Life

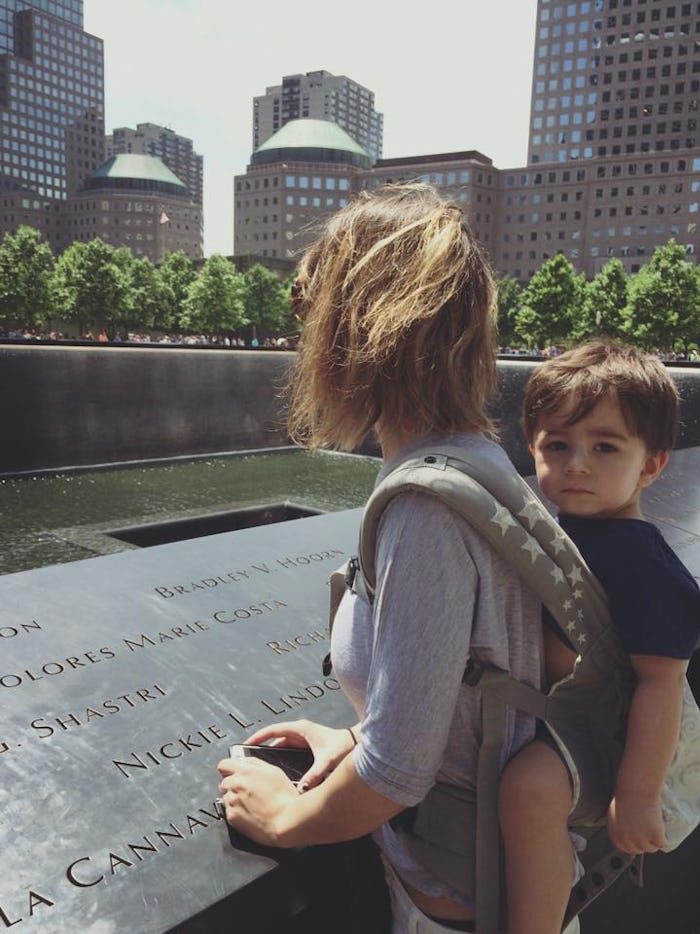

Why I Took My Toddler Son To The Ground Zero Memorial

I walked out of the subway, climbing the stairs with my toddler son on my back. My mother was to my right, wide-eyed and nervous; it was her first visit to New York City. I'd moved to the city two weeks prior, but this would mark my second visit to Ground Zero. There were people everywhere; the hustle and bustle of the city invading every corner of this reverent, solemn place. We passed a sea of tourists, food carts, and boisterous venders selling tickets for Statue of Liberty tours. I knew when I took my son to Ground Zero the mood would be vastly different than my first visit, but the heaviness of a place that once stood for economic freedom and endurance — and that now stands for insurmountable loss, unimaginable courage, and the seemingly never-ending fight against terrorism — remained.

I was 15 years old when I first visited Ground Zero, and it was just two months after the September 11, 2001 attacks. I was with my high school choral group, and we'd traveled from Anchorage, Alaska, to New York City to compete nationally. Our trip was almost canceled, but in the palpable spirit of perseverance that engulfed the country after the Towers fell, we were determined to make the trip regardless of prevailing fear and uncertainty. Parents were nervous, some students declined to go, and we had more chaperones than previously planned, but we went, we competed, and we altered our schedule to see what remained of the World Trade Centers; paying our respects to the horrific loss of life we all viewed from our homes, thousands of miles away. Watching the attacks on television gave us all a feeling of extreme powerlessness, and perhaps paying our respects in person was our way of taking some of that power back.

We'd never know what it was like to be a New Yorker or to lose a loved one that day. We didn't have family members who climbed stairs as the Towers fell, didn't have loved ones who ran into the buildings as chaos reined around them, would never know or understand the agony of waiting hours, days, sometimes weeks, to hear that friends and family had been found. But we knew we could show up to the chained linked fences heavily guarded by military personnel, leave flowers, read the makeshift memorials, and tell the people of New York City that even though we were thousands of miles away on 9/11, we were with them.

I walked off the bus my choir-mates and I rode to the site, the driver a man who was there the day the Towers fell. He told us that he'd selflessly moved people away from Ground Zero, shuttling strangers from danger and out of harm's way. The closer we got, the quieter he became. As we all got off the bus, he told us he'd wait for us there. He told us he couldn't look at the pictures of the still-missing people and the memorials etched on cardboard. He couldn't go to Ground Zero. Not yet. Maybe not ever. As an outsider that day, I still felt the hustle and bustle of the city around me, but it ceased to exist the moment we stepped on the block where the towers used to be. I held my best friend's hand. I cried. No one said a word.

I grabbed her hand, leaned back, and whispered to my son, "This is why your uncle is overseas right now. He's being brave and fighting for all of these people." My mother heard me, smiled, and wiped away a tear.

Fifteen years later, I am a "new" New Yorker now. I live here with my partner and our son. Emerging from the subway on the way to the Freedom Tower, there is no silence. People smile, take selfies, and talk openly about what they remember from that day: where they were, what they were wearing, how they felt. My son happily gibbers on in his toddler talk, holding my mother's hand as we walk towards the marble memorial. I already see her fighting back tears. For her, September 11 marked the day her life would change forever, too.

In the wake of 9/11, my brother decided to become a soldier. Before that fateful day my brother had planned on becoming a mechanic, hellbent on taking things apart and putting them back together. But a few years after the Towers fell, my mom signed a document allowing him to join the Marine Corps at just 17 years old. Since then, he has deployed countless times. The sleepless nights, the painstaking moments she spent crawling news stories for information, the terror, the fear, the endless cycle of what-ifs — they were etched everywhere on her face, each horrifying memory crawling back as we made our way closer and closer to the memorial. I grabbed her hand, leaned back, and whispered to my son, "This is why your uncle is overseas right now. He's being brave and fighting for all of these people." My mother heard me, smiled, and wiped away a tear.

He'll eventually read about 9/11 in textbooks and he'll know that 9/11 is the reason why his father continued to serve in the Navy and why his uncle serves in the Marine Corps. But I want him to know what happened here. He's still too young to understand exactly what happened here, but I want him to understand why people give what they do.

As we walked toward the now-beautiful holes in the ground, symbolizing the two towers and where they once stood, I felt both within and without. I marveled at the beauty of the memorial: the fountain running down the sides of the glistening Twin Towers' footprints to meet and form the reflecting pool, the more than 3,000 names etched in bronze, the well-kept lawns and beautiful trees lining pathways from the two memorials leading to the museum. It felt surreal, as if the place was too beautiful for something so horrific to have once happened there. I traced my fingertips over a name, remembering all of the names scrawled on tattered cardboard and poster board and flyers 15 years earlier, the pictures of loved ones still missing or already gone. I stood with my hands on a bronze panel, my son still on my back, and realized that there isn't a memorial in the world — not even one as beautiful as this one — that could capture the horror or the bravery of that day. I remembered the bus driver I met 15 years prior, the sadness and determination in his eyes.

My son will hopefully never see a look like that. He'll hopefully never witness a city in silence. Yes, he'll eventually read about 9/11 in textbooks and he'll know that 9/11 is the reason why his father continued to serve in the Navy and why his uncle serves in the Marine Corps. But I want him to know what happened here. He's still too young to understand, but I want him to realize why people give what they do. I want him to know that even in our darkest hours, there is still hope. So much has been said and written about 9/11, but I want my son to know and understand its meaning. We weren't New Yorkers that day. I won't pretend we were. But we are now. And he'll hear about my visit to Ground Zero months after the attack and in time, he'll visit the memorial again when he's older and capable of remembering the Survivor Tree and the Twin Towers' footprints. But even still, like so many other children his age and those who either weren't born yet or old enough to remember, he won't truly understand what New York lost that day. In a way, neither will I. Standing at the edge of the memorial that signified where the South Tower stood, I realized I'd never truly understand.

Fifteen years ago, I got back on the bus, wiped away tears and held my best friend's hand tighter. I looked up at the bus driver and caught his kind glance — a moment I'll forever hold in my heart. He asked if I was OK. I said yes, and asked him the same. He looked at me and said,

No, my dear. But we will be. We're New Yorkers.

It's been 15 years since my first visit, and unsurprisingly, so much has changed since then. I leave work now and hustle to catch the subway to my new home in Brooklyn, watching the city move all around me as my son laughs and makes funny faces and waves at random strangers. New York did endure. My son may not have been alive to see the Towers fall or fully comprehend all that occurred on September 11, but he'll grow up knowing a New York that thrives around its darkest hour. He'll grow up to be part of New York that did endure.