Tech

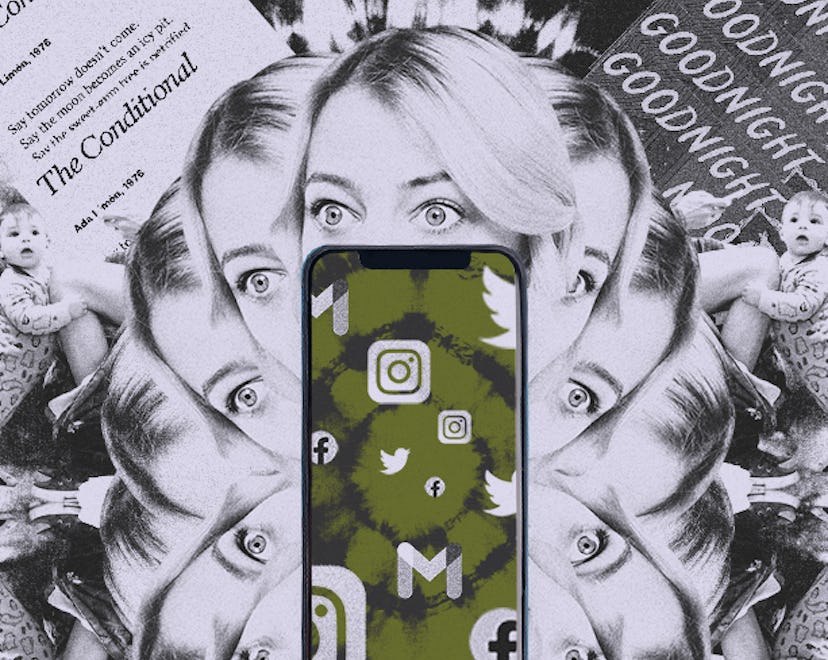

What If Our Phones Give Us Something Our Children Can't?

Getting rid of my phone would not make me fully present in my life, because I don’t entirely want to be.

My daughter, age 5, finds me in the bathroom, scrolling Instagram.

“What are you doing?” she asks. “You said you would play with me in a minute. It’s been a lot of minutes.”

“I’m doing some work things,” I say. “I’ll be there soon.”

She walks away, yelling over her shoulder, “It’s Unicorn Club Day, and you’re gonna miss it!”

I first tried to break away from my phone a couple of years ago. I deleted Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and Gmail after I wrenched myself out of a particularly long Instagram jag to take a picture. When I opened the camera, the screen was flipped, and I was startled by my own dead-eyed face. Disgust swirled in my stomach. I clicked my phone asleep and looked around, blinking, like I was taking in my surroundings for the first time. That image, the zombie version of myself, haunted me for the rest of the day.

All of the things that are supposed to happen when you cut your phone time happened. When I stopped looking into my phone and actually looked at my children, I noticed a faint scratch on my son’s nose — from what? That my daughter could form capital letters clearly on her own. Space opened up. Time. Quiet. I relearned how to sit and think again, how to get lost inside my own mind rather than mindlessly scanning images of others. I took pictures but I didn’t share them. This is my daughter drawing in her unicorn costume. This is my perfect greasy pizza. These are my husband’s blue, blue eyes, I said to myself.

Eyes linked to my screen, shoulders bunched, jaw set, my body forgets it is even a body. The pad of my pointer finger taps the tiny heart again and again.

Last year, I read a book called How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy by Jenny Odell, an artist and critic who had her own epiphany about her relationship with the second, digital life we all lead now. “A simple refusal motivates my argument: refusal to believe that the present time and place, and the people who are here with us, are somehow not enough,” she writes.

I share her conviction, but I struggle to maintain my own refusal.

One by one, each app came back like a lost cat mewling for milk. Instagram was banished for only one week, Twitter for two, Facebook and Gmail for two and a half.

Every few months, I would try again. Quit, and then invite them back in. It turned into a ritual, almost.

Then came March 2020. When my world contracted to the boundaries of my house, it became acceptable to think of my phone as a lifeline. I needed whatever solace my tiny screen could provide: Marco Polos and GIF texts with friends, Snapchats from my sister, and even the obsessive scroll, which confirmed that others were also struggling to make it through the fog of lockdown.

When quarantine temporarily unburdened me of my phone guilt, I found myself observing my phone’s effect on me the way yoga teachers tell you to, without judgment, without the next digital diet looming over me like a threat.

When I am looking into my phone, the husk of my body is here, but my presence is in another dimension. There, I shift and shimmer. I shed my old abilities and take on new ones — I leap from image to image, transforming each memory’s lighting with a click. Eyes linked to my screen, shoulders bunched, jaw set, my body forgets it is even a body. The pad of my pointer finger taps the tiny heart again and again.

Intermittent rewards are the most addictive, at least according to B.F. Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning. They are also the kind that fit particularly well into the continually interrupted life of parents of young children. If you are trying to get something done, Murphy’s Law of Parenting dictates that you will have to stop doing it every four minutes to serve someone else, and when you start again, you will not remember where you left off. You’re tired and frustrated, so you want a little hit of something good. You open your phone — no, you’re already on it, in the bathroom — and you follow the next notification anywhere but here.

My head turns like it once would have turned toward the sound of a bird or a child. My body feels a tidal pull.Where is my phone? Where is it?

At the park, I stare at my phone, occasionally making myself look up to see my kids — still there still there all good. It is hard to just watch my daughter make mud pies or to breathe deeply the midsummer air. My phone keeps calling me, pulling me toward its magnetic field — “just a second... I can look... just a second...” then minutes, minutes, minutes.

When my son falls and cries out for me, I rattle awake and rush to him, shoving my phone in my pocket. I feel a flicker of guilt. I want to be the mother who is present for her kids, who notices when they fall. But I also want to stay there, reading the Ada Limón poem, my mind in the space it used to go without telling anyone where it was going or when it would be back. What if my phone is not the distraction? What if it is my child who is distracting me from being present to other worlds? To myself?

Reading with my daughter is one of the only times I don’t have my phone with me. She crawls up on my lap, and elbows me in the head or presses too hard on my bad knee and I groan and wait for her to distribute her weight. I open the book, and we both shift and move into place until we’ve become one being. For the time I’m reading, I can usually focus on just this. But sometimes, I get a few pages in and realize I have no idea what the story I’ve been reading aloud animatedly is actually about. Why is this cat going to different houses for dinner again? I don’t know because I’ve been wondering if I have any new texts or emails.

My cortisol levels rise when I’m near my phone but not holding it—I’m alert, like a deer sensing another’s presence. My head turns like it once would have turned toward the sound of a bird or a child. My body feels a tidal pull. Where is my phone? Where is it?

I know that this is how the platforms and apps are designed to make me behave, and I know that they are not offered freely: If you’re not paying for the product, then advertisers are paying for it, so you are the product they're paying for (your data/attention/money et cetera). If I am the product, and my behavior is being changed imperceptibly in negative ways by interacting with this device, and records of my interactions are being sold all the time, and I don’t feel able to stop using it, then logically, I should get rid of it.

But I don’t want to.

Every time I quit, I also stage a small internal rebellion, enumerating the meaningful tasks I accomplish while I scroll myself numb. While I’m disengaging from my immediate environment and the humans physically present in it, I’m also staying informed about voting rights, responding to a student’s email, cheering my friend on her recent publication.

Besides, I don’t feel like a product when I’m sending my friend a message with @ghosthoney’s latest TikTok. I smile and bop my head a little. Don’t I need more of that in my life? More buoyancy and less grim-faced writing of emails — even if the algorithm is sharpening its blade with my every click?

I went back on Instagram again in late spring, after deleting the app yet again from my phone. My husband was visibly disappointed. Other than an annual check of his Facebook account on his birthday, he mostly uses his phone to call people. He said, “I just think there are so many better things to do with your time.”

I know that there are.

The other night when I was out with friends, I laughed so hard I cried. My glasses speckled with tears. I can’t remember what I was laughing about now, but I felt more alive and present in my body than I have in a long time. My phone was a powerless slab in my bag.

I want to be there, really there, when my children fall, without giving up the right to be in my own head, too. How do I do that?

If this were a movie, the final scene would feature me throwing my phone into the river, music swelling, while I walk away with the wind in my hair. But getting rid of my phone would not make me fully present in my life, because I don’t entirely want to be.

The truth is that I want to enjoy the benefits of my phone without the costs swallowing me whole. I want its numbing mental insulation when I’m too exhausted to be present but too needed to rest. It may be part of the ruse, but I believe that by reading the occasional poem on my phone, I can feed the parts of me that the demands of motherhood starve, so that maybe that version of me will still be standing when my kids are grown. I want to be there, really there, when my children fall, without giving up the right to be in my own head, too. How do I do that?

I was on my phone just now, and my son came over and placed a ladybug on my hand. I put my phone down and looked at it with him. At first, the ladybug was stunned. It hunched, frozen in its ruby shell, antennae vibrating slightly. Then it crawled across my skin and took off. Much farther than I thought it could.

Emily Mohn-Slate (she/her) is a poet, essayist, and teacher. She is the author of THE FALLS, winner of the 2019 New American Poetry Prize (New American Press, 2020) and FEED, winner of the 2018 Keystone Chapbook Prize (Seven Kitchens Press). Her poems and essays have appeared in AGNI, New Ohio Review,Racked,Muzzle Magazine, Tupelo Quarterly, The Adroit Journal, and elsewhere. She teaches high school English by day and poetry workshops by night for the Madwomen in the Attic at Carlow University. She lives with her family in Pittsburgh, PA and is probably trying to write while being interrupted to be in a puppet show or to find a purple marker.

This article was originally published on