Books

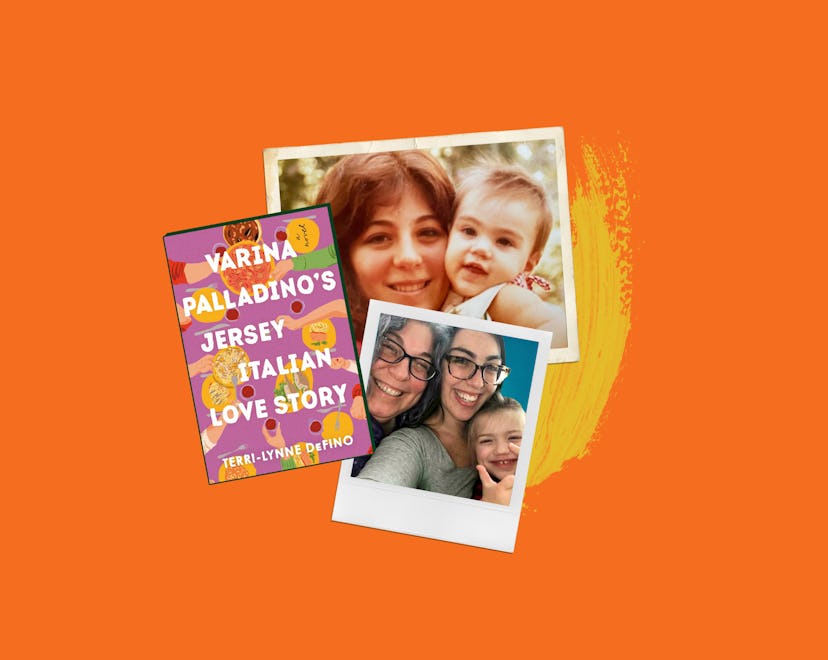

My Mom Wrote A Book About Motherhood & Identity — & It’s Familiar

In Varina Palladino’s Jersey Italian Love Story, my mother Terri-Lynne DeFino explores what it means to an entire family when a mother chooses herself.

As I interview my mom, Terri-Lynne DeFino, about her new book Varina Palladino’s Jersey Italian Love Story, she keeps trying to feed me. “That’s a good point, and I’m thinking…” she interrupts her train of thought. “Do you want some of my bisque? Here, make sure you get some lobster on the spoon… did you get lobster? How about the kale salad? It’s such a Jamie salad, you’ll love it.”

We’re at my mom’s favorite restaurant, a popular Italian spot minutes from my house. She and my dad have come so often that they’re friends with the owner and chef; Tony often comes out of the kitchen to chat. They know the entire waitstaff by name, and they’ll ask about their kids during water refills. “I’m a family-maker,” my mom says at one point in our conversation. “Everywhere I go I create a family.”

I say all this because my mom could be describing (and personifying) her titular character.

Varina Palladino is busy. From the family business (a locally beloved Italian grocery store she started with her late husband) to the emotional well-being of her children (two workaholic sons and an emotionally complicated daughter) to her 92-year-old mother, everything, it seems, depends on her to manage it.

Varina also has a habit (very much like my mother) of taking in “strays,” most notably Paulie, her daughter’s childhood best friend who was deemed a fanook by his own family after coming out. (“Fanook: a derogatory term for homosexual,” the book explains. Each chapter begins with a brief lesson on Jersey Italian slang. Some words people might be familiar with — capeesh — others they almost certainly aren’t — schiatanumgorp… don’t worry, they’re also spelled out phonetically.)

Shortly after we meet Varina, the 70-year-old truly grasps what defining herself by caregiving has meant in her life: she really doesn’t have one to speak of… and that’s no longer acceptable.

“Whether women have a career or are homemakers or whatever they are, I think there’s this thought that they have to always be the one taking care of everybody,” my mom says. “And there comes a time where you say, ‘I’ve got to take care of me.’ There’s a lot of me in Varina.”

There’s a lot of Varina in my mom, but they’re not the same person.

For the first almost six years of my life, we lived in a basement apartment in my grandparents’ house. For about half that time, by the time my mom was 21, she was widowed with two children. The apartment was tiny. Open the front door and you’re within feet of the kitchen table. To the left was the bedroom I shared with my brother. A few steps straight through the kitchen was the living room, which doubled as my mom’s room, though visitors wouldn’t realize that. Most of her personal items, including her bed (a pull-out couch), were tucked away out of sight with one exception: her writing desk and her typewriter.

Looking back, this feels like a metaphor. Like, if it were in a novel the editor would say, “OK, let’s calm this down a bit.”

Writing was always a priority… though for the first decade or so of my life it was more symbolic or hypothetical. By virtue of her eventual gaggle of children (she remarried and there were four of us by the time I was 9), writing was something she fit in when she could. But when she did, it was sacred and I did not interrupt… I mean, I was a kid so I’m sure I did, but my memory of her writing in those years carries with it a strong sense of “Do not disturb.”

In 1996, my youngest sibling started kindergarten and suddenly my mom found herself with three hours a day, every day, to herself. First grade — and six hours a day — were visible on the horizon.

“I had to decide, do I want to go out and get a paying job of some kind, or do I want to really focus on the writing and make it work,” she tells me. “This is what I wanted my whole life; I wanted to be a writer. And I knew it was going to take a lot of hard work and a lot of effort that was never going to see a penny.”

She chose herself. From there on out, she averaged a book a year, every year.

“Those first years were the years I taught myself how to write. Lots of novels that shall never see the light of day,” she says sheepishly. “I never went to college, but I wrote consistently every single day.”

I remember coming home every day from high school and looking up and seeing my mother at her desk in her second-floor bedroom, like a witch in a tower typing away, conjuring words, creating worlds.

At the time, it was something I took for granted. Of course she spent six hours a day writing — she’d shown us for years how important it was to her. What else would she do? It wasn’t until later that I understand my image of her as a word witch in a tower was more accurate than I realized. Her passion, her commitment, her discipline, feel miraculous to me. To have grown up seeing that as normal has affected me in ways I’m still, happily, figuring out, both as a writer and a mom myself.

There’s a lot in Jersey Italian Love Story that’s familiar beyond Varina and the colorful, highly specific dialect. Sometimes it’s little things: my mom’s purple hair (though on her book jacket picture it’s pink and at lunch she rolls up with blue), the antique Victrola that’s been in the family for 100 years (currently in my living room), or the fact that my mom was watching a lot of home renovation shows while writing the book (there was a time where she wouldn’t come into my house without musing over which walls could come down).

Some things are bigger. I see family members in each character. Elements of my aunt, my brother, and my sister can be seen in a single character. I see conversations I’ve had with my own grandmother about racism. I see my mother’s struggles with my youngest brother in Varina’s struggles with her daughter Donatella, whose best intentions don’t prevent her from making the worst decisions.

I also see my mom’s greatest gift to me in Varina’s journey throughout the book: unabashedly being her own person, an individual who loved us dearly, but who existed beyond me and my siblings and the things she did for other people.

“I always tried to set that example for you kids, especially you and your sister,” she says after urging me take more salad. “I tried when you were growing up to make sure that you always knew I wasn't just mom, I was also other things.”

She hopes it’s a lesson other readers can find in the novel as well.

“Women having babies now, don't fall into the same old traps that we did,” she says. “Don't wait until you're 50-something years old to say, ‘Okay, what about me?’ Show your children you're not just an extension of them. As for adult children: let go. It is a gift to them and it's a gift to yourself.”

Gift received, mom. Though let it be known to all that she vehemently refused to let me pay or even split the bill, because God forbid she doesn’t feed me…

Varina Palladino’s Jersey Italian Love Story is available now wherever books are sold.

This article was originally published on