What Is The Avery Bill? Netflix's 'Making A Murderer' Explains

Not your typical Netflix binge-watch, Making a Murder is a compelling and chilling look at the criminal justice system and rural politics. The subject of the documentary, Steven Avery, was exonerated after 18 years in prison for a brutal rape that DNA evidence later showed he didn't commit. One result of his experience is the Avery Bill. So what is the Avery Bill in Making a Murderer? The Avery Bill aimed to reform police and prosecutorial conduct, and targeted methods allegedly used by Wisconsin cops to coerce confessions from underage and unrepresented citizens.

According to The New York Times, the bill was composed following Avery's release to avoid the mistakes and alleged corruption that led to his wrongful conviction. Additionally, as cited in the Wisconsin Law Journal, key provisions of the Avery Bill included:

electronic recording of both juvenile and adult felony suspect interrogations; required written police policies governing the eyewitness identification procedures; priority DNA testing in post-conviction cases; new provisions for retention of evidence that contains DNA.

At the time the bill was gaining momentum, Avery's civil rights attorney Steven Glynn said in Making a Murder,

Steven was becoming like a celebrity in the criminal justice system. I'm talking, politicians from the governor down to the state legislator who would be a prime mover in the Avery task force.

That state legislator was Representative Mark Gundrum of the Wisconsin State Assembly. Gundrum said in Making a Murderer that he saw Avery's case as a catalyst for change in the criminal judiciary system.

Avery was accused of sexually assaulting a local business owner, Penny Beernstein, on a beach in 1985. The prosecution's case relied heavily on eyewitness testimony supported by a composite sketch of Avery, who looked similar to Gregory Allen, the man later confirmed as Beernsten's attacker. According to one of Avery's defense attorneys, his defense provided 16 different witnesses to confirm his alibi at the time of the attack. The jury convicted him in only four hours.

Avery was sentenced to 32 years in prison for sexual assault, attempted murder, and false imprisonment, according to the Innocence Project. It wasn't until DNA evidence—from a pubic hair taken from the sex kit in 1985 that matched known sex offender Gregory Allen—that Avery was exonerated.

In his remarks to the Wisconsin State Assembly, Avery said he didn't want what happened to him to happen to anyone else. He also emphasized that he didn't want what happened to the victim Penny Beerntsen to happen to anyone else. Unfortunately, it had. Gregory Allen brutally raped another woman while Avery was in jail. Allen is now serving a 60-year prison sentence for a 1995 sexual assault.

In 2005, with support from Wisconsin Innocence Project, an organization that championed Avery, the Avery Bill, which modifies eyewitness protocol, along with several other procedural reforms passed in both houses of the state legislature. In the meantime, Avery had begun pursuing a civil suit against the Manitowoc County Sheriff's department asking $36 million in damages. The suit accused the Manitowoc County Sheriff's department of purposely hiding evidence, specifically, knowledge of sex offender Gregory Allen, who admitted to being in the Manitowoc area when Penny Beerntsen was attacked, as well as suppressing this evidence at all of Avery's appeals.

The Wisconsin legislature passed the Avery Bill on Oct. 31, 2005. However, it has since been renamed the "Criminal Justice Reforms Bill" after Avery was subsequently convicted of the murder of a young photographer, Theresa Halbach, whose body was found the day the bill passed.

Avery dropped his lawsuit against the Manitowoc County Sheriff's department and agreed to a settlement that dismissed accusations against the sheriff's department and district attorney. He used the lump sum of cash to mount his defense in the Halbach case. In 2007, he was sentenced to life in prison.

Making a Murderer—a project shot on a scant budget made up of grants, and which took over 10 years, according to The Atlantic—investigates whether Avery was framed, targeted by the Manitowoc Sheriff's Department and subsequently, perhaps even intentionally, failed by the judicial system. If he was — and that's a bigger "if" since the prosecutor in the Halbach case claimed that the creators of Making a Murderer excluded evidence incriminating Avery from the documentary — the legislation formerly known as the Avery Bill didn't help the man who inspired it.

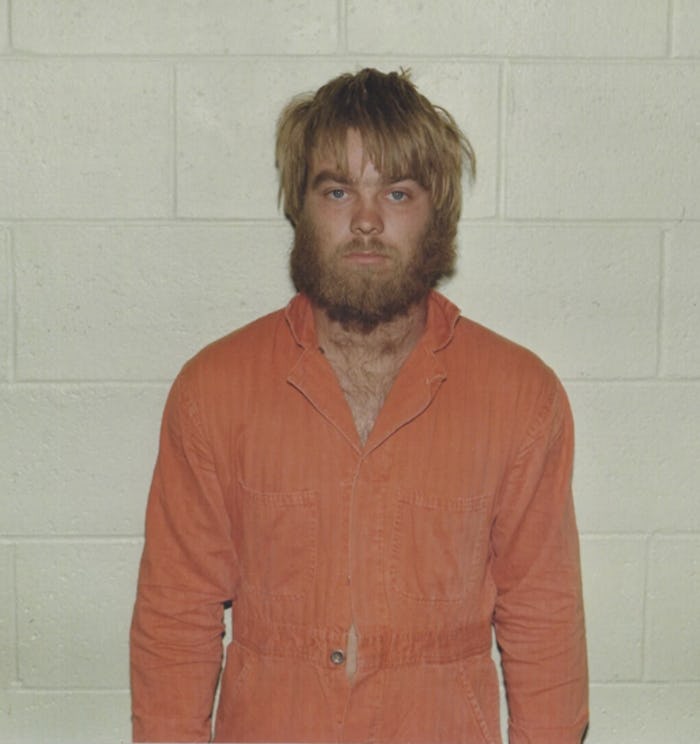

Images: Netflix