Books

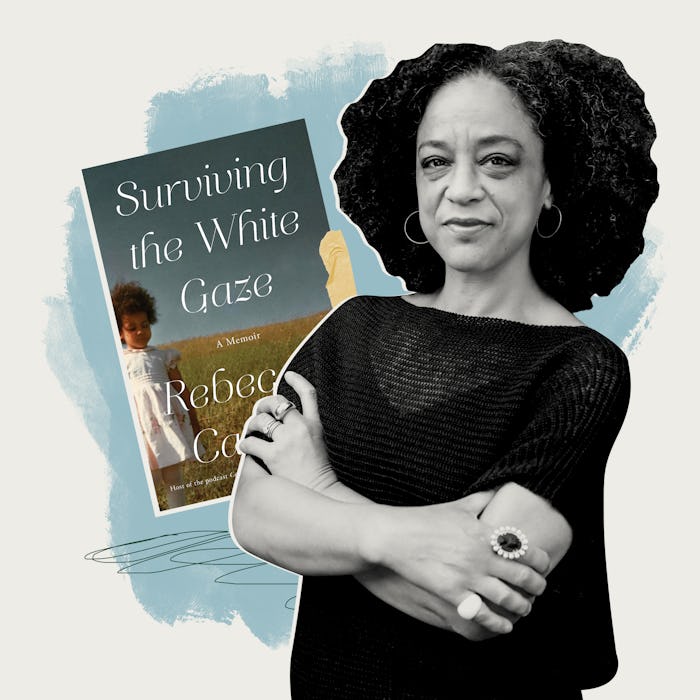

Rebecca Carroll's Memoir, Surviving The White Gaze, Wrestles With The Hard Truths Of Transracial Adoption

"The absence of Black music and Black art and Black people and Black culture in their family is a choice and a value."

There is an enduring myth about parenthood that unconditional love can meet any noncorporeal need a child might have. Pour enough of it into a small person and it can fill any gaps, sustain any psychic hunger. In Surviving the White Gaze, Rebecca Carroll’s fierce, lyrical memoir of growing up the only Black person in her family and in her rural New Hampshire hometown, the writer and cultural critic explores the limits of that notion.

Carroll was adopted at birth by free-thinking artists. They had two children already and wanted a third but believed in “zero population growth.” Rebecca’s teenage birth mother was a friend; they agreed to take in her daughter. “The idea of adopting a child of another race had great appeal for us,” Rebecca’s white father tells her, but race is almost never discussed at home. Her need for connection with other Black people and with Black culture, at first nascent and then more urgent, goes unmet. She is left alone to make sense not only of her difference but of the racism, both explicit and subtle, that she encounters from a very early age.

When Carroll is 11, she meets her birth mother, who is also white. Where her adoptive parents were loving but passive, Tess is a hurricane, pressing her sense of self onto her vulnerable daughter. Hungry for a guide and for connection, Carroll is swept up in her toxic influence.

Surviving the White Gaze is a book about making sense of this influence and of Carroll’s deep longing for her Blackness, which was at first just a whisper and grew more insistent as she found the words to describe it. Her story is a painful reckoning with grief and a joyful account of finding in adulthood what she craved as a child: A deep connection to her Blackness that stretches behind her to her ancestors and before her in her own child.

I spoke to Carroll recently about the fraught process of writing a memoir about family and how important it is to forge a new conversation around the complexities of transracial and interracial adoption.

Elizabeth Angell: I wanted to start by asking when you came to the title and what it means to you.

Rebecca Carroll: Well, I didn't even really know what the white gaze was until I heard Toni Morrison describe it on the Charlie Rose show when I was working there. I was in the control room and I heard her talk about this thing called the white gaze, and I remember thinking, "Wow. That's it. That's the thing that I've been trying to survive and escape and remove and excavate and push out of my body and my brain."

It was truly revelatory. And this was well into my adulthood, right? I started to retrace moments in my life where I could identify the white gaze really doing damage. Because I didn't know how to work against it if I couldn't identify it or pinpoint it because it just seemed so amorphous but also a chokehold of sorts. And that was 20 years ago. But I have, from that point on, started to try to understand the ways that it manifested in my life.

And so I didn't have any sense that that would be the name of my memoir until three or four years ago when I realized that I had arrived at a place where I could write a memoir. And I was thinking about who I've been the most inspired by. It is, of course, Toni Morrison. She made it possible for me to understand what it was that I have survived.

I think that there is more of a willingness to engage in conversations about race and systemic racism than there were four years ago.

EA: What made you ready to write this now, even though you've been writing your whole life?

RC: I realized that I was ready to write it when Michael Brown was shot and I had this conversation with my son and it unleashed this rage in me and this fluency with words that I hadn't had before. It was a combination of writing, mothering, being protective, embracing the endurance and strength that I felt. It was the process of letting these memories live somewhere outside of my body because they didn't need to be with me anymore. There's so much of the relationship with my birth mother that I needed to excavate, just remove it from my brain to the very last strands of scar tissue and just get rid of them. And I feel like that they now live in the book and that's where they belong. I don't need them. They were doing more damage inside my brain and my body.

EA: You began writing this long before COVID and the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, but people are reading it now, in that context. Do you feel that there's a different space for conversations about race right now or for this book in particular?

RC: I do think that we, as a collective nation, are ready to reset. And in that resetting, I think that there is more of a willingness to engage in conversations about race and systemic racism than there were four years ago. What I do in my own work, apart from this book, is to really push the boundaries of what people are willing to talk about. And it's usually that people aren't willing, and I'm trying to push that further. What I really love about the book coming out now is that this story is not just about interracial adoption. Adoptees like me, we actually have extraordinary insight into the dynamic of Black and white America. Whatever the intentions are of the people who choose to adopt Black children, that dynamic is at the center of our country.

EA: What do you mean by that?

RC: I mean, the way that white people respond to — the way they assign identity and value to — Black bodies and people, is how the nation started. That is essentially white gaze and that is the foundation of the country. I'm not at all saying that white adoptive parents can't be good parents to Black children, but unless you are deeply engaged and in constant conversation with yourself as a white parent of a Black child, asking "Am I drawing on that which I have internalized?" Because it’s not going to work for that child.

I hope that with my book, which I’m adapting for television, and with Colin Kaepernick's story coming out, and as other interracial and transracial adoption stories come out, that our voices and our experiences will find their way to these conversations to help recreate language, to help recreate dynamics, as a way to get us out of what we have internalized.

EA: There is an enduring myth that adoption should be colorblind. And from that we get a lot of stories of loving white parents swooping in to rescue an unwanted Black baby from abandonment and poverty. I don't think that particular myth has gotten as much attention this last year, and it’s long overdue.

RC: Yes. I look with great hope and optimism at the ways in which we've been able to move the needle on how we talk about gender, the language we use. I am hoping that we're able to do that in a way we talk about race — and specifically, that dynamic that you're talking about, the assumption that white parents are a better parent than a Black parent would be. And even if white parents of Black children are not cognizant of this idea of the savior complex or they think that they are doing the right thing and they're pure of heart, just the absence of Blackness, it's a choice, right? The absence of Black music and Black art and Black people and Black culture in their family is a choice and a value.

EA: How has having your own child changed things for you?

RC: He's everything, and I am very, very aware of creating a life in which he feels nurtured and welcome to be who he is and to build his identity in ways that I will be here to champion — to fill in questions or respond in ways that I did not have. We reflect each other back to each other, and it's almost impossible to put into words what that means to me. For example, when we were looking for a middle school, I kept saying, "Well, we have to make sure that he goes to a school where you have Black teachers and Black peers." And Kofi was like, "You are so extra about this, Mom." And I came back and said, "Right now, off the dome, name three Black role models in your life." And he said, "Well, Dorlan, Caryn, and you." And it never occurred to me that I would be enough. But that speaks volumes to what I missed. He has changed my life in the most magnificent ways.

EA: Have your parents read the book? Have you talked to them about it?

RC: Well, the answer to that is ongoing. When I finished the final manuscript, I offered my father a chance to read it and he declined. And that hurt my feelings, but I said, “OK, if he doesn't want to read it, then he doesn't. I've given him the opportunity. My mom is, in the carousel of parents, the one I've remained closest with, remained in constant communication with. It's been very, very difficult. But we have talked throughout the process of writing and when the galley arrived, I sent it to her. She read it twice in like three days and called me and said it was beautiful. Obviously the relief was palpable. I just really wanted to make her proud. I wanted the writing to hold up to the story, for her to be proud of the actual work of it.

Later, my father did read some of it and he got very, very angry, and then my mom decided she didn't so much love it.

It never occurred to me that I would be enough.

EA: Well that’s in keeping with the portrait you paint in the book. Your mom is your father's champion. She has built her life around him.

RC: That's right. And I did talk about that in therapy, and my therapist is like, "They live together! They have lived together every day for the past 58 years. Of course, that's how she's going to feel. What's she going to do?” But I've since had some very good conversations with my mom. And I think as is her way, she leads with love and I am leading with love to make sure that she knows that our relationship is more important to me than anything else. I know that the ship has sailed for them to understand or to interrogate or think deeply about race and the racism that I experienced, and that's that.

EA: Well, as a reader, I felt your love for them. Your affection for them as people, not just the love of a child, is really palpable in the book. It's there.

RC: Well what you hope is to approach it with as much radical compassion as you can, right? And, especially with my brother and sister, who were so different, I just wanted to make sure that I took care of them and their stories, so I hope that comes through too.

EA: We haven't talked about Tess, your birth mother, at all yet. I keep thinking about how you call your parents Mom and Dad, but Tess is always Tess. You talk about your carousel of parents, but in many ways, she's not a parent. She has this incredible hold over you, but you use very different language to describe your parents.

RC: The joke I used to have with my sister and brother was that our parents are really phenomenal people, but parents, not as much. But they did have our best interests at heart, and we knew that. My birth mother never had my best interests at heart; she just didn't. My parents and Tess, they’re polar in their approaches.

For me as an adoptee, what I wanted and needed was the mother who went down to the school and said, "You cannot speak to my daughter that way." And I didn't have that in my parents, which made me all that more susceptible to my birth mother's approach, which was veiled in being that kind of mother, but of course had little to do with me and everything to do with her.

My birth mother never had my best interests at heart; she just didn't.

And subsequently, I am that mother. Rest assured, I will go down to the school.

EA: That’s something I think about all the time. We're daughters and mothers simultaneously. We want so badly to be seen by our parents, and then we want to see our children in the way that we needed to be seen. And that, to me, was what was so beautiful about your book. It was you trying to make yourself seen.

RC: And having my son see himself in me, oh, that was so fulfilling — that’s not even the word. It was just this moment of feeling safe.

EA: Which is what was missing from your childhood.

RC: Yeah. Yes.

EA: That is very hopeful. I have always thought children have to feel safe so they can become safe adults, but as an adult, you can make your own safety.

RC: There's something about the lineage too that my son and I are making between us, which feels both ancient and brand new. It's something that I marvel at, and I am so thrilled that it's part of my everyday life. Because it never was before.

We haven't talked at all about your birth father. You don’t get to meet him until you're an adult, and he remains enigmatic. One of the saddest moments is where he talks about how he didn't have any family and how much it means to know you.

RC: That was a very painful thing to revisit because I knew, in the same way that I had not been ready to meet my birth mother when I was 11 years old, I was not ready to meet my birth father when I met him. I was ready to meet the father I wanted him to be, but I had not adequately gotten rid of the white gaze. I still used it as a lens. When I looked at him, I saw what Tess saw. And that is so deeply painful to admit. Later I thought, "There will be time. I want to try. I want to know him and figure out if we can make this dynamic work." And then he died, so we never had time.

But I have a picture of him that Tess gave me, when he was young. And about a year ago, I texted it to Kofi, and he didn't say anything. And I told my friend Caryn about it and she said, "You know he has that sitting right up on his phone. Right. Up. On. His. Phone."

When my birth father died, a friend of his sent me the program from a very small service they held. And it said, “He cherished the memory of a daughter.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. You can order a copy of Surviving the White Gaze here.