What Fidel Castro's Death Means To Me As A Cuban-American Mother

Yesterday, I woke up to the heartbreaking news that Florence Henderson, my childhood example of the "perfect American mother," had passed away. Less than 24 hours later, I woke up to news of yet another passing, this time of a man whose life had been the catalyst for my own mom's journey to becoming an American mother: Cuban dictator Fidel Castro.

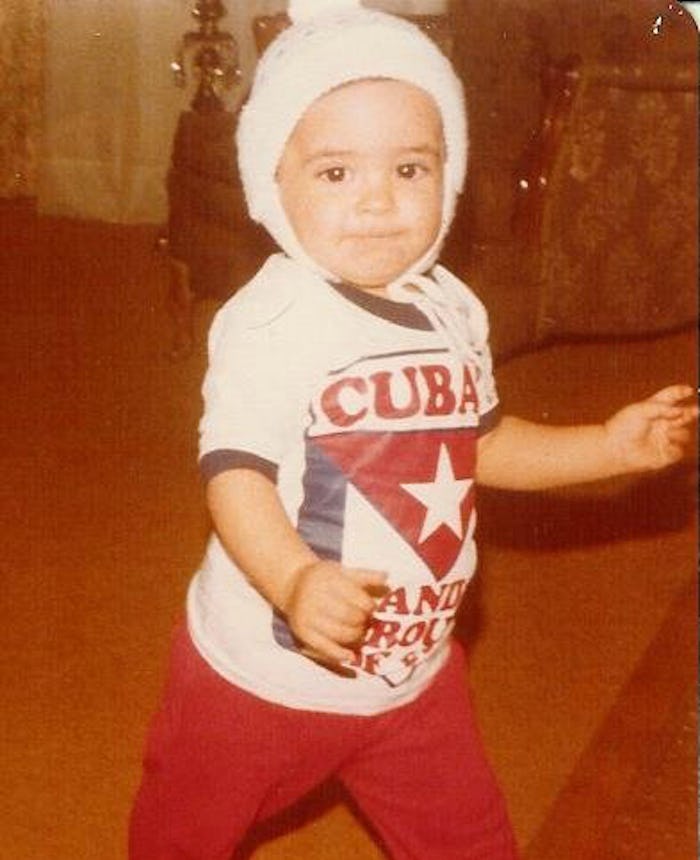

I am a Cuban-American, and for years, early Cuban exiles like my parents held out hope to one day return to their birthplace. Even though the majority of us were born in the United States, the children of Cuban exiles were raised to believe that we were Cubans first: we spoke Spanish at home, cooked Cuban food, listened to Cuban music, watched Spanish-language television, and celebrated traditional Cuban holidays.

But, as time passed, we knew that we had to assimilate and embrace being Americans, something my parents did proudly in 1994 when they became citizens. Because of their sacrifice, I can't picture my life anywhere but in this great country. My history and my blood is Cuba, but my heart, my life, and my future is America. Unfortunately, Castro's communist regime made it such that my parents' hope to bring us all home again was lost.

Because the Cuban government took away all of my parents' property and hope for financial independence, they had to leave behind all they'd ever known and start their lives over, raising children in a completely new environment. I can't begin to understand how they feel today, still strangers to their homeland nearly 50 years after moving to the United States. They are so completely different than the people who stayed in Cuba or were born into the Castro regime, and yet nothing like the Americans whose ancestors came here hundreds of years ago.

Now that Fidel Castro is gone, what does that mean for my parents' dream of going back "home?"

Fidel Castro did this. In his so-called attempt to socialize and unify a nation, he tore us all apart. But his dictatorship ultimately made us stronger as individuals. Cuban exiles and their descendants have become people of many languages and many cultures. We are doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers, musicians, actors, writers, Olympic athletes, senators, and presidential hopefuls.

But, now that he's gone, what does that mean for my parents' dream of going back "home?" That dream, I am afraid, will never come to fruition, not as long as any Castro is in power. As Herbert Matthews who interviewed Castro in the 1950s wrote in the New York Times, “We are going to live with Fidel Castro and all he stands for while he is alive, and with his ghost when he is dead.”

My parents will continue to go back to visit relatives and bring them necessary medicine and clothing, but they will not be setting up a permanent home in Cuba again. That ship sailed long ago. They, after all, are Americans.

When I was younger, I dreamed of the day when Castro would die. That sounds gruesome, but I knew enough to anticipate that Cuba would never be free under his leadership, and he would never willingly give up power. My dream was to buy a home on the island and bring my family back to our roots. But after visiting the island in person, and ultimately becoming a mother, I see things very differently.

I knew at that moment that I wouldn't be raising my children in Cuba, no matter when Castro died.

I've been to Cuba only once. In the late '90s I accompanied my mother on a trip to meet my uncle and cousins. For the children of exiles, going to Cuba for the first time is like going to the moon: it's a place we know exists, but on which we never actually believe we'll set foot. I hid rocks in my pocket and breathed in the air, smelling cigarettes and diesel fuel. I chewed on sugar cane at a relative's farm, sat on the wall of El Malecón in Havana, looked up at the crumbling buildings, and had to convince myself that this was all real.

One of my strongest memories was spending time at the local preschool, the "círculo infantil," and seeing the children in hand-me-down clothing, napping on towels over a concrete floor while their teachers chatted and smoked cigarettes over their little sleeping bodies. I knew at that moment that I wouldn't be raising my children in Cuba, no matter when Castro died.

Almost 20 years later, Castro is finally gone and my children are Americans of Cuban descent. My husband is also Cuban-American, so we have done our best to continue some of the traditions our parents and grandparents brought with them. But the truth is that our kids don't identify as Cuban the same way we did growing up. We speak English at home, and only now, as teenagers, are they showing any interest in their heritage.

Hopefully Castro's death is the beginning of the end of communism in Cuba, and if so, maybe it will open the door for my family to become more connected to our roots. It is important to us that our children understand the history of the Cuban people and how that relates to them. We talk to them about the sacrifices their grandparents and great-grandparents made to get to freedom, and teach them to be grateful and appreciative of all that they have.

When we told them that Fidel Castro died today, they asked, "Is that a good thing?" "Yes," we answered confidently. But the truth is, only time will tell.