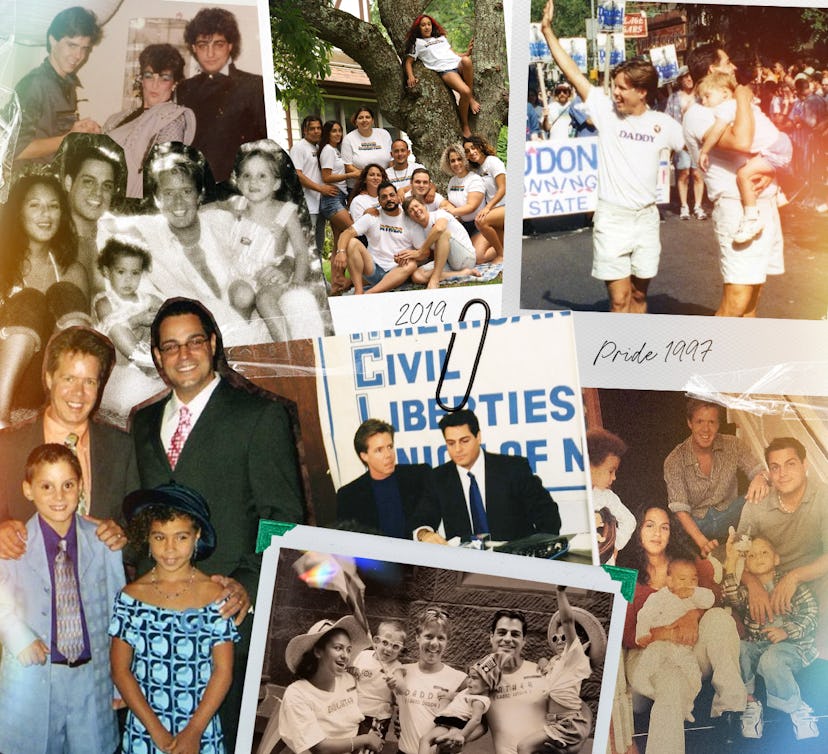

PRIDE

In 1997, My Uncles Became Parents & Paved The Way For Queer Families Everywhere

Uncle Michael and Uncle Jon were always there, but the laws that allowed them to adopt my cousins were not.

I’ve never lived in a world where “Uncle Michael and Uncle Jon” didn’t exist. Michael is my mother’s older brother, and Jon is… Uncle Jon. For as long as I can remember, he’s been everywhere Michael was: every holiday, milestone, backyard cookout, and Sunday dinner. As a child, I loved visiting them because their home was always superbly decorated, a cross between Alice in Wonderland and the ballroom scene in The Labyrinth. They’re witty, stylish, and always give the best Christmas presents. (We’re talking an American Girl doll, people!)

“Do you think Uncle Michael will ever get married?” my brother asked me one day when we were about 12 and 9. He seemed almost wistful. “Uncle Michael is gay, Scott,” I retorted. “Uncle Jon isn’t just his friend.” I said this in a tone that was half-condescending, half-pitying. A tone that said ‘You simple, sweet child.’ A tone that in no way indicated I’d just realized that myself maybe a month earlier. This was 1995, a full two decades before Obergefell v. Hodges. Within a year or two, Uncle Michael and Uncle Jon’s relationship would be a national news story.

Depending on who you ask or what you put into Google, the first “gay adoption” in the United States could be attributed to any number of people. Reverend John Kuiper of New York is often touted as “the first” gay man to adopt a child in 1979. But when Bill Jones adopted a child in California in 1968, papers mention he was “among the first” nationally. There’s a reason for the confusion: historically, adoptions by LGBTQ+ parents have been handled quietly.

Couples and individuals have shied from drawing too much attention to themselves lest they face discrimination or, worse, have their adoption petitions denied. The complete story of queer adoption in America is lost to history. But part of that history lies with Uncle Michael and Uncle Jon, who were the lead plaintiffs in a case that made New Jersey the first state to explicitly grant unmarried couples the right to jointly adopt, opening the door for same-sex partners in the state, and eventually the country, to start families.

~

The two met at a party at Michael’s frat house in 1982. Jon decided to pledge. Within six weeks, Michael was talking “forever.”

“Think about our family in 1982,” he tells me. (I do: loving and extremely tight-knit, but even more so extremely Italian. Catholic, traditional, and very preoccupied with keeping up appearances.) “If that was going to be my direction, I was gonna lose everything, so it had better be forever.”

There’s so much, for the sake of space, that I have to skip that happened over the course of the next decade: coming out, trauma, death threats, moving away, family tragedy, and coming back home — all culminating in an uneasy peace within my family: Jon was accepted and welcomed under the unspoken but clear condition that the nature of their relationship was never discussed. Even my mom, whom my uncles describe as their most steadfast ally, never broached the subject with me or my siblings. Even after the pair unofficially married on their 10th anniversary.

“For me, it wasn’t anything I ever broached because it just was. I didn’t really feel the need to say anything that you weren’t observing for yourselves,” she says. “It never even occurred to me that you guys would see them as anything other than a couple. It really did take me by surprise. Your dad, too! He was so upset I didn’t tell him Michael was gay. But to me, it would have been like me saying ‘I’m straight.’”

By the early ’90s, both realized that for their relationship to continue, Jon needed to seek help getting sober. He worked a program and the pair went to therapy, both as a couple and individually, where they began to “challenge internal homophobia.”

“During that whole process, we started having really heavy conversations, which was where we came to the realization that we both really regretted the part about being gay meaning that we could never have kids,” says Michael. The subject, which they’d privately lamented together, came up again one night over dinner with friends.

These friends just so happened to be a gay couple and their two adopted sons.

“One of them, who was a gigantic blonde Viking man, leans over on the table and goes, ‘Why not?’” Michael recalls. “There was literally a gay family staring us in the face. And once it was said out loud, there it was. There was no stopping it.”

It was the room of a child who was already loved tremendously by parents who wanted every beautiful thing for him, before they even knew who he was.

Jon did all the research (which Michael attributes to Jon’s career being more flexible, but it’s really because of course Jon was going to do all the research). They knew from the jump that they wanted to pursue “foster to adopt,” and worked to become accredited foster parents in the state of New Jersey’s Division of Youth and Family Services (DYFS, now called Department of Children and Families or DCF).

“There was a sense that we had to be perfect,” Jon recalls. “We did everything in our power to be the best. It wasn’t enough to pass the trainings: we had to be number one in the class. We were going to have the best references. If we had to get it from the Pope, we’d get it.”

In December of 1995, days before Christmas, they got the call: there was a medically fragile 3-month-old boy available for placement. “He became our son the second we met him,” Michael says. “No question.” Within a week, Adam (whose name is an acronym for Michael and Jon’s parents, Adolf, Dorothy, and Ann Mary) had moved into the nursery they’d had prepared for months: a dark green carpet to represent grass below sky-blue walls complete with a mural of a rainbow and fluffy white clouds. I remember this room so clearly because this was in the days before Instagram-perfect nurseries were the norm; it was the room of a child who was already loved tremendously by parents who wanted every beautiful thing for him, before they even knew who he was.

At the time, there was a standard procedure for same-sex adoptions in the state called “second-parent adoption.” It goes like this: one parent adopts first. Their partner then applies for what’s known as “second-parent adoption,” which allows a second parent to adopt their partner’s child without the “first parent” losing any of their rights. But this means adoptions cost same-sex couples twice as much and, between that first and second adoption, if something happens to the first parent the second parent has no legal rights to their own child. (To this day, this is how many states enact same-sex adoptions.)

That was not going to work for them, which they told DYFS. They wanted a joint adoption: the kind that would be granted to them if they were a married, heterosexual couple. DYFS said that wouldn’t be a problem… until there was a problem.

Months after the placement, Jon got the call: the law stated that unmarried couples couldn’t jointly adopt. They would have to pursue second-parent adoption, and because Jon had no income as a stay-at-home parent, Michael would be Adam’s only legal parent until Jon’s second adoption could go through.

They were initially at odds on how to move forward. Michael, like generations of gay adopters before him, didn’t want to make waves and risk losing their son. He was inclined to follow the status quo, even though he knew it was unjust. But for Jon, the status quo meant that the risk of losing Adam was ever-present.

Eventually, they agreed: the law needed to be challenged, and, with some trepidation, they accepted the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)’s offer to defend them as lead plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit to sue the state for the right of unmarried couples to adopt.

It was around this time that Jon got another phone call: there was a 3-month-old girl who needed a placement.

“I was in the other room dressing down the ACLU in a particularly heated moment,” Michael says. “I took a moment and went into the other room and Jon’s in my face saying, ‘Honey… it’s a girl.’”

“By then I made up my mind that this is our girl and now I had to sell Michael in the middle of all of this,” Jon laughs. “Finally I said ‘The ACLU is in the other room. We’re getting ready to sue the state of New Jersey. They are never going to give us another baby. This is our last chance. It’s yes or no right now.’”

That’s how Madison (named after a drag queen they’d met a few months earlier, naturally) came to live with them in March of 1997. And with Madison, came Rosa.

Rosa, a teenager at the time, is Madison’s biological sister. After finding Michael and Jon, she asked if she could visit with the baby “to say goodbye at just one last visit.” But, as Jon laughs, “We don’t do ‘just one’ anything in this family.”

By August, Rosa was living with Michael and Jon as well. (For me, who’d never had a cousin her own age, I was over the moon.) In less than two years they’d gone from desperately wanting a child to having two children under 2 and a teenager — but until adoption could take place, permanence was never guaranteed.

Adoptions, regardless of who is pursuing them, must go through the courts. Judges are asked to rule in “the best interest of the child.” Following a special petition to the court, Adam was formally adopted, jointly, in October 1997. But the judge’s ruling was so narrow that it did nothing to change the unfair law or even ensure Madison and Rosa’s adoptions.

Finally, in December of that year, Michael and Jon, along with a cadre of 200 unmarried couples, mostly gay and lesbian, won a legal battle against DYFS, making New Jersey the first state in the country to allow unmarried couples, including same-sex couples, to adopt a child together. No need to pursue a second adoption. No special petitions required to secure the same treatment straight couples enjoyed as a matter of course.

The law didn’t and doesn’t automatically grant adoption rights to everyone — to this day, adoptions are at the discretion of a judge — but it forbids the state from denying an adoption based on marital status or sexual orientation of the prospective parents. Queer couples, in other words, must be judged the same as heterosexual parents: there would be no more double standards. So while some, perhaps many, gay couples had been able to adopt jointly before them, Michael and Jon’s case with the ACLU made it so that, for the first time, the law was straightforward and equally applied to all.

It’s a moment my cousin Adam, now 27, recently swore to me he remembers. “My strongest memory is sitting there with a water bottle in my mouth when my parents were on the news and Michael Adams [the lead ACLU lawyer on the case] was speaking,” he said. I feel the need to point out that there’s a photo, famous in our family, of Adam as a toddler gnawing on a water bottle during a press conference. “You were just a baby,” I tell him. “I actually remember that!” he insists. (I can practically hear his sister and fiercest protector, Madison, lovingly roll her eyes in the background.)

“Are you proud of everything your parents did to adopt you?” I ask.

“No,” he deadpans, then chuckles — Adam is a funny guy, but no one finds Adam funnier than Adam. “Yes, I’m proud of my parents. I’m a part of a family that loves me and supports me and is there for me all the time and that’s what matters.”

“This was the first time that the world was having this conversation. There was no real precedent.”

The media took notice, and the case became a way to talk about the subject of gay and lesbian adoption more generally. Most stories, whether in print, radio, or television, followed a familiar pattern.

- Look at these adorable children… but this family is different. This family has two dads!

- That’s right, two dads! Boy, it sure is progressive and wacky here in the ’90s.

- *Insert inevitable line about Adam’s birth mother being a “drug-addicted woman who was infected with the AIDS virus.” (This was strictly speaking true, but Jon and Michael believe this was a misguided way to make them appear to be sympathetic saviors.)*

- But not everyone thinks this is OK! Let’s hear what this prominent bigot has to say about it.

- *Insert bigoted statement here.*

- *Insert a heartfelt rebuttal from Michael and/or Jon.*

- Well, one thing’s for certain: whether you like it or not, American families sure do look different now!

“In retrospect, the coverage probably should have been a little different,” Jon muses, noting that every interview had to have “an anti.” In one case, it was the late Reverend Jerry Falwell on Larry King Live. “But I think this was the first time that the world was having this conversation. There was no real precedent.”

Lawmakers paid attention, too. Prior to the class-action suit in New Jersey, only Florida and New Hampshire had laws on the books regarding same-sex adoption. (Specifically that it was not allowed.) In the coming months and years, all states clarified their position on the subject… which isn’t to say the clarification has always skewed toward progress. Even today, post-Obergefell, laws pertaining to same-sex and queer parenting vary wildly from state to state. A majority of states (32, in fact) don’t even guarantee second-parent adoptions. Twelve states specifically have laws discriminating against queer couples. A 2015 federal bill that would have banned such discrimination throughout the country — the Every Child Deserves A Family Act sponsored by New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand — has never moved past introduction.

~

Since winning their case and, legally, starting their family, Michael and Jon have lived in three states and half a dozen towns. They’ve been involved in local politics and continue to speak at dinners, rallies, and other events, sharing their story and promoting LGBTQ+ rights alongside their children. They were especially involved in the fight for marriage equality, getting married multiple times wherever and whenever the law permitted them to be husbands. In 2012, they spoke before the New Jersey state legislature alongside Madison and my grandfather.

Despite the ongoing rhetorical opposition to the idea of same-sex parents, their communities have all been warm and welcoming.

“There's a lot of power in being comfortable in your authentic self, and that’s something therapy gave us,” Michael says. “Ever since then, we have been our authentic selves, always. We’ve definitely experienced ugly people in the media, and we got emailed a death threat once, but everything negative was always ‘out there.’ Among people who actually know us, they’ve only ever accepted who we are.”

It’s a feeling echoed by their daughter, Madison, now 26. “Growing up I thought there were going to be more people being weird about the fact that I had two dads,” she pauses, “But I guess not because it was my generation that I was talking to and literally every time I moved to a new school or I met somebody around my age it was like, ‘Oh my God, you have two dads? That’s so cool. That’s amazing! I can’t wait to come over and meet them.’”

And for as long as she can remember, she was not only willing but eager to join her parents in continuing to push for fairer laws for LGBTQ+ communities. “I was born into this story — I grew up knowing, ‘This is what we did to adopt you’ — so I think I’m just a born activist,” she tells me. “We’re proud of who we are. If someone didn’t like it, who cares, but if they were trying to interrupt our daily lives then we’re going to go out and fight. Like, ‘OK. I’m ready, let’s go. When I got married, I felt like it was happening because of what we did. We really fought for that.”

In addition to Madison’s wife, Precious, the family now includes Rosa’s husband, Jose, and three granddaughters (all Rosa’s), Marianna, Leila, and Joselyn. The only baby in the house now is Henri, their puppy, and if you ever want to know what kind of parent Uncle Jon was to his children, you just need to watch him interact with this tiny dog for about three minutes. Despite a rocky start 40 years ago, Michael, Jon, and Adam are living under the same roof as my grandparents.

Now that their kids are older, they do the kind of things any couple that’s been together for 40 years would do: they travel when they can, they garden, they go antiquing. More than 40 years ago, Michael said forever, and Jon confesses that he was skeptical.

“I didn't believe in forever at all. I came from a broken family and had no visual of what forever looked like,” he says. “So I was like, ‘Yeah, OK.’ Because it was hot.” We laugh. “It was a while before I said, ‘OK, I believe in forever, too.’”