News

What Happened To Penny Beernsten, The Woman Who Identified Steven Avery As Her Attacker On 'Making A Murderer'?

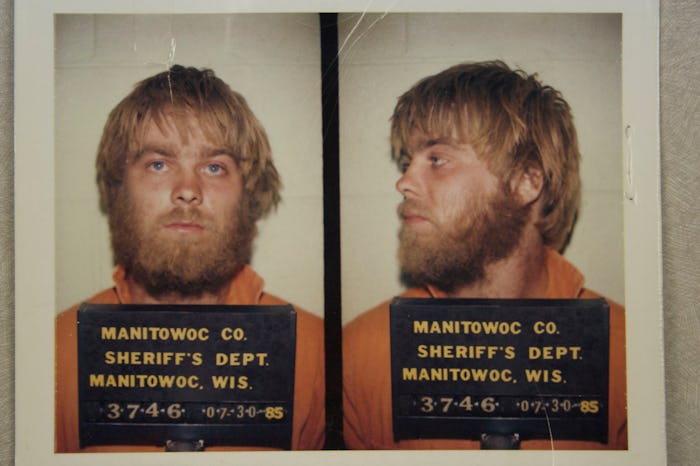

Watching Netflix's compelling documentary series, Making A Murderer, is addictive. The labyrinthine-esque twists and turns of the cases, trials, and small town politics at play in the story of Steven Avery — who served 12 years in prison for a crime he did not commit, only to be exonerated then charged with another high-profile crime — are as captivating as they are maddening. Amid so much intrigue, however, it is important to remember that these aren't characters involved in Avery's story; they're real people. And that includes the woman who wrongly accused Avery of attacking her in 1985. But after her role in the larger story of Steven Avery had ended, it was easy to viewers to wonder what happened to Penny Beernsten.

In Making A Murderer, Beernsten is described as "a leader of the community ... a shining example of what Manitowoc would like its citizens to be." She was educated, affluent, a wife and mother, and she and her husband had several commercial ventures in town, according to the series. The Beernstens stood in stark juxtaposition to the Avery family, whom the docuseries paints as being disliked within the Manitowoc County, Wisconsin community.

In July 1985, while enjoying a day at a state beach on Lake Michigan with her husband and daughter, Beernsten decided to go for a jog. It was then, the series says, that a man in a leather jacket dragged her behind the sand dunes and attempted to rape her. She was severely beaten and left for dead, but was found and taken to the hospital. Her subsequent photo identification, line-up identification, and courtroom testimony naming Steven Avery as her assailant were pivotal in sentencing Avery to 32 years in prison.

In the years between Avery's imprisonment and his exculpation, Beernsten felt a great deal of pain and anger as a result of her assault, according to a speech she gave in 2004. This motivated her to seek therapy and, eventually, speak at prisons to show inmates the impact violent crime has on its victims. As she said in her speech:

I initially went to prisons feeling like I had something to offer, that maybe if the inmates could understand the impact of a crime, they might begin to have empathy for their victims. Little did I realize how much I was going to take from that process, how very mutual it was, and how much of my healing would take place in the middle of a maximum security prison. I also helped start a sexual assault resource center in our community because there wasn't one at the time of my assault.

After DNA evidence came back in 2003 proving that Avery had been wrongfully imprisoned, she was devastated, especially upon learning that her actual assailant, Gregory Allen, had not only been on police radar in 1985 but had gone on to assault other women.

Beernsten had made an error in identifying Avery, but she is not to blame. (Avery himself does not blame Beernsten for what happened, saying upon his release that "I don't blame the victim. It's terrible what happened to her," a sentiment Beernsten described as "grace-filled.") Despite strong scientific evidence concluding that eyewitness accounts are unreliable, it is routinely relied upon in legal proceedings.

In her speech, Beernsten spoke about the importance of reforming eyewitness identification, and described a touching letter she wrote to Avery.

When I testified in court, I honestly believed you were my assailant. I was wrong. I cannot ask you for, nor do I deserve, your forgiveness. I can only say to you, in deepest humility, how profoundly sorry I am. May you be richly blessed, and may each day be a celebration of a new and better life.

She also collaborated with The Forgiveness Project, an initiative that seeks to empower victims and perpetrators by encouraging alternatives to resentment, retaliation, and revenge. She describes a meeting she had with Avery and his parents. At its conclusion, she asked if she could hug him. Without responding, Avery hugged her and said "Don't worry, Penny; it's over."

Things became more complicated for Beersten in 2005, when Avery was accused and later convicted of the rape and murder of Teresa Halbach, a charge Avery has always maintained is false. He is currently serving a life sentence. Beersten was featured in an episode of Radiolab in 2013 entitled Are You Sure? during which she describes how it felt to hear about Avery's fate.

I can't even trust senses. I can't trust my eyes to tell me what I, you know, what I thought I'd recorded accurately about the world. And then when he gets convicted of killing Teresa it's like "What kind of character judge am I?" Now I can't even judge character.

She goes on to wonder if Avery, whom she believes committed the Halbach murder, would have gone on to murder had he not gone to prison. In other words, she questions if she is to blame not only for Avery's wrongful imprisonment but for Halbach's death. "Prison is enormously damaging to guilty people," she says. "What happens to someone who's innocent?"

Beersten is clearly a thoughtful woman who seeks to make positive change in the world. After a horrific assault, she channeled her anger into a positive outlet by working with prisoners. After it was revealed the wrong man had lost 18 years of his life for the crime, she publicly worked through multiple avenues to try to set that right, not just attempting to make personal amends, but to advocate for systemic changes to help others avoid such a fate. Beersten has faced tragic challenges in her life, yet time and time again seeks to not only remain a good person, but to become an even better person. In testimony given to The Forgiveness Project, she said,

The most difficult thing in all this is being able to forgive myself.

We sincerely hope that Ms. Beernsten can continue to heal and forgive as time goes on.

Image: Netflix (3)