the way we live now

Nothing Brings You Closer To Your Phone Than Pregnancy

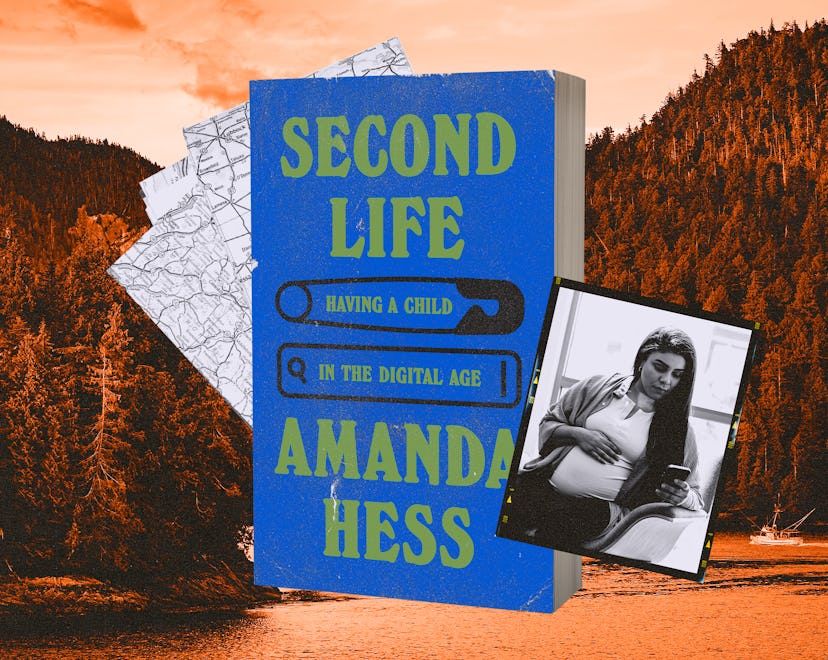

In her new book Second Life, Amanda Hess charts the emotional experience of parenthood, mediated through our screens.

As critic-at-large for The New York Times, Amanda Hess is no stranger to a strong opinion and clear conclusion. But in her first book, Second Life, she joins the rest of us in the sleepless struggle to find the best (or best for us) way to step into the role of parent for the first time in a technology-saturated world. But medical complexity complicated Hess’ process even more: Far into her pregnancy, her son was diagnosed with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), a rare congenital condition with varying outcomes, often characterized as an “overgrowth disorder.”

Part memoir, part tech reportage, part cultural criticism, and no parts parenting how-to, Second Life is an evocative glimpse into the anxious swirl of pregnancy and the early days of first-time parenting. It’s also a sobering exploration into how tech companies are offering answers where there may be none. Hess allows us to sit beside her as she dives into her phone, tech history, and medical and anti-medical message boards, to better understand her son, herself, and the digital world we’re all swimming in. We spoke about all this and more over Zoom one warm Friday afternoon from our respective bedrooms on either side of the country — me in San Francisco and Hess in Brooklyn.

Second Life is such a unique addition to the parenting book landscape. What kind of book did you set out to write, and why?

I had an idea a few years ago that I wanted to write a nonfiction book where technology played the role of a character. At the time, I didn’t know what that meant. But when I got pregnant, I immediately realized that I was forging a newly intimate relationship with my phone. I knew that it’s completely natural to grow a human inside your body, but I’d never done it before, and it was very alarming to me, so I was seeking reassurance everywhere I could — but not talking to people about it, especially at first. So I started taking notes and screenshots of the things that I was seeing.

Then later in my pregnancy, when it became complex, I had this horrible, superstitious feeling that by writing down funny anecdotes about my pregnancy, I had done something. So at that point, I forgot about the idea of a book. Then a few months later, I started to think that this superstitious feeling — which is not a feeling I typically have — was interesting, and all the other feelings of self-blame and shame that came along with that were too. I decided that I should actually write about that experience.

I also wanted to illuminate the larger structure that I was operating in, and the histories and ideologies that were being cycled through it. I know that some people want to read advice, but I barely know how to parent my own children, much less advise any other person on how to do that. I don’t have an answer for what we should do about all this stuff. For me, by better understanding the conditions under which technologies are made and the histories that they’re drawing from, I can demystify them, and they just turn into plastic and wires again.

Screens mediate so much of parenting life in your book — the phone, of course, but also monitoring devices and medical technology around your son’s diagnosis. Screens are access points, portals and interpreters during pregnancy and the early baby days. I’m curious now that both of your sons are older, is that mediation still an experience you’re having?

The time when it was most intense was when I was pregnant. Technology gave me my only relationship with my son other than this feeling of him moving inside me. One of the things that I wanted to write about was how much the images and expectations that I had built about what my son would be like were challenged by his actual personhood when he arrived. During pregnancy, I was using the Internet to try to assert intellectual control over the situation — like if I just had all the information, I’d be able to handle it.

I felt like by googling images of kids who have BWS, and googling online reactions to those children, I could understand what society really thought about my child. I think there’s an extent to which that’s true and an extent to which it’s not, and it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that I stopped using social media so much after my first son was born.

Can you imagine a different way for you to have had your pregnancy or the early baby days — or for other parents to? What’s the alternative to staring at the screen and collecting information?

I’ve found it really clarifying to stare at other stuff on my screen. Signing up for mutual aid WhatsApp groups or Slacks gives me the constant updates that my brain is wired to want. But the updates are about needs in our community and trying to find people who can fill them, as opposed to updates that create a false need for my family that I can fill by buying something. So it’s not that I necessarily use my phone less, but it’s been good to seed it with more positive habits and community.

Is there any new technology around kids that you’re looking at now, either as a reporter or a parent?

A lot of my book is about prenatal medical technologies, and for me, the problem is not that we have too many prenatal technologies or that they’re advancing too quickly. I think the problem is there’s so much investment into these technologies and so little in actually making our society accessible for disabled people and a good place to live for everyone. There’s not enough funding for medical research for humans who actually exist. I fear that because these prenatal technologies are being developed in a context that is increasingly anti-medical and where inequality is becoming so vast that this reproductive access gap is getting wider and wider, and that scares me. So it’s less about if a particular genetic test should be developed or not. I am worried about there being a really poor context for what’s happening.

Early parenting can be so lonely already, but you had your first son in the throes of the Covid pandemic, too. Since then, have you found new forms of community online, like in those mutual aid messaging groups, or in real life?

After I had my first son, there was a Covid vaccine, so that made things a lot easier! I had many friends who had kids at the same time that I did, but for a while, we were not going into each other’s homes, and older relatives were not coming into our home. Just that change has been such a relief. But also as my kids get older, they are finding their own community. I feel uncomfortable with this construction of myself as a capital-M Mother — an identity that exists somewhere outside of my personal relationship with my kids. When they choose their friends and favorite activities that takes the pressure off of me being the one who makes those kinds of decisions.

You once wrote an essay for Slate that’s still online about how you were opting out of kids, and now you’ve written a book about having them. How do you make sense of that division of selves — even if this one isn’t that comfortable with the label of capital-M “Mother”?

I think the more honest version of that essay that existed inside of me at the time was “Maybe, but I’m never going to meet someone who is going to be an equal partner, blah blah blah. I can’t imagine my life circumstances aligning in all those ways.” I think there’s a sense in which I’m glad I wasn’t worried about having kids as a young woman, because I was just living my life. But at the same time, I do think I was missing the structure of intergenerational community. If I had had that when I was in my 20s, I would not have been so freaked out about being pregnant and taking care of a newborn. Maybe I would have changed a diaper already! And if I’d felt like I was living in a community that had more structures of communal care, maybe I would have thought differently about when to have kids or if to have kids. I don’t know. I still feel like if pre-kids me saw myself now, she’d be like, “Wow, you wrote a book that’s so cool. But it’s about parenting?!” I don’t think she’d think that was cool. She lives inside me somewhere, but she’s not here now.

You write in the book about how this can be a very unique — and uniquely hard — moment to be a parent in part because of technology. But you also went back and looked at old parenting books that had bits of the same advice that’s out there today and considered how parenting has always been so hard. I’m curious where you land now: Is it tougher now to be a parent?

I think it’s so hard for me to understand anything outside of my particular experience. People talk a lot about how our society is more atomized now and it’s harder to draw on community and family help. Families are smaller. Grandparents are older. Everybody’s working. There’s not a one-income middle-class family anymore.

Definitely, those kinds of comparisons make it feel more difficult. But then I read a Dr. Spock book from the 1940s, and see all of the childhood illnesses that they had to deal with that have been eradicated in the United States — although I guess we’ll see if they come back now. Especially for anyone who’s in any way not a wealthy white man, every other era of history was really, really difficult, and of course, so is this one.

As for technology — when I go back and read parts of Guy Debord’s The Society and the Spectacle, which was written in the 1960s, I’m like, “Oh, this guy’s talking about right now.” So it’s not as if the dynamics of this mediation are completely new. But I do think it’s difficult to understand what technology would be like if it were not developed for profit. I see technology, and particularly social media, as functioning within a capitalist system. We need to be forced to be more productive and conditioned to buy more things, and the speed is always increasing. Maybe it feels the same way as when television started — I don’t know. But I think if I threw my phone into the ocean, it wouldn’t solve my problems. And if we all threw our phones into the ocean, they would just come up with something else. Technology is the way in which this system is sold and justifies itself now, but it’s not the root of the problem.