Parenting

The Internet Doesn’t Make Kids Trans — It Just Helps Them Feel Less Alone

The recent attacks on gender diversity are based on absolute pseudoscience, but the worst part is that no one bothered to talk to the kids themselves.

In June of 2021, I met with Katie and her family to talk about their experience of Katie coming out as transgender in a conservative Southern state. Katie was 18 years old and grew up in a small town in Tennessee. When I first met her, she was sitting at her family’s dining room table, leaning so far forward it seemed as if she would curl up into herself. As she moved her wavy blond hair away from her face, her kind brown eyes revealed a hint of sadness. But after a few minutes, once it became clear that I accepted her for who she was (I called her Katie and used she/her pronouns), her posture corrected, and she became vibrant and confident. The sadness in her eyes evaporated into joy, and a new touch of sass accompanied the Southern twang in her voice. We spoke more about her life, and Katie and her mom told me that Katie is a nationally renowned fencer, beloved by her friends and her coach in particular, who, by all accounts, is quick to tell everyone she’s the most talented athlete he has ever worked with.

Katie’s mom, Jillian, is a data scientist, and her dad, Mark, is an executive at a software company. Katie has a younger brother, Kevin, whom she adores. I’m always skeptical when kids say they don’t fight with their siblings, so I pushed the question a little: “You two never fight?” Katie laughed and let me know that they fight about small things, like the TV remote, but that he truly is one of the most important people in her life. He had one of the best reactions when she came out as transgender: He didn’t make a big deal about it. He still just saw her as the sibling he loved (and from whom he would always steal the remote when she went to the bathroom). Katie’s mom shared that Kevin suffers from a rare collagen disease, which required him to be in and out of the hospital for many years when he was younger, putting a strain on the family. He’s now healthy and doing well, but Katie is still very protective of him.

As a researcher and child and adolescent psychiatrist, I've spent over a decade supporting transgender youth and their families, and one of the most striking things about Katie’s family is how open they are. “People sometimes think we’re weird because we don’t fight, but really we just have a philosophy to always say what we think, so disagreements get resolved fast,” Jillian explained.

Even so, for years there was something Katie felt she couldn’t put on the table: She didn’t really feel like a boy. She spent over a decade afraid that if she told her parents or anyone at school, she would be bullied or rejected. And she had good reason. When she was in elementary school, she tried to hold her friend Charles’s hand in the lunch line. She thought it was a nice way to show that she cared about him. But her mother was called into the principal’s office the following day and told that Charles’s family “doesn’t put up with that homosexual stuff” and that Katie wasn’t to be friends with Charles or to go anywhere near him. The message was clear: Conform, or you’ll be in big trouble.

As Katie put it, “I went so far in the closet I was in Narnia.”

It’s sadly a common experience for people to hide or sacrifice who they are in order to fit in, avoid social ostracism, and establish connection. Humans are hardwired to want to affiliate with others. It can be easy to overlook the potential pitfalls of this. Dr. Brené Brown explains it well when she discusses this framework: fitting in means being like others to be accepted, whereas belonging means showing up and saying, “This is who I am. I hope we can make a connection.” This second approach allows for greater self-confidence, less shame, and deeper, more genuine connection. Sadly, many trans kids like Katie aren’t given that option.

Katie has a vivid memory of going to Spirit Halloween with her mom and brother in fourth grade. She remembers walking through the aisles seeing Godzilla heads, vampire fangs, and creepy clown costumes. None of them felt right for her, and if anything, they made her feel scared. Moving through the aisles, she looked down at her feet and hastened past the Scream masks. When she looked up again, she saw a bright orange tutu hanging at the end of the next aisle. She let out a small gasp. It was perfect. She called her mom over to show her. Katie beamed in the car on the way home, the Spirit Halloween bag on her lap overflowing with the tutu and a green Morphsuit (one of those tight bodysuits that covers the whole body).

Fitting in means being like others to be accepted, whereas belonging means showing up and saying, “This is who I am. I hope we can make a connection.”

When she got home, she ran up the stairs to her room to change into her outfit and get ready for a school Halloween party that night. But as she stood in her bedroom doorway, her dad saw her and yelled, “Whoa, whoa, you can’t wear that! People will think you’re trying to be a girl!” Katie’s heart sank into her stomach. It was one of her earliest and most intense experiences of gender threat, and a strong message that the expectation was to “fit in” not “belong,” even within her own family. She looked at her dad for a second, then looked away. She pulled the tutu down, kicked it off her shoes, and didn’t say another word about it. She went to the party in just the Morphsuit, which hid the tears rolling down her bright red cheeks. From that moment on, she vowed to present herself as being as masculine as possible, forcing her voice to sound deeper and throwing herself into sports that people would think were manly, including football and baseball. Over time, she developed the slumped posture I noticed when I first met her, a physical manifestation of her attempts to disappear from public sight. She also became depressed.

In her quest to appear masculine, Katie did find one sport she loved: fencing. For years, Katie’s fencing coach would comment to her mother that Katie had all the skills needed to be the best fencer on the team, but something held her back, and she had never won a match. He always felt she was hiding something, and that whatever it was had made her deeply sad.

At 17, Katie finally came out as transgender. To her surprise, her friends and parents accepted her. It was rocky with her parents at first, but they came around quickly. Katie’s dad doesn’t remember the tutu incident and regrets the way he made his daughter feel as a child. With her secret revealed, Katie’s depression improved and so did her fencing. Her mother told me that with the emotional weight off Katie’s shoulders, she started to win every fencing match (she was still competing on the boys’ team). Her coach was thrilled to see her happy and reaping the rewards of her athletic skill. Katie’s quick to point out that coming out helped her depression dramatically, but she’s still impacted by the years she spent closeted and by seeing attacks on trans people in the media.

While Katie’s friends and family handled her news well, not everyone was pleased. Some aunts and uncles stopped talking to Katie and her parents. Her parents were inundated with questions about what they did to make Katie transgender. Jillian was flooded with accusations that her child’s transgender identity was her “fault.” The time-honored American tradition of parent blaming had begun.

As a society we have a strong tendency to blame mothers for anything going on with their children, even when the “problem” isn’t a real problem, as in Katie’s case.

One of Katie’s therapists told Jillian that Katie probably became transgender because her mother spent so much time taking care of Kevin when he was in and out of the hospital. The therapist refused to talk to Katie about her gender identity, telling her she would identify as a boy again if they just continued to work on her depression. Not surprisingly, given how invalidating that approach is, Katie does not think highly of this therapist and no longer sees him. She’s quick to point out, “He didn’t get my depression any better either.”

Soon after that, Jillian’s neighbor Mark called the house and asked if her kids would help him move some boxes. Wanting to avoid any uncomfortable situations, Jillian told Mark that the kids would be happy to, but that he should know Katie had recently come out as transgender and was now wearing dresses. Mark snapped back, “How could you let your child do that?” He then declined the help and decided to move the boxes himself. At every turn, Jillian felt judged. It seemed everyone thought that Katie’s gender identity was a result of bad parenting and that Jillian was wrong to support her.

Of course, this kind of maternal blame is not unique to questions of gender identity. As a society we have a strong tendency to blame mothers for anything going on with their children, even when the “problem” isn’t a real problem, as in Katie’s case.

When children have meltdowns in grocery stores and airplanes, we always hear people ask, “What is wrong with those parents?” It’s rarely someone’s first instinct to consider that the child’s outburst is from biologically determined ADHD, a medication side effect, or a medical condition. Our default is to point fingers at the parents, and usually the mother.

But why do we always blame moms like Jillian when it comes to a child’s mental health or behavior? Psychiatry has likely played a major role here. The field has historically blamed mothers for a wide range of biologically based conditions in their children, from schizophrenia to autism spectrum disorder — to, of course, being transgender. (I intentionally use the word conditions here to highlight that phenomena like gender diversity and autistic traits are often inappropriately pathologized when they are not “issues” but rather healthy variations of the human experience.)

People around Katie and her family were on a desperate search for what in the environment could have caused her to be transgender. They were hardly alone. In 2018, the blaming of social environments for gender diversity was revitalized under a new name: rapid-onset gender dysphoria. Dr. Lisa Littman, an obstetrician-gynecologist researcher at Brown University coined this term in a single-author publication in the scientific journal PLoS One. Sophisticated research studies usually involve a team of researchers, and a single-author research paper is unusual, particularly if the author in question has no prior expertise in the topic.

Dr. Littman reported the results of an anonymous survey of parents she recruited through three websites: 4thwavenow.com, transgendertrend.com, and youthtranscriticalprofessionals.org. 4thwavenow which describes itself as a gathering spot for parents who think their transgender children are not really transgender. Transgendertrend.com, as the name implies, is an organization of parents who similarly believe that transgender children are caught up in a “trend.” The slogan on their website reads, “No child is born in the wrong body.” The third website, youthtranscriticalprofessionals.org, is an organization whose members believe that transgender youth become transgender because of “binges on social media sites.”

Given where the survey respondents were recruited, the results of Dr. Littman’s study were not surprising: These parents overwhelmingly believed that their children identified as transgender all of a sudden and that this identification coincided with their watching videos of transgender people online and linking up with new friends who were LGBTQ. Many of the parents also noted that their children suffered from mental health problems such as depression, and the study suggested that these adolescents’ transgender identities were merely a result of their mental illness. (No logical explanation for why depression would make someone identify as transgender was provided.)

The single most glaring issue with the study was that Dr. Littman did not interview any of the kids. What would they have had to say about their parents’ claims regarding their gender identities?

Based on these surveys, Dr. Littman proposed a new diagnosis: rapid-onset gender dysphoria. She theorized that these children were cisgender, mentally ill, and confused. She suggested that they were influenced by social media and peer pressure that made them believe they were transgender, and that their trans identity was a maladaptive coping mechanism. She went so far as to compare their being transgender to dangerous behaviors some people use to cope, such as anorexia and cutting. It’s worth noting that Dr. Littman had never taken care of transgender patients and, being an obstetrician-gynecologist, is not a mental health professional.

As far as research methodology goes, the study was deeply flawed. All it showed was that parents on websites founded on the idea that social media makes kids transgender believed that social media made their kids transgender. In an interview with the Economist, Dr. Diane Ehrensaft, UCSF psychologist, professor of pediatrics, and a close colleague of mine, stated that Littman’s methodology was akin to “recruiting from Klan or alt-right sites to demonstrate that people who are Black really are an inferior race.”

The single most glaring issue with the study was that Dr. Littman did not interview any of the kids. What would they have had to say about their parents’ claims regarding their gender identities?

When I sat down with Katie and told her about the study, she rolled her eyes: “That’s the most bullshit thing ever.” At that, her mom pushed her thick-rimmed glasses down on her nose and anxiously looked over at me. I assured her that Katie’s swearing was okay — and certainly warranted. Katie explained that she could have easily looked like a kid with “rapid-onset gender dysphoria” to an outside observer but that none of Dr. Littman’s presumptions would have applied.

Katie felt like a girl, but she had never heard the word transgender. Being a girl never seemed like an option, so she repressed her confusing feelings as much as she could.

To Katie’s mom, it had seemed as if her daughter identified as transgender suddenly. Jillian remembers being shocked and thinking, “But you were never girlie. Where is this coming from?” From Jillian’s perspective, it seemed as if Katie’s identity had been “rapid onset.”

Katie had known for many years before officially coming out that she didn’t experience gender the way cisgender kids around her did, but since the tutu incident, she was terrified that people would discover her difference and that she would be harassed and rejected. In her elementary and middle schools, other kids would tease her when she slipped up and did something feminine. If she accidentally revealed that she liked pink, she’d be called a fairy. If she expressed too much natural emotion in drama class, boys would call her homophobic slurs. The hardest part of this for Katie was that she didn’t understand what was going on with herself. She felt like a girl, but she had never heard the word transgender. Being a girl never seemed like an option, so she repressed her confusing feelings as much as she could.

When she entered high school, Katie had a eureka moment. On her first day of study hall, she walked into a crowded classroom. Kids everywhere were talking loudly, and she struggled to find a rickety desk that wasn’t already taken. Through the chaos, she spotted a group of kids, one of whom was a boy sporting pink nail polish. She felt her heart race with excitement, and without thinking, she sat down with those students, who seemed to know one another from middle school (Katie had gone to a different one). They were friendly and introduced themselves to her. She learned that Julia, with her black pixie cut and angular features, was a cisgender lesbian. She liked to wear overalls with one strap hanging over her shoulder and was obsessed with cars. Daniel, who talked nonstop about the national tour of Wicked he had just seen, was gay and cisgender; he was the one with the hot-pink nails. Alex, who wore a Tennessee Titans jersey and looked like a typical football jock, was straight and cisgender and had two moms. The corners of Katie’s mouth curled upward into a smile as she spoke with them. Who were these people?!

With this new group of friends, Katie finally stopped repressing her instincts. She spoke with a naturally higher voice. She admitted to them that she liked “girlie” things. At one point, Alex was talking to Julia about an episode of I Am Jazz he had watched the night before, a TLC show about a young transgender girl. Katie’s ears perked up as she heard about Jazz. Up until that point, the only transgender people she had seen on TV usually played sex workers or murder victims on Law & Order: SVU. For the first time, she was hearing about someone who was like her. Maybe it was possible to be an openly trans person.

Each day when she returned home, she would, in her words, “butch back up” and wouldn’t let her parents know that she was expressing her feminine side at school. Her parents knew she had a new group of LGBTQ friends, but they assumed that Katie was just open-minded and friendly. She had always been a kind kid who wouldn’t judge others.

At home, Katie continued to deepen her voice, avoided feminine activities, and never said a word about gender. So, when she ultimately opened up to her parents years later, it seemed as if it came out of nowhere. Katie remembers walking down to the family room where her parents were playing cards. She felt as if her throat were tied in a knot as she tried to say the words out loud. According to her mom, Katie’s face lost all color and she looked horrified. She finally blurted out, “I think I’m transgender,” and started to cry. Her parents were shocked and didn’t at first know what to say. They told her that they would always love her and that they wanted some time to process.

In the words of Dr. Littman, Katie’s news seemed “rapid onset” to her parents. Katie suspects this would have been even more dramatic for the kids in Littman’s study: “If those kids knew their parents were prone to those kinds of beliefs, they’d be horrified to come out. When you spend years trying to hide something about yourself, you get pretty good at it. Of course their parents wouldn’t have known before the kids wanted them to.” Luckily, Katie’s parents have been supportive. Though it took time for them to process and understand, they are now vocal and enthusiastic advocates for their child.

At home, Katie continued to deepen her voice, avoided feminine activities, and never said a word about gender. So, when she ultimately opened up to her parents years later, it seemed as if it came out of nowhere.

Our research team recently examined this question of how much time generally elapses between transgender people’s coming to understand their gender identity and their telling another person. Analyzing a sample of over 16,000 transgender adults, we found that for people who first came to understand their gender identity in childhood, they didn’t share this with another person for a median of fourteen years.

Over years of coming to understand herself, Katie also started watching videos about being transgender. Her friends played around with gender expression, but they were all cisgender. Daniel liked to paint his nails, but it was clear in his mind that he was a boy. Katie’s new friends loved and accepted her, but they weren’t quite experiencing the same thing as she was. Because there weren’t any out transgender girls in her school, she looked online to better understand herself and find community. Social media had the added bonus of letting her be anonymous, so she didn’t need to worry about being outed. She watched YouTube videos of transgender people talking about their lives and transitioning.

(As a member of the media committee of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, I spend a lot of time thinking about the nuances of how media, and social media in particular, impact young people. For LGBTQ youth who don’t have other LGBTQ youth around them, it can be an important lifeline for forming connection and belonging. However, not all online spaces are appropriately moderated and safe for minors. It’s essential to teach youth about the dangers of talking to strangers online and to make sure their online spaces, and the way they are interacting online, are safe.)

She learned a lot, but she emphasized to me that those videos didn’t “make her” transgender. She sought them out because she wanted to learn more about herself and what being transgender meant. Her new group of friends also didn’t make her transgender, but they provided a space where, for the first time, she felt safe being herself. She was, for the first time, being her authentic self and belonging instead of changing herself for the sake of fitting in to find connection.

As Katie explained to me, she also didn’t become transgender because she was depressed. Rather, she attributes her many years of depression to being afraid that she wouldn’t be accepted for being transgender.

Dr. Littman’s PLoS One survey received a surge of attention. Wall Street Journal columnist Abigail Shrier published an op-ed that uncritically described Dr. Littman’s theories as fact: Kids were becoming transgender due to social media, and it was a mental illness. The Economist ran similar pieces warning people about rapid-onset gender dysphoria. A fringe idea became a full-fledged conspiracy theory.

Meanwhile, every major medical organization said that being transgender wasn’t a mental illness and that gender-affirming care should be made available to adolescents. The American Psychological Association issued a statement outlining that “rapid-onset gender dysphoria” should not be used in clinical or diagnostic applications, given the lack of empirical support for its existence. But political pundits proposed that maybe all these independent medical organizations were just caught up in some sort of “transgender craze.”

The journal editors of PLoS One required Dr. Littman to revise the paper and issue a correction in which she explained that rapid-onset gender dysphoria was a theory rather than an established diagnosis. The correction also highlighted the fact that she had not interviewed any of the children themselves, nor their doctors, to get their views on whether social media and the environment made them transgender.

“If I am depressed or anxious, it’s not because I have issues with my gender identity, but because everyone else does.”

Soon after the 2018 paper was published, due to the scientific issues with the study, Brown University took down its press release about it. This resulted in a media frenzy around “academic censorship” that added fuel to the fire, giving the paper more and more attention. Fox News ran headlines that Brown was “censoring” Littman. Rapid-onset gender dysphoria was even cited in an amicus brief for the Supreme Court case Harris Funeral Homes v. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission, which asked the Supreme Court whether Title VII’s prohibition of discrimination based on sex in the realm of employment should be extended to transgender people. Three sociologists essentially argued that because many transgender people are suffering from rapid-onset gender dysphoria, there is not a legal basis for extending federal employment protections to people who are transgender.

By the time media sources like Scientific American explained that rapid-onset gender dysphoria didn’t have much basis in science, the damage had been done. People around the world were convinced that transgender identity was caused by external social forces. And once again, the implication was that these identities were unacceptable, pathological, and should be “cured.”

Watching this all happen from California, I was relieved that my patients lived in a place where they were more accepted than in others, But hearing powerful politicians say that their identities were just mental illness, even when they knew it wasn’t true, impacted them. It worsened their self-esteem and in many instances their anxiety and depression. With all the rampant stigmatizing language spreading online and in the news, it seemed clear that social structures supporting trans kids weren’t the problem — the problem was the historical, and now growing, social structures attacking trans kids. As one transgender teen in a focus group once told me, “If I am depressed or anxious, it’s likely not because I have issues with my gender identity, but because everyone else does.”

Jack Turban, MD, MHS is a Harvard, Yale, and Stanford-trained child and adolescent psychiatrist and founding director of the Gender Psychiatry Program at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). He is an internationally recognized researcher and clinician whose expertise and research on the mental health of transgender youth have been cited in legislative debates and major federal court cases regarding the civil rights of transgender people in the United States. He is also a frequent contributor to The New York Times, CNN, The Washington Post, Scientific American, and more. He has appeared on numerous programs, including The Daily Show with Trevor Noah and PBS NewsHour.

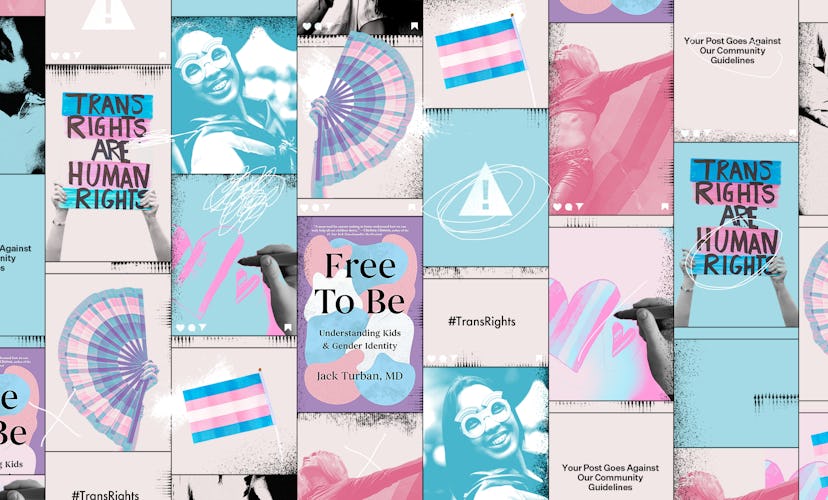

Excerpted from Free to Be: Understanding Kids & Gender Identity, Copyright © 2024 by Jack Turban, MD published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.