Life

The Children's Book That Takes On Death

Reading a book 200 times is a surefire way to find out whether you love it or want to throw its rhyming llama couplets into the diaper pail. Children's books especially do a tricky dance for an audience of squinty-eyed parents and wide-eyed tots: the best ones, like a syringe of infant-suspension Tylenol, have a little something for the parent at the end. These are the ones we are celebrating in This Book Belongs To — the books that send us back to the days of our own footed pajamas, and make us feel only half-exhausted when our tiny overlords ask to read them one more time.

On the scruffy trail to the top of a peak in the Adirondacks a few years ago, my husband and I passed a family of French-Canadians. The mom, dad, and their respective junior models were each tan, lean, with tibias long like batons, and faces honest and open. "Morning," we chuffed as we passed them, hurrying along in our stout bodies. As we sat on the summit a little while later eating our chocolate Clif bars and chugging a beer as self-reward, the family reached the top, striding onto the rocky outcrop where they took in a great, collective inhale, filling eight robust lung sacs, then sat down to share a Zip-lock bag of carrot sticks.

Carrot sticks!

There was, I saw, a gulf between their lichen-covered rock and ours. I glommed slowly onto the idea that these exotic Montreal creatures had not summited solely to gain access to candy, but had found something edifying in the actual slog of it. I pictured them going home afterward to enjoy a couple of hours more leisure time on their wooden glockenspiels or playing with pastel Maileg rabbits, while I sat in the car reading a junky profile of the latest model Leonardo DiCaprio was dating on The Cut. The difference was in their Europeanness, I thought, even as French-Canadians. Their inherent connection to Heidi, to The Alps, their sensibility for Goddard and capacity for netting momentary bliss in the modern world. I didn't feel it. I was squat, impatient, constantly feasting on junk, often taking my husband for granted. But then I also wasn't a parent yet. I scarfed down another energy bar, and my husband and I hurried back down into the scrub, rushing rushing rushing. Bag another mountain tomorrow.

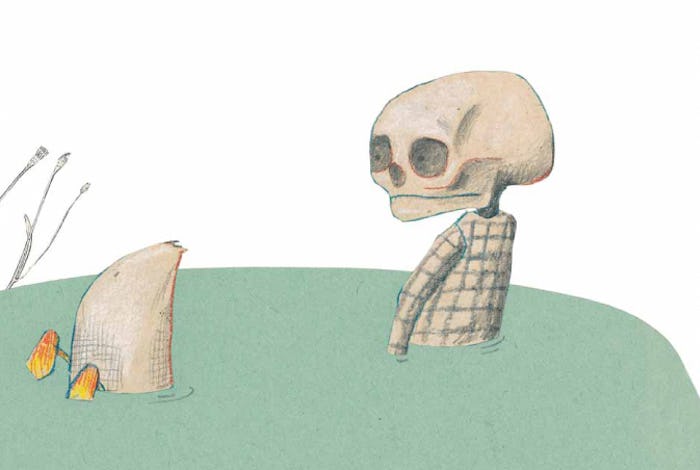

There is a children's book celebrated among literary types that stands quite apart from anything else. I first heard about Duck, Death, And The Tulip at a book event where author Mac Barnett called it out as the pinnacle of what a children's book can be. Unlike other kids' books, it has an endorsement from Meg Rosoff on the cover. There is a certain weight to its heavy stock pages. It seems ~important~. Written by German author Wolf Elbruch, the story begins the day Duck notices Death is following her. At first she is scared, but Death — who, by the way, is a skeleton in a dress — explains that he has always been there. They play. Death begrudgingly swims in the pond Duck loves, painted a brilliant, opaque turquoise that swallows their bodies, and Duck comes to feel a kind of comfort in Death's company. When he is chilly, she offers to warm him.

'That’s what it will be like when I’m dead,' Duck thought. 'The pond alone, without me.'

One day, Duck looks at the pond and has a little epiphany: "'That’s what it will be like when I’m dead,' Duck thought. 'The pond alone, without me.'”

Death reads her mind and replies, “When you’re dead, the pond will be gone, too — at least for you.”

Duck finds a kind of peace in it. She wakes up on one page happy to find she has ~not~ died overnight. There are short, poignant attempts by Duck at establishing a philosophy, but they go no further than the flat landscape Elbruch gives the reader. It's hard to tell how much time is passing. Children's books often feel like a kind of afterlife in their simplicity.

Several pages later, Duck tells Death she feels cold. Death turns to find Duck is lying very still. He carries her to the river, lays a tulip on her body, and lets her float away. Then, "for a long time he watched her. When she was lost to sight, he was almost a little moved. 'But that’s life,' thought Death."

My voice catches a little as I read the last few pages out loud to my daughter the first time. Then I think, What kind of a parent reads a book about death to their toddler?? Where does this slot into a bookshelf full of talking cats, singing potties, Elmo spinoffs, seasonal board books for Easter and Valentine's Day, Goodnight Mermaids?

Far away, I picture a family of hardy Germans in their long shorts and salmon-colored t-shirts climbing onto their blond-wood bunks after dinner for story time, and then discussing death, oblivion, and the Holocaust while Schubert plays in the background. I picture intellectual 8-year-olds reading Kafka and dads who sound like Werner Herzog kissing their sons on the lips as they bid them goodnight.

What do they know about life they I don't?

The birth of my daughter three years ago was the first time I really saw Death. I would wake up every morning and leap out of bed to look at my baby in her bassinet, two steps from my side of the bed. I couldn't wait to spend time with her. A woman on the street asked me how old she was. "Nineteen days old!" I told her. She narrowed her eyes to do the calculation. Scout seemed equally blown away by our days, by swaying trees, by the random bird mobile my husband found on the curb, which now tinkled over her head in the crib.

When I visited home with my new baby, my mum insisted we take a trip to see my grandmother, Narnie, then 97 years old. It was a nine-hour trip in the car out to the pat red land where the town of Leeton sits. My daughter Scout, at 6 months old, sat in my grandmother's lap, smiling and grabbing her necklace. Narnie tried to bounce this bowling ball of a baby on her fragile lap. Neither of them could walk, but they found a way to play. Months later, my grandmother told my mother that she was ready to go, but didn't know how.

We returned home recently and didn't have time to get out to see Narnie, now 100. I talked to her on the phone as she lay in her bed, told her about Scout, now 3, and Japhy, now 18 months old. I narrated a scene of them toddling around the garden with their ginger hair, hopping and tottering between stepping stones as I held the phone to my ear with one hand and steadied my son with the other. At 100, my grandmother had been waiting for Death for a long time; she found her way into that opaque river a few days later.

As we sit on the couch at bedtime, Scout accepts Duck's passing much more easily than I do. My daughter doesn't see the hard edges that I do; she accepts that "our dog" is ours, but also lives with Tom and Mimi, the retired couple we gave him away to. She "misses" her school friends 10 minutes after school pickup, but understands Narnie as a timeless entity — a person she met once, who is in that photo with her, and whose departure doesn't change the fundamentals of that photo, that name. They only overlapped for three years, but Narnie will be pulled into the future with Scout; the pond might cease to exist when the Duck is gone, but only because there is no one around to remember it. A colleague recalls a time when her daughter referred to anything that had occurred in the past as happening "yesterday." When you've only been alive for 900 days, yesterday does seem rather tall. Children don't see the lines.

When you have a baby in particular, it all feels like it collides, birth and death.

Another great German writer, Heinrich Boll, wrote in The Clown, a novel narrated by a despairing clown in post-war Bonn (same), about the comedy routines his character performed for his audience:

"One of my turns is called: Arrival and Departure, a long (almost too long) pantomime during which the audience confuses arrival and departure all the way through."

When you have a baby, especially, it all feels like it collides, birth and death, creating a crush of time when everything is infinitely more precious. Necessarily, when you have a child, you become consumed with death. People are arriving, people are departing, Death is right beside you.

Elbruch doesn't offer hard answers in Duck, Death, And The Tulip. When Duck tries to figure out if there is a heaven or a hell, Death basically says he doesn't know. In the meantime, they pass time by climbing trees and taking naps together.

As a parent, I'm primed to fear death, to worry about the oblivion coming for my ducklings, but Elbruch, with his characters floating on a flat background outside time, teaches you to at least try to see the gift in mortality. "Actually he was nice (if you forgot for a moment who he was)," thinks Duck of her friend Death. "Really quite nice."

When we hike now as a family of four, we'll often do a short loop in a flat, unimpressive reserve, then sit out with our snacks by a big, gleaming pond. The bigger summits we once bagged are, for now, a little more difficult to reach. We never know how far up the trail we will get before Scout's legs tire, or Japhy wants out of his back carrier.

But that's life.