Parenting

When The Class Biter Is Your Son

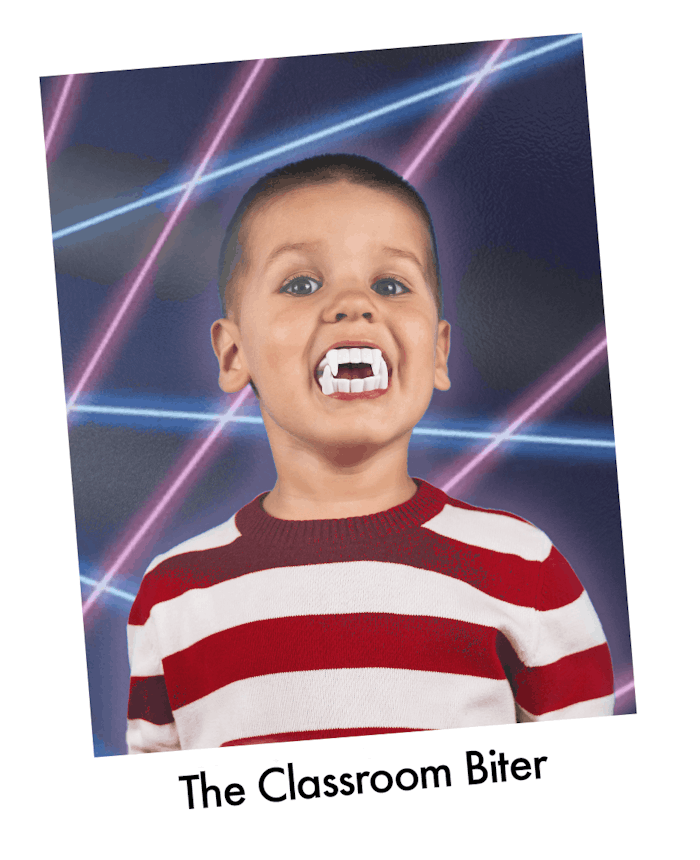

My son had just turned 2 when he developed a taste for human flesh.

My son had just turned 2 when he developed a taste for human flesh.

“Everything’s fine,” his preschool teacher blurted at the start of that first call. I think there must be an expectation that good parents fly into an immediate state of panic at the sight of their child’s school on caller ID. But she was light-hearted. “It happens! Lots of kids bite.” And we laughed because kids are weird and funny like that. But over the course of the semester, the calls kept coming. First weekly, then almost daily.

His teacher would still begin with a dutiful “Everything’s fine!” but with each call, her pitch got a little higher, the tone a bit more tense. Two months into the spring semester, it was official: My child was the class biter.

I think it’s worth noting that this isn’t my first trip around the proverbial playground. I have a daughter who’s four and a half years older than my son and she has never bitten anyone, not once, not ever. In fact, I can’t conjure up a single instance when she’s so much as misbehaved at school. Honestly, I probably felt pretty smug about it, too. But, hey, nothing will wipe that cocksure grin off your face quite as quickly as your kid turning into the real-life version of Baby Shark.

We did all the things recommended to address biting behaviors. We read books. We gave him a pep talk each morning. We sent chew toys and extra snacks. We made sure he got enough sleep. If you’ve never experienced having the “problem child,” let me summarize the experience for you: It’s not fun. It’s embarrassing, shameful, and confidence destroying. All of these feelings were exacerbated by the school’s privacy policy, which forbade the teacher from disclosing the names of any of my son’s victims. I could understand why the school would want to protect Colin’s identity given that he was the one who was out of line, but I could never fully grasp why they wouldn’t tell me who he’d bitten.

His teachers insisted he was the jolliest little biter around. But that isn’t how he was being perceived.

This became a bigger issue when I learned that at least twice, parents had been present to witness Colin bite their children at pickup. That meant they knew who he was, but I still wasn’t allowed to know who the kids who’d found themselves at the business end of Colin’s teeth were. I wanted the opportunity to apologize, to explain myself, to tell them we were working hard to address the problem. I worried the silence on my part would read as callousness, and I felt the silence on theirs as judgment.

My worst fears came to fruition when one of Colin’s preschool teachers let slip that a mother from Colin’s class was campaigning to get him kicked out of school. I was crushed. It was bad enough Colin’s biting felt like an indictment on my mothering, but it was worse that, to others, it was becoming the single defining attribute of his personality.

No one could see the little boy who told me I looked “so pretty” first thing each morning or the one who tried to share his apple with our puppy or sang songs from Oliver Twist or built block towers only to cover his own eyes before exclaiming “da-ta!” Colin was and is incredibly sweet, and strangely, he never even seemed to bite out of anger but instead some sort of lightning-quick impulse he couldn’t control. His teachers insisted he was the jolliest little biter around.

But that isn’t how he was being perceived. And it felt like the fact that he was a boy rendered the situation more fraught. Though he was indiscriminate in his biting, I worried extra when he bit a girl. I swear, never once did I think to myself during that time “Boys will be boys!” But the undercurrents were there. The idea that my son might be some type of origin story for predatory, non-consent-seeking adult men made me want to take up residence in some remote female commune where maybe everyone is naked and no one can find me.

I can’t tell you the number of times I considered how I would have much preferred my son to be the bitee than the biter. How, even after I was screening at least half the school’s calls, I thrilled at the occasional one during which his teacher might tell me he’d bumped his head or tripped and fallen. Even the time she called to break the news that he’d walked in front of the swings and come out with a black eye, I believe my mortifyingly inappropriate reaction was something along the lines of “Oh, thank God.”

Hearing “it’s only a phase” or “it goes by so fast” feels a bit like telling a marathon runner in the middle of a race — it’s only four hours of your life!

By the time we were nearing the end of the school year, Colin’s biting was living rent-free in every corner of my brain. I make my living as a writer and I was contracted to write my next novel as soon as possible, so something sucking up my mental energy could have been a major problem. It would have been, had I not landed on a weird, related idea: A class of preschoolers develops an unsettling medical condition that causes them to crave blood. Not exactly difficult to trace the inspiration from there to here, is it? The premise developed into Cutting Teeth, a book about a group of mothers at Little Academy who are on personal quests to reclaim aspects of their identities subsumed by motherhood — their careers, their sex lives, their bodies — when their adorable children become tiny “vampires” and disrupt their plans. Then, a young teacher is found dead, and the only potential witnesses (and suspects) are the ten 4-year-olds. It soon becomes clear that the children are not just witnesses, but also suspects… and so are their mothers.

Biting became, for me, an apt device to explore the standards society holds mothers to — along with the ones to which we hold ourselves — and the things no one tells you about becoming a parent. Kids really can bleed you dry, and hearing “it’s only a phase” or “it goes by so fast” feels a bit like telling a marathon runner in the middle of a race — it’s only four hours of your life!

It also became a story about parenting in community, about how I’ve come to believe we’re never as good of parents as we purport to be nor as bad of ones as we believe ourselves to be. I think often about that mother who was trying to get my son kicked out of school. Mostly, I get it, I do. She wanted to protect her daughter and was trying to do what she thought was right — in this often thankless, challenging, and at times terrifying career we’re in as parents, we crave the elusive feeling that we’re doing our job and we’re doing it well. The sticky, quagmire of doing good parenting work with a difficult child is a less clear and direct path to the dopamine hit of validation. But it might be more satisfying.

Since that school year ended, Colin has never bitten again. Like magic, he went through his entire year in the “threes” at the same preschool without incident. He was, however, the recipient of one or two bites, and I was delighted for the opportunity to be extremely gracious about the whole thing. There’s a common piece of advice given to authors that goes “You shouldn’t believe your good reviews because then you also have to believe the bad ones.” I think that applies to parenting, too.

The experience of parenting him through that year put me at odds with the other mothers at his school, but in the end, led me to write this book that’s already helped me connect with so many other parents through our various triumphs and failures. I dedicated Cutting Teeth to Colin.

Though his taste for human flesh has faded, my love for him will never.

Chandler Baker lives in Austin with her husband and toddler, where she also works as a corporate attorney. She is the author of several young adult novels, and her adult debut, Whisper Network, was a New York Times bestseller and Reese's Book Club pick. The Husbands was a USA Today bestseller and a Good Morning America Book Club pick. Cutting Teeth is her third novel for adults.

This article was originally published on