Life

The Book That Helped My Son Rediscover Reading

Reading a book 200 times is a surefire way to find out whether you love it or want to throw its rhyming llama couplets into the diaper pail. Children's books especially do a tricky dance for an audience of squinty-eyed parents and wide-eyed tots: the best ones, like a syringe of infant-suspension Tylenol, have a little something for the parent at the end. These are the ones we are celebrating in This Book Belongs To — the books that send us back to the days of our own footed pajamas, and make us feel only half-exhausted when our tiny overlords ask to read them one more time.

My 10-year-old son wasn’t reading and I couldn’t figure out why. He’d grown up on books. His mom and I had read to him quite literally from the day we’d brought him home from the hospital. He’d once competed with his younger brother to see who could read the most books before bed.

Now in fifth grade, it had all ground to a halt. At night we sent him upstairs with his book — usually a hot new YA novel recommended by the school librarian. With their neon covers and sword-wielding heroes, the books seemed ready-made for the big screen. Most of my son’s friends were reading them, too, and the novels were a source of endless discussion. Yet after a half an hour, he’d come back downstairs complaining that the book was boring and that he wasn’t into it.

I pleaded with him to keep trying. I made sure every distracting device had been stowed away. I offered rewards for pages read. I argued that books, unlike movies and television shows, can take longer to get moving, but that their rewards were deeper and longer lasting. But no matter what I said, the books just wouldn’t take.

My son was the tallest kid in his class and still growing. The jeans we’d bought in September were above his ankles by the time the snow fell in December. Maybe, I thought, he had too much energy to sit still long enough to read. Then it occurred to me that maybe he was telling the truth. Maybe the books were boring.

I noticed that almost all of the books he was bringing home were set in fantastical other worlds — worlds replete with warlocks and warriors, princes and minions, demonic overlords and humpbacked underlords. Or else they took place in dystopian hellscapes where technology and bioengineering had become weapons of mass destruction. Such stories had never appealed to me, even as a kid. Maybe, despite their blockbuster popularity, they didn’t appeal to my son, either.

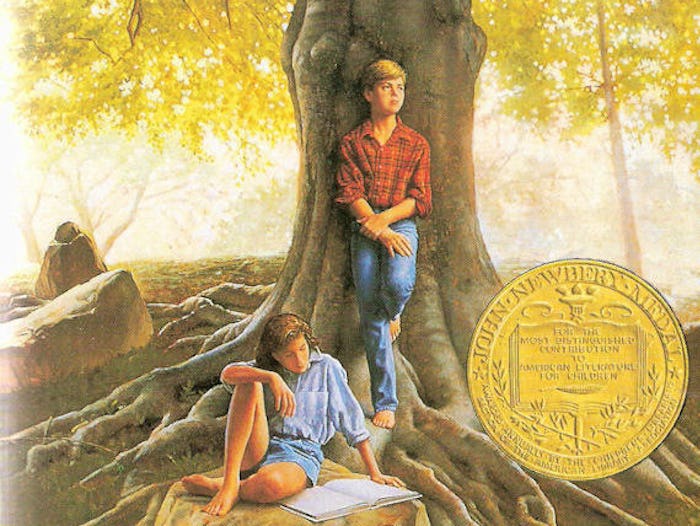

One day in April I brought home a different book for him to try: Bridge to Terabithia, Katherine Paterson’s 1977 novel about a fifth-grade boy, Jesse Aarons Jr., and his unlikely friendship with the new girl in school, Leslie Burke. Set in rural Lark Creek, Maryland, Jess is an outsider: the lone boy among four sisters and a talented artist branded by his schoolmates as “the crazy little kid who draws all the time.” Jess especially longs for his father’s affection, even though affection, like money, remains in short supply.

Leslie, too, is a misfit in Lark Creek. A tomboy who can outrun all the boys, she calls her parents — writers who decamped to the country for a simpler life — Bill and Judy rather than Dad and Mom. After suffering parallel humiliations at school (Jess is teased for his art, Leslie for admitting she doesn’t own a television), the friends set out to explore the woods at the edge of the farmlands, swinging on an old rope across a dry creek bed. Ensconced in the thick pines, Leslie proposes that she and Jess invent a magical kingdom — Terabithia.

Jess and Leslie cobble together a lean-to shed, which they name their “castle stronghold.” To the fort they add only the barest essentials: a coffee can filled with dried-fruit and crackers, some nails and string, five washed-out Pepsi bottles filled with water. The castle stronghold, it turns out, isn’t much of a castle, nor is it very strong. But that’s precisely the point. Terabithia is only magical if no one but Jess and Leslie can find it.

In the 2007 adaptation of Bridge to Terabithia, Jess and Leslie swing across the creek bed into a world of big-budget special effects. A tree turns into a giant troll, elfin warriors emerge from the forest, and an enormous falcon plucks Leslie off her feet. With every new creature they encounter, the children’s faces register stunned surprise. At one point Jess even exclaims, “This can’t be happening!” In the hands of Disney, Terabithia is a world nearly as fantastical as Lord of the Rings.

In the novel, however, Jess and Leslie never forget that their magical kingdom is imagined. Nothing dwells in the forest that the kids don’t create for themselves. Sometimes they do nothing more than linger in the deep silence of the woods. Paterson writes, “They stood there, not moving, not wanting the swish of dry needles beneath their feet to break the spell. Far away from their former world came the cry of geese heading southward. Leslie took a deep breath. ‘This is not an ordinary place,’ she whispered. ‘Even the rulers of Terabithia come into it only a times of greatest sorrow or greatest joy. We must strive to keep it sacred.’”

I worried more about him losing his sense of wonder, that sacred and awe-filled feeling that comes from allowing the imagination to take flight.

As a younger boy, my son plunged freely into his own myriad Terabithias. He’d built forts behind the garage and forests of blankets in the basement and turned his bike upside down to pretend it was an ice-cream machine. But somewhere along the line, he’d become self-conscious about make-believe, as though it were something to be ashamed of. Now on the cusp of junior high, he’d suddenly taken an interest in his hair and clothes. He begged me for a cell phone and an Instagram account. He worried about being left out. I worried more about him losing his sense of wonder, that sacred and awe-filled feeling that comes from allowing the imagination to take flight.

Thankfully, unlike the other fantasy and dystopian novels he’d brought home that year, my son became positively engrossed in Bridge to Terabithia. Every night for a week, he lay on his bed with his ankles crossed and the book propped on his chest. If I interrupted to check on him, he didn’t set the book down; instead he waited for me to leave so he could get back to the story. He wouldn’t quite admit it, but I think he loved the novel because he identified with Jess and Leslie in a way he never could with the characters in the other books. Their struggles — to trust their feelings and overcome their doubts — were his, too. And the hours he spent in Jess and Leslie’s imagined world seemed to offer him a reprieve from the pressures of his own.

Bridge to Terabithia, ironically, isn’t a happy story. At the end of the novel, Leslie dies when the old rope swing breaks, plunging her into the creek that — thanks to weeks of rain — has become a river. The night my son finished the book, he came down the stairs blanched with sadness. He slumped on the couch beside me, his eyes red and wet with tears. It wasn’t right, he said. It wasn’t fair. Leslie was the Queen of Terabithia! I put my arm around his shoulder and pulled him close — not so unlike the way Jess’ dad gathers him into his arms to comfort him in his grief. My son took a deep breath and asked me if Katherine Paterson had written any other books. He might want to give those a try.

The next day was sunny and warm. When I looked out my bedroom window into the backyard, I saw my son lying on the roof of the shed behind the garage. He lay with his arms crossed behind his head and his eyes closed in the sunlight. I could only guess at the worlds he was traveling in.

David McGlynn is the author of One Day You'll Thank Me: Lessons From an Unexpected Fatherhood (June 2018) from Counterpoint Press.