If You Can Make It Here

Why Don’t My Kids Have My Accent?

Born and raised in Brooklyn, my little New Yorkers sound like their Midwestern dad. I’m not thrilled.

I long ago accepted that my twin girls weren’t going to look like me. One is a copy of her dad and the other one looks like her paternal grandfather and his family. (Right now, I have a couple of college girlfriends reading this and thinking very supportively, “But she is the spitting image of you,” to which I rebut: You have not been to Minnesota for their family Christmas brunch to see the genetic evidence.) I was there for the begetting of them — the beginning, middle, and the white-knuckle end — but you wouldn’t know it to look at us.

I’ve always consoled myself that my girls might not have the nose of anyone I am related to, but they are born-and-bred New Yorkers like me. We’d have the truly important stuff in common.

Except as they got older, lost that cute kindergarten lisp, and started talking back to me, I realized my New York kids don’t have my New York accent. And it drives me bonkers.

I did a lot of hard work to get these kids here, and now they can’t even say Flah-rida like a normal person?

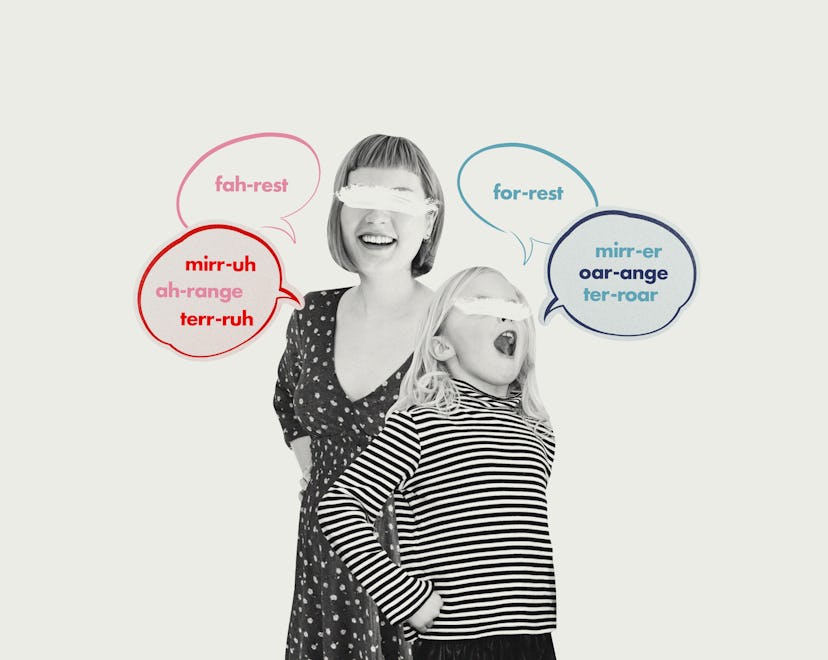

Mine isn’t a full “fuhgeddaboutit” New York accent, but I say “ah-range” and “fah-rest” instead of “oar-ange” and “for-rest,” “terr-ruh” instead of “ter-roar.” My accent is part of my identity, a thing that marks me as from here, and one that I never thought I would not pass on, since I talk the way my parents do and grandparents did. But being born, raised, and living with me in our apartment seems to have had zero effect on my kids’ accents. My fifth graders are fifth-generation New Yorkers, and they look in the “mirr-er” instead of the “mirr-uh” and pronounce Paris like it’s a mealy-mouthed fruit — “P(e)aris.”

In fact, they pronounce most words like their Midwestern father — who loves this, as you might imagine — and they make fun of the way I say carrot. I’d understand if we’d moved to California or Cleveland, but we’re right here in Brooklyn! I did a lot of hard work to get these kids here, and now they can’t even say Flah-rida like a normal person? Whither my children’s diphthongs and inglides?

Turns out that while language is acquired first from the parents — yes, it’s all that baby talk — as are accents, but at a fairly young age, kids leave the house for school and play with a new group that is way more influential: their peers. “This tends to happen in early childhood, around ages 4, 5, and 6, as children spend more time out of the home and less time with the family unit in their social and emotional worlds,” explains Kendall King, a professor of second language education at University of Minnesota. “We talk like the people we want to identify with.” This accommodation theory explains why children of immigrant parents don’t speak with their parents’ accents. “We adapt to other people’s accent or lexical choice when we want to mirror them,” she says.

In other words, children will take on the accent of wherever they live and go to school, if they move from their home country or to a new regional area. “Children are pragmatic,” says Amee P. Shah, Ph.D., speech pathologist and professor of health science at Stockton University. “They are very good at picking up the social communication patterns of their environment.”

So why do my kids have a different accent while staying in the same place? My affluent neighborhood in Brooklyn is home to many transplants from across the country and around the world. Many teachers at the public school they attend are not from New York. “New York has so much heterogeneity, kids aren’t as exposed to the dialects anymore, and they don’t get any value from sounding a certain way,” says Stockton University’s Shah. (Rude, but I get it.)

As it turns out, it’s not just my kids. All New Yorkers are changing the way they talk, gradually losing their wide range of vowel sounds (they produce about 14 or 15 of them, more than other American English speakers) and dropped R’s. “The features of the classic accent are in decline,” says Kara Becker, associate professor of linguistics at Reed College, who has studied New Yorkers’ accents. For example, the use of the post-vocalic R (New Yawk, instead of New York) and the inglide that stretches out vowels (cawfee, instead of coffee) is decreasing over time. Say this sentence aloud: I was merry when I saw Mary marry. If you pronounced each M-word differently, then congratulations, you might be an old-school New Yorker!

Linguists can’t point to one specific reason the accent is receding, but note that along the entire East Coast people are losing dropped R’s, and in general, the country is headed toward having a neutral accent. While in New York “cot” and “caught” still sound different, the “Mary merry marry” merger is starting here as well. Michael Newman, professor of linguistics at Queens College of the City University of New York, assures me that this has been going on for much longer than I think. “This is the tail end of a very long process where everyone used to say ‘Flah-rida’ and ‘ah-range’ and it got reduced to New York,” he explains.

Which leads me to my complicated feelings about my own accent. Proud as I am to be a New Yorker, the classic New York accent carries with it a good deal of stigma. The accent has zero prestige and has been associated — at least in movies and TV shows — with criminals, rudeness, and a general lack of class. While patrician New Yorkers of the past (exhibit: any FDR speech) dropped as many R’s as a gangster in a zoot suit saying “Toidy-toid Street,” many New Yorkers worked hard to not sound like they were from here at all.

Anne Elise Li grew up in various neighborhoods in south Brooklyn from Brooklyn Heights to Dyker Heights. While a student at the University of Chicago, she recalls her humanities professor saying “You seem like a smart girl, but you sound like an idiot.” She worked so hard to sound different that when she went home and ordered a “choc-o-late” ice cream on Montague Street, they didn’t know she was from the neighborhood. “I sound different now from my brother,” Li says. Her husband is a native of Shanghai, and Li says they will type a word into Google to find out how to pronounce it correctly for their kids, ages 13 and 9.

I mourn the severing of a phonetic link between my children, myself, and the generations before me.

But for me, it’s vexing that my children have a different accent from me while living in the same place. There’s some ego involved of course — I assumed my children would sound like me, not pronounce words Midwesternly! But I am also mourning the severing of a phonetic link between my children, myself, and the generations before me. It’s a trope that anyone over the age of 30 remembers a different New York, but it’s jarring to think that the way I speak could also be a relic of the past, the way distinct neighborhoods from Harlem to Williamsburg are radically changed by new condos and 80-story towers. The New York of my childhood, the one with Checker cabs and permanent Cats billboards and unbroken blocks of five-story buildings, is gone forever.

Perhaps it’s best to think of myself as a living legend, not the last of a dying breed. On the upside, while the dialect is changing, New Yorkers can still be identifiable as New Yorkers, according to the experts. “The sounds might get neutralized, but not the vocabulary. There are so many words and phrases that ID you as from the East Coast or New York,” explains Shah — think bodega and grab a slice. “And there’s the pace of speaking; it’s faster and the vowels are compressed.” Newman says the accent will be more regional than hyperlocal. “The new New Yorkers are sounding more like people in Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania.”

In other words, my kids have a New York accent — it just doesn’t sound like mine. It’s their very own.

Sunshine Flint is a Brooklyn based writer and editor, who has written for the Wall Street Journal, Afar, Scary Mommy, and more.