Life

The Well-Meaning Myths We Tell Our Children

As soon as we become parents, we begin the re-tellings. The rushed Uber ride. The wait, maternity ward mixups, the stitches, the "on the day you were born" clichés SNL sent up this Mother's Day. The story of my birth suffers a blank of a few hours during which my mother underwent an emergency c-section; an ellipsis I've always suspected upsets her. For author Nicole Chung, the lapse in narrative was much longer: for 10 weeks as an infant, she was looked after by hospital staff at a Seattle NICU, before being adopted by a couple from Oregon. As a transracial adoptee, she was given a tidy origin story to retell herself over the years to come: "adoption was the best thing for you."

In the eyes of her adoring adoptive parents, it was predestined that they would come to consider as their own the tiny infant born to Korean immigrants who couldn't afford the cost of her likely medically complicated future. She was "lucky" to have been adopted.

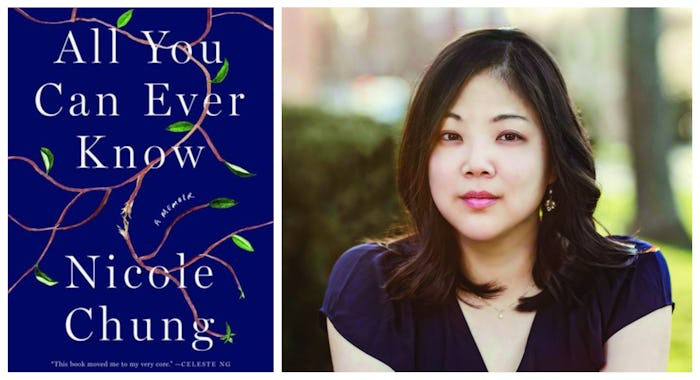

It's a viewpoint that doesn't allow room for the loss of the child who has been adopted, and the single thread that Chung tugs until it unravels something much bigger, much more complex and conflicted in her memoir All You Can Ever Know (Catapult). The book asks parents to examine the myths they pour into their children's heads with good intentions, not questioning the salience of their personal truth for people whose story has just begun. It's a must-read for anyone who has held a newborn in their hands, that surprisingly hefty bag-of-jelly-beans weight, and understood the power they have in shaping the early years, pre-memory.

The midwife asked me all these questions about my birth and family history and I did not know what to tell her.

When she falls pregnant with her first child, Chung begins to search out details about her birth family. Initially, she is looking for simple medical information — why was she born prematurely? Are there risks she needs to know about? — an inheritance many of us who look like our parents take for granted.

"I was sitting at my first prenatal appointment, like, we're going to have the ultrasound, it's going to be great! and the midwife asked me all these questions about my birth and family history and I did not know what to tell her," Chung tells Romper by phone.

The initial request for sealed "non-identifying information" about her birth parents on record in Washington State leads to bigger what-ifs.

"It's sort of natural for adoptees to wonder, What would it be like if I were in a family different than my own?" Chung says. "If you're adopted, you wonder what would have happened if your birth parents kept you or maybe if you'd been adopted by different people."

Understandably, adoptive parents are less likely to consider such hypotheticals, less likely to view adoption as a trauma resolved by reunion than the other way around (as Jeanette Winterson, an adoptee, writes in The Gap Of Time, her retelling of A Winter's Tale, "It takes so little time to change a lifetime and it takes a lifetime to understand the change.").

Challenging this viewpoint is subversive in itself — it was the germ of an essay exploring transracial adoption published on The Toast in 2014, when Chung was managing editor — but the book goes much further than that, decentralizing the story entirely when it introduces the character of Cindy, Chung's birth sister, in what amounts to a co-starring role — the shared heart of the piece.

If Chung has often been pressed to offer a binary opinion (good/bad?) on transcultural and transnational adoption, it's easy as the reader to want to evaluate the life of Chung's birth sister, who is older by six years and remembers their mother being pregnant with Chung, as a better/worse? kind of prospect. But piecing together Cindy's life, nothing is quite as simple.

"When I found out about Cindy and her life, it was moving and very beautiful and an opportunity to understand a little bit of what my life could have been like," Chung says. "She and I both saw it in the other person what it would have been like if our parents made different choices."

The idea of a sister had of course occurred to Chung: "The first time I asked someone to be my sister, I was ten years old," she writes in the book. And as Cindy's story is told, in concert with the birth of Chung's eldest daughter, a different kind of loss crystallizes for each sister.

The emotional overhang of the adoption is well-known to Chung, but when she sees the first ultrasound of her future daughter, she realizes the physicality of it:

"I was going to be a mother. Someone would depend on me. Our relationship would last for the rest of my life; though it had yet to begin, I could not imagine it ending. Yet that was exactly what happened to the bond between me and my first mother: it had been broken. We had both survived it, learned to live apart, and while I knew this — had known it for some time as long as I could remember — it had never struck me as unnatural until I heard my own child's heartbeat."

All You Can Ever Know is an incredible, humanist look at adoption, and an exploration of the scars Chung has from the subtler, unlabeled racism she experienced growing up in a homogenous plot of America, far from other Asian Americans (a crucial piece of the adoption conversation Chung has helped others to explore as an editor at Hyphen, an Asian-American literary magazine). But adoption or not, the book should be required reading for anyone contemplating parenthood.

I remember my eldest child telling me once, 'It makes me sad that you grew up in the hospital for two months.'

Now a mother to two girls, Chung says she conscientiously gives her kids space to sit with whatever they feel.

"I remember my eldest child telling me once, 'It makes me sad that you grew up in the hospital for two months.'" Recalls Chung. "It would be tempting to tell her, 'Oh, it's OK, because everything worked out,' but I wanted to encourage her to feel however she felt about the facts of my life."

There is an idea that in preparing for parenthood, we have to get our stories straight about the past. As Meaghan O'Connell wrote in And Now We Have Everything: On Motherhood Before I Was Ready, "We all talked like we were going to eventually reach some grand conclusion, some correct stance, but in fact it was different for everybody, impossible to pin down. Was childbirth traumatic or transcendent?"

The inverse seemingly allows greater growth, a new, more fully realized experience, whatever it is. Chung's story is proof that you can't second-guess where a child's most searing pain will come from in absorbing the various pieces of their family's history. Cindy's story offers uplift and hurt — how should we understand the lives of the children who weren't given up for adoption? It's a question I'm not even sure how to type.

I grew up hearing this one very simple story about my adoption, and I still feel a great deal of sentimental attachment to that story.

"I was really interested when I wrote this book in all the people out there who have those questions, who are curious about some of those missing people or those missing relationships, or in my case that entire missing culture, and what makes you decide to pull on those threads, instead of just accepting what everybody tells you, which is that it's done, or it's in the past, or it's not relevant to who you are," says Chung.

"I grew up hearing this one very simple story about my adoption, and I still feel a great deal of sentimental attachment to that story."

But as she proves here, there's more heart and hope in taking a narrative leap. Watching her young daughter play, her birth sister beside her on the couch, she writes, "I felt so happy that, for the rest of my life, these early days of motherhood would be inextricably linked with my first memories of Cindy."