This Book Belongs To

Telling Kids The Story Behind Their Meals Is One Genius Way To Inspire A Picky Eater

Read this tale to your kid and then order Chinese food tonight!

There are many good tips on how to get a picky eater to try new foods. My favorites include having kids help garden (because they will want to eat what they grow) or have them help cook (because kids will want to eat what they cook). But neither of those tips are helpful when you are eating in a restaurant, especially one that doesn’t have a kid menu with mac and cheese or chicken fingers. This dilemma is particularly poignant to me because a good many of my family reunions, birthday celebrations, weddings, holidays and just Friday dinners take place within the red and gold rooms of Chinese restaurants. As a second generation Asian-American, my daughter would often look at the food with an abundance of caution.

Which, of course, I wished for her to free herself from. Food is one of the very few physical ways that we can experience history of the world. Delicious food is like a love letter from past generations, and it’s one we can pass on to our future, too. And, for me, Chinese food has been one of few roots I used to claim my heritage, one that I truly wanted for my daughter to have as well.

Consequently, over the years, I have found my own successful strategy to entice her to try Chinese food — and that has been through stories. I found that when I told her the story, the myth, or the legend behind the dish we were eating, she would inevitably give it a try. For who can resist when you tell about a competition between four dragons that inspired the chow mein on your plate or that a wall made of “these very same kind of rice cakes” saved a city from starving?

Even better, my daughter would often take the stories and tell her friends, who then would want to try the dish, too! This was especially heartwarming, because to her non-Asian friends, it made “foreign” food become a familiar favorite — which I believe can translate to relationships as well. And that would truly bode well for everyone.

A life without dumplings, Sizzling Rice soup, Peking duck or Mu Shu Pork would be a life so much less rich, so much less full, and so much less satisfying.

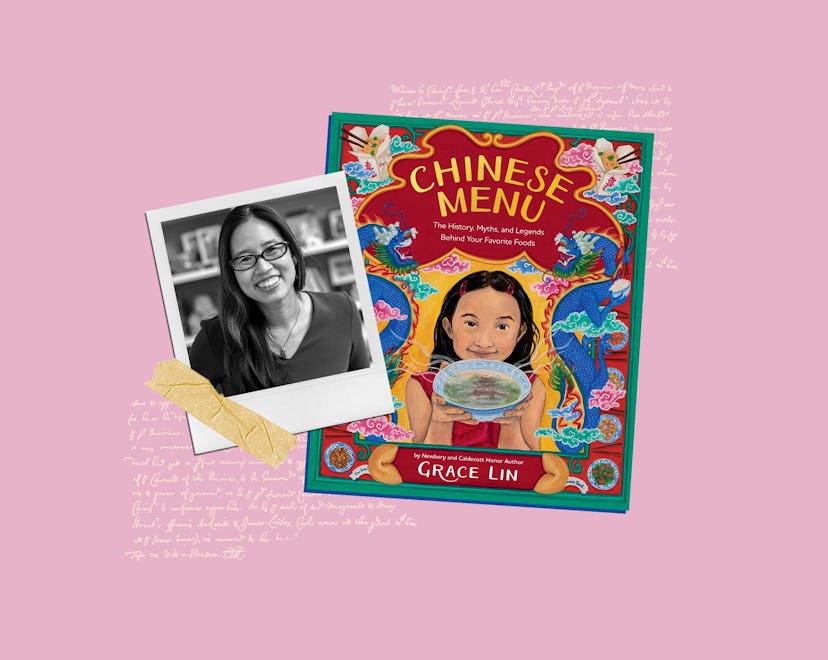

My book Chinese Menu: The History, Myths, and Legends Behind Your Favorite Foods has many of the stories I have told my daughter. And, looking back, I realize the book has many of the stories my own parents told me at dinner as well. Perhaps, without ever revealing it to me, they employed the story-telling trick to tempt me into eating, too. If so, I am glad. A life without dumplings, Sizzling Rice soup, Peking duck or Mu Shu Pork would be a life so much less rich, so much less full, and so much less satisfying.

So, if you’d like to give your kid (and yourself) the gift of a more flavorful life, consider my little trick of storytelling. The following is the lovely story behind Buddha’s Delight from my book Chinese Menu. Maybe order out for some Buddha’s Delight for dinner tonight and share this story, excerpted from my book, while you eat — I think it will make your meal more delicious!

Budda’s Delight

With all the imaginative names on a Chinese menu, sometimes vegetarians have a difficult time choosing which dishes they can eat. However, most know that Buddha’s Delight is a safe choice — as long as they don’t get it mixed up with Buddha’s Temptation or Buddha Jumps Over the Wall! Either of those (they are actually two different names for the same dish) will be full of meat — and maybe even shark fin — and all kinds of ingredients that vegetarians and Buddhists might want to stay away from; though crafty proprietors have always been happy to encourage Buddhists to break their vows — hence the name “Buddha’s Temptation”!

But a true Buddhist meal is vegetarian. One of the teachings in Buddhism is not eating meat because all life is sacred, including the lives of animals (Buddhists usually do eat eggs and milk, since the animal is not harmed). So, Buddha’s Delight (Luohan zhai 羅漢齋, literally Buddha’s Fast — “fast” in this case meaning “diet” or “intake of food”) — a medley of vegetables stir-fried until tender in a savory brown sauce with no meat — is the perfect dish for a vegetarian. However, it’s a delightful dish for nonvegetarians as well. I am not a vegetarian, but Buddha’s Delight is often included in my take-out order — because I love it! And I’m not the only one. Buddha’s Delight is popular all over the world, finding its way into American Chinese restaurants in the 1960s and now served daily. However, in China, Buddha’s Delight is often eaten on the first day of Lunar New Year — one of the most important celebrations in many Asian countries.

The Chinese tradition of Lunar New Year has a multitude of customs and superstitions (such as don’t wash your hair for the day or else you might wash away your luck!). So, some eat Buddha’s Delight for good luck — because eating a dish that has not harmed a living being is a virtuous way to start the year, and such virtue will hopefully be rewarded! Others eat Buddha’s Delight as a way to return to healthier eating — after the rich, decadent feasting of Lunar New Year’s Eve, a dish of all vegetables is pretty good for your digestion. And of course, a lot of people eat Buddha’s Delight on Lunar New Year for both reasons!

There are many variations of Buddha’s Delight. At Lunar New Year, people make sure they include symbolic vegetables like bamboo shoots (representing new beginnings) or noodles (for long life). And nowadays, to make things easier, most people just have nine or ten ingredients. But the traditional recipe for Buddha’s Delight calls very specifically for eighteen ingredients. Why? Well, it’s all explained by how Buddha’s Delight was created.

During the Song Dynasty, around 1120 CE, there was a Buddhist monastery in the city of Guangzhou. The Buddhist monks at this monastery were very devout and followed a strict schedule of meditation, prayer, work, and begging for alms.

Now, begging for alms — asking for donations of food — is an important part of being a Buddhist monk. Not only do the monks need food to survive but the monks believe their begging gives people a chance to do good deeds. And by doing good deeds, the monks believe that the givers will earn merit and will be blessed. To Buddhist monks, begging for alms is thought of as a circle of kindness.

So, one day, as according to their practice, the monks of the monastery dispersed to beg for alms. Six of the monks went east, toward the city. Another six monks went west, toward the village. The last six went south, toward the farmlands. But eventually all eighteen of them separated and walked alone, each carrying their begging bowls quietly.

The monks returned just as the sun began to arch overhead. While none of the bowls were empty, none of the bowls were full, either.

“In the city,” one of the monks who went east said, “we were given bamboo, bean threads, pressed tofu, fried wheat dumplings, dried black mushrooms, and pickled radish. But only a little of each.”

“In the village,” one of the monks who went west said, “we were given wood ear mushrooms, lotus root, golden needles, gingko nuts, bamboo shoots, and water chestnuts. But also, only a little of each.”

“The farmers gave us many things…,” said one of the monks who had gone south, “bean sprouts, celery, broccoli, peas, corn, and some cabbage. But, like all of you, a small amount of each.”

“Venerable friends,” another monk said, “it is obvious that none of us were given enough to make a meal for ourselves alone. However, if we combine what we were given, we may be able to make a dish that we can all share.”

The other monks quickly nodded in agreement. Together, they worked to slice and peel the vegetables, soak the dried food, and start the cooking fire. When all was ready, each put their collected food — all eighteen ingredients — into a heated pan with a little oil. As their food was cooking, one of the monks found some soy sauce and sesame oil to add as well.

And then it was done. As one of the monks let the mixture slide onto a large plate, all the monks breathed in the enticing, warm aroma — their eyes widening in surprised pleasure. In a matter of moments, the monks were devouring their portion like hungry oxen. When they finally finished, each looked up from their bowls at one another.

“That was delicious!” a monk exclaimed. “What good fortune that none of us were given enough to eat — it caused us to share our food and create this dish!”

The other monks smiled and laughed in agreement.

“Yes,” another monk said. “From now on, we shall always do this. We will put our donations together to make and share this delight!”

So they did. The dish became a daily meal at the monastery and soon other monasteries began to do the same. And not long after, the recipe found its way out into the villages, cities, and farms and all began to make and share this divine Buddha’s Delight.

Grace Lin is the award-winning and bestselling author and illustrator of Starry River of the Sky, Where the Mountain Meets the Moon, The Year of the Dog, The Year of the Rat, Dumpling Days, and Ling & Ting, as well as picture books such as The Ugly Vegetables and Dim Sum for Everyone! Grace is a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design and lives in Massachusetts. She invites you to visit her online at gracelin.com.