Life

The Book That Changed How I Will Raise My Future Daughter

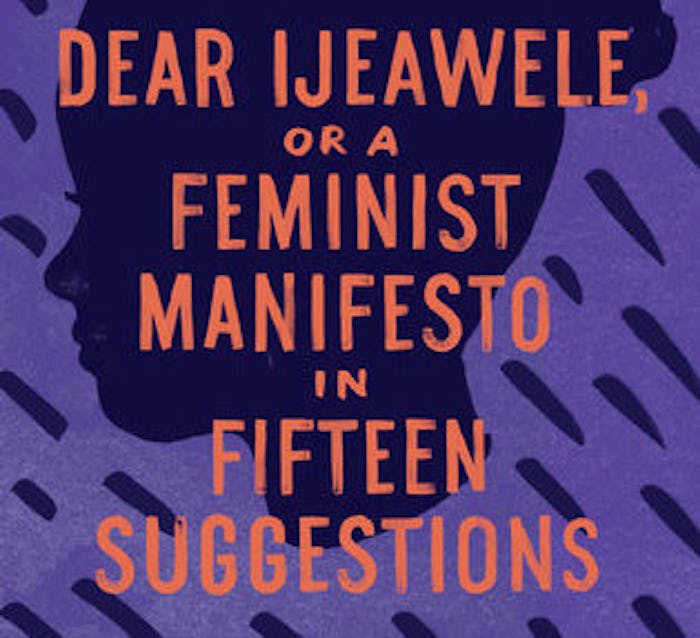

When I first read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, I felt like a mirror had been held up to my life. Written in response to a fellow Igbo friend asking for advice on how to raise her daughter feminst, Adichie provides 15 suggestions while simultaneously detailing the sexism in Igbo culture.

Growing up an Azerbaijani woman, I was no stranger to the sexist traditions and practices Adichie describes throughout the letter. Many of her suggestions are related to ideas I’d already learned to reject, such as marriage being seen as a prize, starting a family being a requirement, familial roles on the basis of sex and the cloak of likability and graciousness girls must keep on at all times.

These are easy enough to teach my future daughter, but what about the factors that aren’t within my control? How will I navigate raising a daughter in a fixed environment, while my inherited shame trails behind me?

To say I’d always known what a “woman’s place” is in my culture would not be an exaggeration. I became aware of what was expected of women when my mother decided to pursue a bachelor’s degree in the U.S., with three young children at home. At 7 years old, I heard daily arguments between my mother and grandmother, sometimes including her male cousins, about choosing work over her kids.

The question of whether she was being a good mother constantly played on her mind while she worked to make a better life for us.

I couldn’t understand their point of view, because surely more money and food on the table wasn’t a negative. She was working harder than anyone I’d ever known, poring over English-Russian dictionaries and laboring over assignments all through the night. But to anyone who believed or had grown used to the idea of women being tied to the home, she was betraying her kids.

My mother eventually finished her bachelor’s and went on to get her master’s degree and license in social work, placing her at the top of her field. This was not without its difficulties, and the question of whether she was being a good mother constantly played on her mind while she worked to make a better life for us.

But if I had been more impressionable and my mother ended up listening to the voices of close friends and family telling her to give up, I wouldn’t be able to brush off the relatives who dismiss my dreams of being a journalist with a laugh and a sigh. She showed me that there’s so much more to life than being a mother.

What she didn’t account for were the people who would try to deter me from my goals, or the familial environment I had no choice but to grow up in. How was I to protect my daughter from discouragement or false ideas about women when family is central to our culture? This is where Adichie provided a fresh perspective: surround your daughter with alternatives, whether that be an uncle who loves to cook or a strong, confident female friend.

My inherited shame was even less of an easy fix. When I turned 13, the female body became linked with shame. Shopping for special occasion dresses with my mother meant making sure they weren’t too short, so people wouldn’t make assumptions about my promiscuity, and long enough to warrant respect.

As if being prepped for press, on the night of a wedding or major event, I was told that I could never be seen with a drink in hand nor dance too shamelessly, especially not with a boy. The message was loud and clear: I was being watched and judged.

If this shame manifested itself in unconscious ways, how could I be sure I wouldn’t pass it on to my daughter?

The confirmation came at a family picnic in 2014, when a well-meaning relative pulled me aside and informed me that my dress was inappropriate. I looked down in confusion; I had on a black dress that was only an inch or two above my knees. Where was the issue? But, of course, it had more to do with how the dress clung to my body than the length. I knew the comment wouldn’t have been any different if we were at a wedding.

One comment was enough to set off millions of hypothetical criticisms in my mind, so much so that I can still feel them picking at the edge of my skirt or harshly pulling up a low-cut shirt. If this shame manifested itself in unconscious ways, how could I be sure I wouldn’t pass it on to my daughter?

Adichie answered in full: “To make sure she [your daughter] doesn’t inherit shame from you, you have to free yourself of your own inherited shame. And I know how terribly difficult this is. In every culture in the world, female sexuality is about shame.”

Before reading this part, it hadn’t even occurred to me that I was carrying borrowed shame. Although unlearning these thought patterns will take years, it’ll save me and my daughter the trouble of valuing “them” over “us.”

But most importantly, Adichie reminded me that being critical of my culture’s sexism does not mean rejecting it entirely and encouraging my daughter to follow suit: “You must be selective — teach her to embrace the parts of Igbo culture that are beautiful and teach her to reject the parts that are not.”

There is still joy in embracing the positive aspects — the beautiful country, how close-knit and loving the Azerbaijani community is and the delicious traditional dishes. I plan to immerse my daughter in this culture, but I also want her to know that she doesn’t have to agree with something to love it dearly; appreciation and criticism are not mutually exclusive.

This article was originally published on