. “I just spent as much time as possible outdoors,” she tells Romper by Zoom from her home in Virginia. “It was so formative for me that it was important to me to raise my kids as similarly as possible.” She pauses. “They probably have more of me in their memory than I do of my parents because they were a bit more supervised, but one of their favorite games was ‘Orphans in the Woods.’ They got rid of the parents pronto.”

The Pulitzer Prize-winner youngest daughter’s, Lily, also on the call from her home in Florida where she is working toward a master’s degree in environmental education, is clearly grateful for her wild childhood, developmentally normal fantasies of being orphaned notwithstanding. “Growing up in these mountains has shaped everything about me,” she says. And it started, according to her mother, from her earliest days, not just the camping trip taken when Lily was weeks old, but any time either of her daughters, Lily or elder Camille, got fussy.

“It would always calm them to take them outdoors, to get them under trees so they could look up at the sky and see that pattern of leaves and sky,” says Barbara, author of The Poisonwood Bible and Demon Copperhead. “It was almost magical in the way that it would calm them, probably because it was also calming me!”

The pair were recently able to share their reverence for the natural world in a new children’s book, Coyote’s Wild Home, which parallels a girl’s first camping trip with her grandfather to a coyote pup’s first hunt. I sat down to talk about the pair’s book (Lily’s first), the joys of an Appalachian childhood, and the importance of encouraging kids to engage with nature.

I want to start by asking about the genesis of Coyote’s Wild Home. How did this come about?

BK: The publisher, Gryphon Press, have a series of books about animals that engage with children and their parents about the lives of different animals. They had the idea of inviting me to add to this series by writing a children’s picture book about coyotes. And I thought, “What a great idea; I can’t do it.” I had already written the letter saying, “I love this idea but I cannot write children’s books. I’ve tried. In my long career I’ve tried actually several times over and over again. It’s just not a skill I have.”

Enter Lily. Lily came over to the house that day and saw sitting on my kitchen table this beautiful book [Warbler’s Journey, a previous book in the series] and this invitation letter and my response, and she said, “Why wouldn’t you do this?” I said, “Because I have no idea how to get the complicated natural history of coyotes into a narrative for 8-year-olds. I don’t see how that’s possible.” And Lily said right there and then at my kitchen table, “Well, what about this?” And she just rolled out the story and I said, “You should write this book.”

LK: I was so excited to be invited to do this with mom and so excited that Gryphon Press were willing to let me come on board. It was also right before I moved away from home and started grad school, and so it was a really cool way to connect because I wasn’t living next door anymore. I couldn’t just drive over and have a chat. So it was a good excuse to call mom on a Wednesday. “We have to talk about what we’re going to do on page five.”

BK: It would never have happened without Lily. It’s so serendipitous that she walked into the kitchen at that moment because an hour later I would’ve already sent that letter saying, “No, thank you.”

LK: Mom is being very humble about all this. She can do pretty much whatever she sets her mind to. As you know, she does have a Pulitzer prize-winning knack for dialogue and poetry...

BK: No, I could not have written this book, not in a million years.

I noticed something in Coyote’s Wild Home that I don’t often see in nature books for kids. So often humans in an animal context are either the noble protectors, masters of the land who owe it to animals to help them, or we’re invasive predators and exploiters of animals. But you present humans very neutrally. And it’s not so much that you’re humanizing the coyotes as you are just observing what coyotes and humans have in common. What made you want to approach the material like that?

BK: That was really natural for us because that’s how we feel. We’re both trained as biologists; we understand ourselves as animals. So it wasn’t a stretch for us to tell a story of animals and animals.

LK: I think really central to all of this was the idea of empathy for us and the idea of connecting to these animals in... Like you said, not necessarily “we need to save them” or “they’re disappearing.” Because we know about child psychology that before around the age of 6, they can’t really wrap their minds around those issues. And even when they can wrap their minds around those issues, they’re too overwhelming and too scary to tell a lot 6-year-old, “It’s up to you.” So the first step is just to cultivate this environmental sensitivity to position kids in the natural world, to show them that it’s not necessarily the big bad wolf out in the woods. It’s not this scary other world. It’s a place where you can go, and you can see these beautiful things and appreciate it and see yourself in this food web in the context of a larger ecosystem.

Why do you think coyotes are so misunderstood?

BK: That is exactly why we felt like we had to take this opportunity. To try to turn around this baggage of — I think it extends to predators in general — the big bad wolf. The grandpa in this story who’s talking to his granddaughter when she hears coyotes and she’s afraid that’s a pretty conditioned, but also not unsurprising, response. She runs to him, and he gives her a hug and he says, “We don’t need to be afraid of them. They’re good guys.” One thing we wanted to talk about in the book is why predators are the good guys, how important are they.

LK: There’s so much negative PR, especially about the edge species that are really adaptive like coyotes, raccoons, and bears. Animals that are coming into our space. It’s a little scary, but we’ve already come into their space quite a lot. Bears need to knock over bird feeders and eat. This is a scary thing when you see it, but it’s because we’ve given them no other option. I think that’s what we were really gently trying to put into this book.

I have this memory of being probably around 7 when we moved to Virginia. I was reading inside one day and I heard one of my beloved chickens outside making a ruckus. So I ran out, of course, and this chicken Saffron, my beloved rooster, was in the mouth of a coyote.

Oh my God.

LK: I looked at this coyote and the coyote looked at me and we had this moment of, “Neither one of us thought we were going to get this far.” And then the coyote dropped the chicken and ran away because I, at 7, was terrifying to this adult coyote. I had never been a formidable person. I was definitely not formidable at 7. It was a real moment of seeing that thing that we tell kids about — it’s more afraid of you than you are of it. It’s easy to say that, but I really realized that in that moment that like, “Wow, I just faced off with a coyote and I won. I scared it off.” I was experiencing the reality of “They’re more afraid of you than you are of them.”

Paul Mirocha’s illustrations in this book are gorgeous. Was there anything it was really important for you that he include? Is there anything in particular he brought into the pictures that stands out to you?

LK: Oh, he’s amazing. He pays attention to the species and every little plant, every little leaf. He’s a scientist. He does a scientific illustration and he really brought that to the book in a way that was so beautiful. He's been mom's friends since before I was born.

BK: Paul Mirocha and I go way back. When I was a baby reporter he was a baby artist and we did projects together. We’ve worked together for more than 30 years. When Emilie [Buchwald, founder and co-publisher of Gryphon Press] asked us if we had a favorite illustrator, we said, “Yes, we do.” And she said, “Oh, Paul Mirocha, he’s really wonderful, but I don’t know if we can get him.” And I said, “Let me try.”

We said [to him], “First thing, you need to come and see this place because this is where the book is set. So he came and actually stayed with us for a week, and we took him to all of our favorite places and he photographed them. Lily had already moved to Florida by that time, so she was sending us GPS coordinates. So many of these images are very familiar to us. It was really fun to see, not just our words, our story come to life, but our farm come to life, because we certainly do have coyotes here. They’re all around us.

You were both raised primarily in Appalachia — Barbara in Kentucky and Lily in Virginia — how do you think that affects how you see the world?

LK: Oh, man. It’s just everything. Growing up in Appalachia changed the way I see the world forever. I think we are all getting that from wherever we are, no matter how much nature is there. Because there’s nature everywhere, there’s a tree somewhere in everyone’s life. Even if it’s one tree, that can be a kid’s one tree, and that can be their connection. I think where you’re situated in the world changes so much of how you see things and what you do. It’s very easy to be out of touch with your ecosystem, but it’s also very easy to learn about that ecosystem and change your life to fit in with it.

BK: If you didn’t have the great fortune of being a wild child raised outside, I think Lily’s point is so important that we can shift this cycle. We can be more interested, we can help our children have more comfort and a better familiarity and positive feeling about nature than we did, just by checking our responses. Instead of saying “ew” when your child brings you a bug, take a deep breath and say, “That is so interesting. How many legs does it have?” And sometimes it might be an effort. Just have some consciousness of that.

So Lily, I’m a writer and my mom is also a novelist. I initially didn’t want to be a writer because it’s like, "Oh, that’s mom’s thing." Did you ever not want to be a writer or did you have an inkling you might want to at some point?

LK: I think it just happened. I never intended to, if mom hadn’t invited me to write this, I don’t think I ever would’ve come up with that myself. But then as soon as I was doing it, I was like, “Yeah, this is really fun. I want this.” I think it all just happened.

BK: Well, I’m going to disagree with Lily. I have known since Lily was probably 2 or 3, and I’m not kidding, that she was going to be a writer in some way. I think some people just love words, and Lily is one of those people. She started writing poetry when she was young and still writes poetry, has written beautiful poetry. I think Lily has found her niche in the family as the writer. This is not going to be Lily’s last children’s book, I promise you.

Coyote’s Wild Home, by Lily Kingsolver and Barbara Kingsolver, illustrated by Paul Mirocha, is available now wherever books are sold.