Life

Is The HPV Vaccine Safe For Boys? It's Recommended For All Young People

Anytime a conversation occurs around vaccines, there is almost always controversy. Years of debate surrounding safety and efficacy, coupled with the easy dissemination of information on the internet that is often not backed by actual science has led many parents to feel uncertain about what is really best for their children, and whether they should follow their doctors' orders when it comes to vaccinating their kids. This issue is perhaps most heated when it involves infants and young children, but kids and teens still need vaccines, too. Is the HPV vaccine safe for boys? The idea of giving the HPV vaccine to boys is relatively new, but medical experts widely agree that not only is it safe to do so, it should absolutely be done to save lives.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, HPV (human papillomavirus) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States — so much so that nearly all men and women who have had sex (even if it's only been with one person) will likely acquire it at some point in their lives. But to be more accurate, HPV isn't just one virus, but a group of about 150 viruses, which are transmitted through skin-to-skin contact (including vaginal, anal, or oral sex, which is how it is most often transmitted). Part of the reason why it's so easy to get? People with HPV don't always show signs or symptoms, meaning they can pass it on to their sexual partners without even realizing they have it themselves.

This, of course, is where the vaccine debate comes in. Although some strains of HPV can cause genital warts (which is obviously no fun), it was also discovered that other strains of HPV can cause certain types of cancers, like anal cancer, cancer of the mouth and throat (oropharyngeal cancer), penile cancer in men, and cervical, vulvar and vaginal cancer in women. What is particularly concerning is that these types of cancers can take years (or possibly decades) to develop after the individual first contracts HPV, according to the CDC, and what's even worse is that, in many cases, symptoms do not occur until they are very advanced, making them extremely difficult to treat.

For most people, HPV is something the body can fight off on its own with few (if any) ill effects. But since the risk is so high for those who develop HPV-related complications (and since there is no way of knowing who those people will be), the CDC now recommends that all children be vaccinated for HPV at age 11 or 12 as part of their routine vaccination schedule.

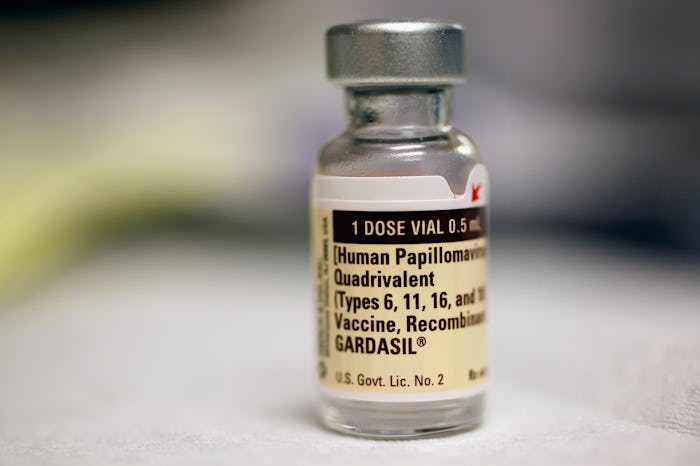

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the three-dose Gardasil vaccine is most effective when given to boys and girls at 11 or 12 years, before they become sexually active. It can also be given to females up to age 26, or males up to age 21 (in some cases also up to age 26), though is it thought to be less effective the older the patient is. The vaccine is thought to prevent "most cases of cervical and anal cancer in females" so long as it's been given before any exposure to HPV, can prevent "most cases of anal cancer" and "head and neck cancer caused by HPV" in males, and can also provide protection from genital warts. The AAP says that the Gardasil vaccine is "very safe," and that, while the majority of people report no side effects from the shot at all, the most common side effects from those who get them are mild, and similar to those of pretty much every other vaccine: pain, redness or swelling in the arm where the needle went in, fever, headache, nausea, or joint pain.

In some cases, the risk of fainting following the shot is elevated, so the AAP recommends patients sit or lie down for 10 or 15 minutes afterward. Overall, however, it recommends that these concerns shouldn't prevent parents from having their children vaccinated:

The CDC has carefully studied the risks of HPV vaccination. HPV vaccination is recommended because the benefits, such as prevention of cancer, far outweigh the risks of possible side effects.

Up until relatively recently, the push for the HPV vaccine had focused on girls, and in some countries with state-funded healthcare programs, like Canada and the UK, the HPV vaccine is given in schools to all girls aged 12 and 13. But with studies showing that HPV-related cancers are on the rise in men, according to NBC News, it's becoming clear that boys are also at risk if they are not vaccinated early as well.

Professor of gynecologic oncology at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Dr. Lois Ramondetta, told NBC News that the increase in HPV-related cancers involving the mouth, tonsils and tongue are proving that HPV vaccinations are important for boys just as much as girls:

In the past, people always felt that the boys needed to be vaccinated to protect the girls but, truthfully, they need to be vaccinated to protect themselves. There is an epidemic of HPV related cancers in men, specifically those of the tonsil and the back of the tongue. What's really important to know about those is that there is no screening test for those.

The benefit of early vaccination, according to Ramondetta, is two-fold: one, vaccinating boys early means they will be protected from HPV before being exposed to it, making it more effective. And two, immune responses tend to be stronger earlier in life, meaning that protection might last longer than someone who gets the vaccine at an older age.

Although any cursory Google search about the HPV vaccine (or any vaccine really, come to think of it) will likely return a host of scary-sounding reasons why giving boys and girls the vaccine is a terrible idea (everything from serious side effects to encouraging promiscuity in young children — both unproven claims), the reality is that the vaccine is recommended across the board by medical experts as safe and effective, and the risk of going unvaccinated is really high. Of course, all parents should do their research and speak to their doctor when making their decisions, but given the protection the vaccine can offer children later in life against deadly cancers, it seems like a pretty easy decision to make.