rejection

The Three Long Years When My Baby Hated Me

Precisely when we finished weaning, her parental preference shifted dramatically, and in favor of my husband.

When my daughter—my first; my only child—was 8 months old, I stopped breastfeeding. The decision appeared to be mutual; it exhausted me and brought on a strange and persistent nausea, and, anyhow, my daughter seemed to prefer the bottle and formula. She never made a gesture for my breast again. Precisely when we finished weaning, though, her parental preference shifted dramatically, and in favor of my husband.

The preference would’ve been fine — refreshing, even — if it had stayed in the realm of wanting him to hold and feed her, but this was a complete refusal of my care of any kind.

When I was the one who prepared her food, she’d throw it on the ground. When I tried to change her diaper, she’d kick her legs and scream for Papa. When I went to retrieve her from the crib, she’d prostrate herself on the mattress and fall through my grasp. All day, she shouted, No Mama no; Papa do it! No Mama no; Papa do it!

Papa couldn’t always do it, and we didn’t always want to give in to her demand even when he could. I kept preparing her food, changing her diaper, trying to lift her from the crib — and the revolt only increased in intensity.

(Years later, in our first parent-teacher conference, her teacher tells us: Your daughter is what we’d call ‘very spirited.’ Oh yes, we said. We are aware.)

If my daughter preferred me over my husband, there’d be no story here. That is what is expected in a mother-father family.

We read many articles online, listened to many podcasts, consulted our pediatrician, and tried all the strategies they advised. By way of comfort, they all said essentially the same thing. “Favoritism does not equate to being a better parent or more loved,” says pediatrician Dr. Deanna Barry. “It might not be about favoritism per se but more about your child wanting to have a say or get things done their way.” Demonstrating a strong preference could even be a good sign of healthy development and attachment. “If a child feels comfortable actively rejecting one parent,” says Dr. Nia Heard-Garris, M.D., in The New York Times, “that means she’s securely attached … Being able to reject a parent means that a child knows the love is unconditional.”

I was relieved by the high frequency of the words normal, healthy, temporary — all balms for any unnerved parent. But still: nothing worked.

If my daughter preferred me over my husband, there’d be no story here. That is what is expected in a mother-father family. Mom gets the brunt of the boundary-testing behavior—but she is also the one who can best comfort the child; she is preferred, primary. I was certainly getting the brunt, but I was not the comfort object. My daughter and I defied archetypes in part because our family tried to defy traditional roles; for most of my daughter’s life, my husband and I both worked from home. With no day care available, we had to be meticulous about our child care shifts. A chart hung on the fridge, color-coded for every hour in the week.

We were as equal as we could get, in that way. Our parenting styles were very aligned, as well; one was not lenient where the other was harsh. There was no primary parent — or not until my husband started a new job.

The job was good — it offered more money, more stability, and health insurance, at last! — but it wouldn’t be as flexible. My job as a psychotherapist was easier to shift up and down, and so I shifted it down. I was about to become the primary parent, and my daughter couldn’t stand to share a room with me. It was about to be hell for all parties; something had to change; we needed help.

I made some calls, and I got through to one family services clinic recommended by a friend. After describing to the intake coordinator the issue, and all the tactics we’d already tried, she asked, What is your child’s insurance? I was confused, thinking it’d be billed under my insurance.

Since your daughter is the one with the problem, she said, it’s her behavior we want to correct. So she is the patient.

I felt quite certain that nobody was doing anything wrong, something just wasn’t right.

When the clinic called back to say they finally had an opening, I didn’t return the call. Nothing had improved — those first weeks of my husband’s new job were every bit as excruciating as I’d predicted — but I kept turning over the words, she is the patient, and I wondered with unease what it’d mean to “correct” her. I felt quite certain that nobody was doing anything wrong, something just wasn’t right.

My husband’s new job was virtual, which meant my daughter banging on his office door all day. With no good place for him to work in public, we went out.

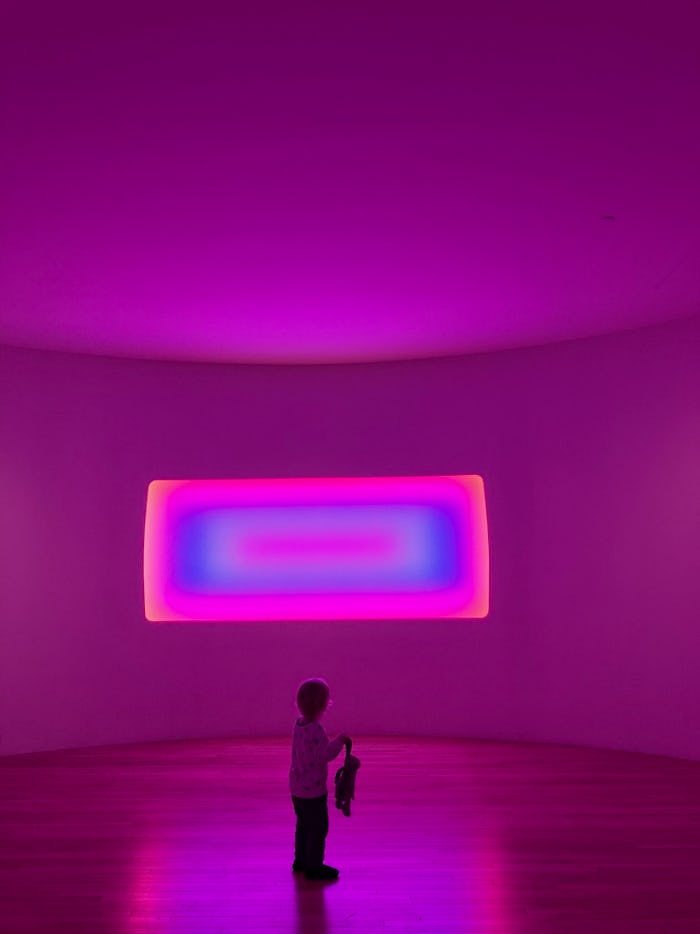

I began taking her to Mass MoCA, a contemporary art museum in the Berkshires, 30 minutes from our home. The museum is enormous, an old printing cloth factory, a place we could be for hours and hours. We began going several times a week together, co-constructing a routine. We had our own order of exhibits, starting with Armando Guadalupe Cortés on the first floor, and ending with running in circles inside James Turrell’s silo outside. We had our table in the kid’s space by the window, and the table in the cafe by the window. In one Laurie Anderson installation, we lay on the floor on our stomachs in a very dark room and watched the light move across the walls.

There were many tantrums in the gift shop, many irritated glances from arty passersby, and many times I was certain she was going to destroy an exhibit. It was never easy to be there together, and I often returned home with a migraine, one or both of us in tears.

We kept going anyway; this was our place, and we were lucky to have it. Over time, the struggles began to diminish, a little. She was not getting easier — she will never be an easy child, and that is alright — but I was getting better at anticipating when we needed to stop for a snack, and when she was 30 minutes from a meltdown, as opposed to 30 seconds.

One day, she was running through the halls of Sol Lewitt, getting way too close to the paintings, then stopping just in time. When she started to sprint down a ramp, I called for her to slow down; she tripped and fell, and after a moment of shock, she screamed. She didn’t call for me — but she didn’t call for Papa, either. She let me come to her, check for blood, and then she said, I’m fine, Mama, stood on her own, and kept running.

Anna Hogeland is the author of The Long Answer (Riverhead Books). She’s a psychotherapist in private practice, with a master of social work degree from Smith College School for Social Work and a master of fine arts degree from the University of California, Irvine. Her essays have appeared in Literary Hub, Big Issue, iNews, Gloss Magazine, and elsewhere. The Long Answer is her first novel and has been translated into seven languages. She lives in western Massachusetts.