Life

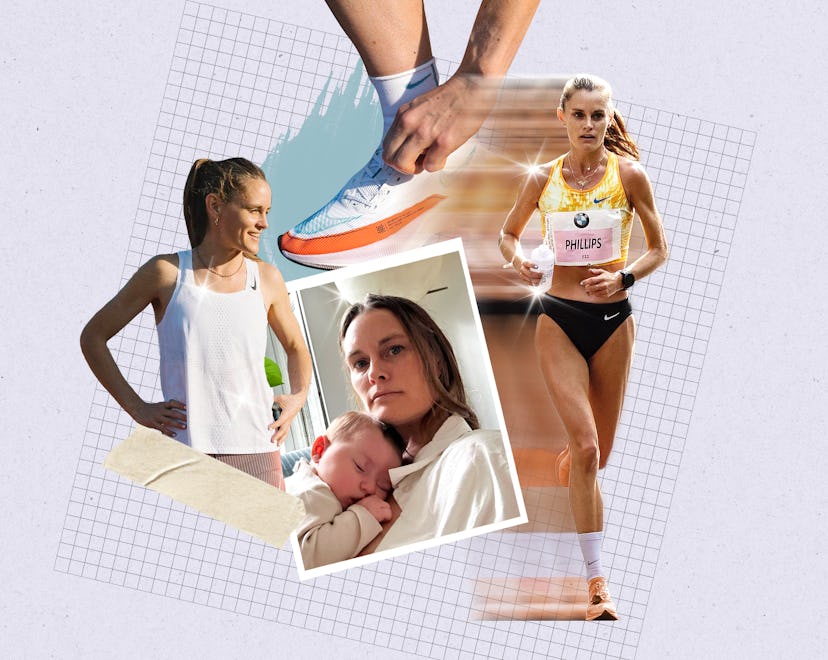

The Marathon Runner Who Got Real About Her Birth Injury

For Caitlin Phillips, giving up running entirely would feel a lot like giving up her former self.

After having her first baby, Caitlin Phillips intended to be generous with herself, and take a long recovery period before returning to running. You know — like, three whole weeks, or maybe even four.

“I thought four weeks would be me being patient, honest to God,” said Phillips, 41, who is a three-time U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials qualifier. She’s now five months postpartum, living in Brooklyn, and she is running, but not like she used to. This is a woman who used to blast through 100 miles a week while working full-time, who finished in the top 20 three years in a row at the competitive Berlin Marathon, and who was so determined to return to running in 2009 after a post-college hiatus that she ran 2 miles around a track in her bare feet. (She didn’t own running shoes at the time; she couldn’t afford them on her minimum-wage income at a photo studio.) These days, her body allows her to run every other day for 10 minutes at a time, alternating between one minute running and one minute walking.

“If I run two days in a row, it’s just — no,” said Phillips, who has been dealing with pelvic floor pain ever since giving birth in November. “So yeah, I’m losing my mind a little bit.”

We got together for a walk on a recent sunny morning in Prospect Park, where she used to run the bulk of those 100-mile training weeks. We hadn’t met before, but I instantly clocked her by the Bandit socks sticking out of her Blundstones. Bandit, for the uninitiated, is a newish, stylish, if-you-know-you-know-ish running apparel brand, based out of Brooklyn and favored by fast runners as well as people like me, who are not particularly fast but would like to dress the part.

In the running world, the fast runners tend to be the cool runners, the trendsetting runners, the runners who influence the rest of us into buying $285 racing shoes we probably don’t need. Usually, “runner cool” does not translate into real-world cool — too much striving neuroticism for that. But Phillips is cool and funny, and she speaks in an unhurried, low tone, sometimes slipping into the tiniest hint of vocal fry. She is from Cleveland, but she gives Californian.

Like many runners who are fast, but not fast enough to quit their day jobs, she works full time. Since 2017, Phillips has been the executive art director for MAC Cosmetics, where she hires photographers and oversees photo shoots. (She’s currently on maternity leave.) She has the petite build of many competitive distance runners, and when we meet at the park, her long brown hair is half-down, half-up in the kind of thrown-together messy bun it secretly takes me multiple tries to achieve. On her, I believed in the thrown-togetherness.

With Phillips is baby Tava, her 5-month-old daughter, hanging out in an Artipoppe carrier. Pre-baby, she would run in the park four or five times a week, usually with a pack of friends around her. Now, she gets here once every other week, tops — just for a walk, just her and the baby. Is it kind of nice, I ask, to get to take in such a familiar place at a slower pace?

“It’s definitely nice,” she says, as a runner passes us. “It’s also definitely pangs of, ‘God, I wish I could be RUNNING!’”

She is walking, not running, because of what she has come to call her “birth injury,” a mysterious, persistent posterior pelvic floor pain — a literal pain in her ass, in other words — from which no medical professional has been able to help her heal. (She’s so far visited four physical therapists, a midwife, a functional health doctor, and a “doctor-doctor”; she’s hoping to see another specialist in Washington, D.C., this spring.) And the activity that exacerbates it the most, much to her frustration, is running.

Her relationship to running was always going to change; motherhood changes your relationship to practically everything in your life, including, if you’re an athlete, your sport. Though if you read running media lately (what — you don’t?), you might think that change only happens for the better.

On March 2, two days before her son’s first birthday, Elle St. Pierre won gold in the 3,000 meters at the World Indoor Championships, beating the world record holder. “Having a baby has only made me stronger,” she told Runner’s World. In February, one of the big stories leading up to the Olympic Marathon Trials was the mom angle: Nearly three dozen women (out of 160 total) set to line up that day were moms, and a few were under a year postpartum.

“No shade, no envy, that’s incredible, that’s great,” Phillips said. “And, I mean, I’m also not at the level that a lot of these moms are in the first place. … But I don’t know how these moms are just, like, breastfeeding and pumping and also crushing their PRs. Like — Jesus Christ!”

It is, on the one hand, a huge step forward for women in a sport that has been less than welcoming — if not downright hostile — to new and expecting mothers. In the past five years or so, a number of professional runners who are also moms have come forward to speak about poor treatment from their sponsors after getting pregnant.

“Getting pregnant is the kiss of death for a female athlete,” runner Phoebe Wright told the New York Times in 2019. “There’s no way I’d tell Nike if I were pregnant.” (Wright was sponsored by Nike from 2010 to 2016.) Another former Nike athlete, Kara Goucher, revealed in her memoir last year that the brand withheld a quarter of her $325,000 annual salary while she was pregnant. And though Molly Huddle eventually did manage to secure pay through her pregnancy while sponsored by Saucony, it took many years of hard negotiating.

Policies have improved in recent years. Nike, for instance, has instituted a maternity leave policy for its athletes, and last spring, Runners World published a piece about the resulting “elite runner baby boom” that followed these positive changes from sponsors.

That story was published when Phillips was in her second trimester, having already qualified for the next year’s Trials. She thought she would be there; she should have been one of those less-than-a-year-postpartum moms. Reading the coverage from home was harder than she expected. On Jan. 29, five days before the race, she posted two photos of herself to Instagram: an old one of her racing, and a new one with baby Tava sleeping on her chest. “While I fully expected to have my fair share of challenges, I didn’t quite anticipate that I’d still be having quite so many issues or be wondering if I’ll ever run again,” she wrote in a lengthy caption.

She got mostly supportive, positive responses, but there was one comment that annoyed the hell out of her. “It was like, ‘Well, you just have to reevaluate your relationship to running now that you have a baby,’” she said. To Phillips, this felt like someone telling her that her entire identity had to change now that she was a mom. “It felt like one of those, ‘Well, I just changed myself because I had babies!’” she said of the comment. “I’m like, ‘OK. Great for you.’”

Phillips doesn’t feel like a brand-new person and chafes at the suggestion that she should become one. Giving up running entirely, something a few health professionals have suggested, would feel a lot like giving up her former self. “I’ve had physical therapists tell me, ‘Well, you just need to reevaluate and make lifestyle changes’ — i.e., not do any high-impact exercise,” she said. “And I’m like, ‘OK, well, I’m frankly very annoyed by that idea.’”

So she isn’t a new person, and isn’t interested in becoming one. Still, there is a new … something … when it comes to running. A new outlook, at the very least, and new ambitions, too. Instead of being laser-focused on numbers, Phillips’ biggest running ambition at the moment is to feel good enough to be able to run with her friends again. “I miss my normal crew that I would meet up with every morning,” she said. “It’s just so nice to start your day that way, where you’re like — ‘OK, I’ve already had my friend therapy session.’” Eventually, she wants to introduce Tava to the sport she loves, too, logging some miles in the jogging stroller.

When she talks about what she wants next in running, she doesn’t mention PRs or goal races — she mentions the 20-something mile training run she did just before her Olympic Trials qualifying time of 2:35:03 at the California International Marathon in 2022. (She ran that race 10 days before the day she is pretty sure she conceived.) “I just keep thinking about that run,” she said. “I want to be able to lock into that feeling that I had that day.” No spectators, no starting gun, no competitors. Just her, by herself, on a beautiful day on a beautiful trail in the mountains, doing what she does best.