Life

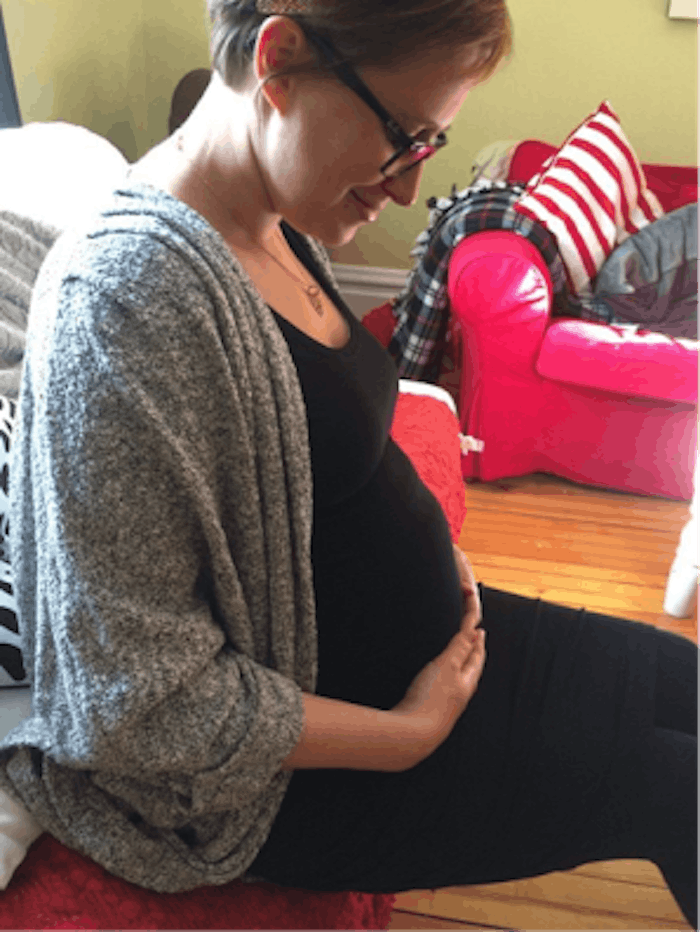

The Devastating News I Got During My Third Trimester

Before becoming pregnant, I had bought into the fantasy that pregnancy was beautiful and exciting and hopeful. I knew that some of my family members and friends had hated their pregnancies, but I wanted to embrace the experience of creating new life in its full totality, morning sickness, swollen ankles, exhaustion, and all.

When I actually experienced morning sickness, however, I realized how wrong I had been, and that the miracle of pregnancy might have been oversold. Regardless, I marched on and tried to remain positive and hopeful, until I came up against a wall I could not overcome.

At the beginning of my third trimester, my daughter was diagnosed with four congenital birth defects affecting her brain. Doctors told us we wouldn't know how they would affect her — whether she would be severely developmentally delayed or developmentally "normal" — until after she was born. Because of a small blip in my daughter's genetic code, I spent the rest of my pregnancy in a state of all-consuming anxiety, thus dashing any hopes that I would enjoy my third trimester. That said, I wouldn't change a thing about my pregnancy, because it gave me the opportunity to know my daughter better than I could have ever possibly hoped for.

Before I entered my third trimester, I felt like I had experienced the true reality of pregnancy: I suffered from 24/7 morning sickness, and I experienced a wide range of food cravings and intolerances. My heartburn was like an all-consuming fire in my chest, neck, and jaw, but my skin and hair had never looked better. And I watched with excitement and some horror as my breasts, then my butt, and finally my belly popped. I felt lucky and excited to be able to experience all of it.

28 weeks into my pregnancy, however, my husband and I were given news that changed everything. My doctor told us that my daughter had a brain disorder, agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC). The corpus callosum consists of a bundle of nerves that sits in the centre of our brains and passes information between the left and right hemispheres. Yet my daughter didn't have a corpus callosum. It simply never had grown.

At a time when I should have been feeling excitement for the arrival of my child, I felt nothing but dread.

The worst part about this diagnosis was that we had no idea how it would actually affect my daughter's development, because the symptoms of ACC range widely. A person with ACC may need a feeding tube and never grow out of diapers. They may never speak. They may have problems with appropriate social behaviour and emotional outbursts. Or they may present as completely neurotypical. The effects of ACC depend on numerous factors, including what caused it and how the brain adapts to the lack of a corpus callosum.

My doctor had no way of knowing how my daughter would be affected by her ACC until she was born. But we did know she would also be born with colpocephaly, a brain disorder that can affect cognitive development, and septo-optic dysplasia, an underdevelopment of the optic nerve that can cause blindness, vision impairment, or affect pituitary gland function.

My husband and I received this news on the same day that we started to decorate my daughter's nursery. I was crushed. At a time when I should have been feeling excitement for the arrival of my child, I felt nothing but dread.

Everyone jokes that the third trimester is when women just want their pregnancies to be over. But I spent my third trimester trying to bargain with the universe to let me be pregnant for the rest of my life. I didn't want to give birth because I felt that if I didn't give birth, I wouldn't have to know what kind of hardships my daughter might have to face in life. I dreaded my baby shower, and then I felt guilty for that dread because my best friends had gone to great lengths to ensure I would enjoy it.

I obsessed over the idea that I had done something to cause my daughter's birth defects. I cried all the time, mostly when I was in the shower or on the drive to and from work. I felt scared and angry and alone, even though my husband was right there beside me. I had thought that everything would be fine. I'd stupidly believed that bad things don't happen to good people, and that sick babies aren't born to healthy mothers. But I had been wrong. I had hoped that my pregnancy would be a beautiful, positive experience, and my hope had betrayed me.

Then my daughter arrived. And she was fine. Fine, in fact, might be an understatement. Her geneticist, neurologist, and pediatrician have all remarked more than once since her birth that if they didn't have definitive proof, in the form of two MRIs, of her birth defects, they would assume she is a "normal" child. She has hit all of her milestones so far, and she is wonderfully, beautifully healthy. She may still encounter issues related to her ACC later in life, and as she gets older, she may have trouble learning abstract concepts. She might have behavioral issues or be socially awkward. But for now, I am, once again, hopeful.

If I hadn't known her diagnosis before she was born, I never would have had to endure those 9 weeks of fear and anger and hopelessness.

I've been asked by my friends and family, even her doctors, if I wished I'd never known about her birth defects. If I hadn't known her diagnosis before she was born, I never would have had to endure those 9 weeks of fear and anger and hopelessness. I could have saved myself the tears. I could have enjoyed every moment of my pregnancy without the whisper in the back of my mind that my daughter would live a life of constant suffering or struggling, and it was all my fault. I could have enjoyed my third trimester. I could have complained about back pain and swollen ankles and the fact that my wedding ring no longer fit (all legitimate complaints, by the way). I could have been excited to meet my daughter.

Despite all that, I know now that I wouldn't have had it any other way. I would take the pain and fear all over again. Because now, I truly understand what the words "miracle of life" mean. They have nothing to do with pregnancy. They have everything to do with hearing my child say "Mama," seeing her run in the park, seeing her laugh and play, all while knowing that she is missing a piece of her brain. I have seen the negative space inside her head, and I know now what I did not know in my last trimester: that it does not define her. I just wish I had not let it define the last weeks of my pregnancy.