Books

Kate Baer & The Peculiar Experience Of Being A Mother Online

In I hope this finds you well, Baer creates poetry out of the ugliness and loneliness of the internet.

A reluctant adopter of most technological advances, I most likely joined Instagram back in 2013 because I, too, wanted a chance to imbue my sh*tty iPhone pictures with 1970s nostalgia by way of the Rise filter. It’s impossible to remember how much I was thinking of my self-presentation on the Internet way back then, but I think about it a lot now. I mostly restrict myself to innocuous photos of toddler curls, Funny Things my kids say, and quips about being tired. Motherhood is hard enough without being accused of being a selfish b*tch who never should’ve had kids in the first place if she thinks it’s such a drag.

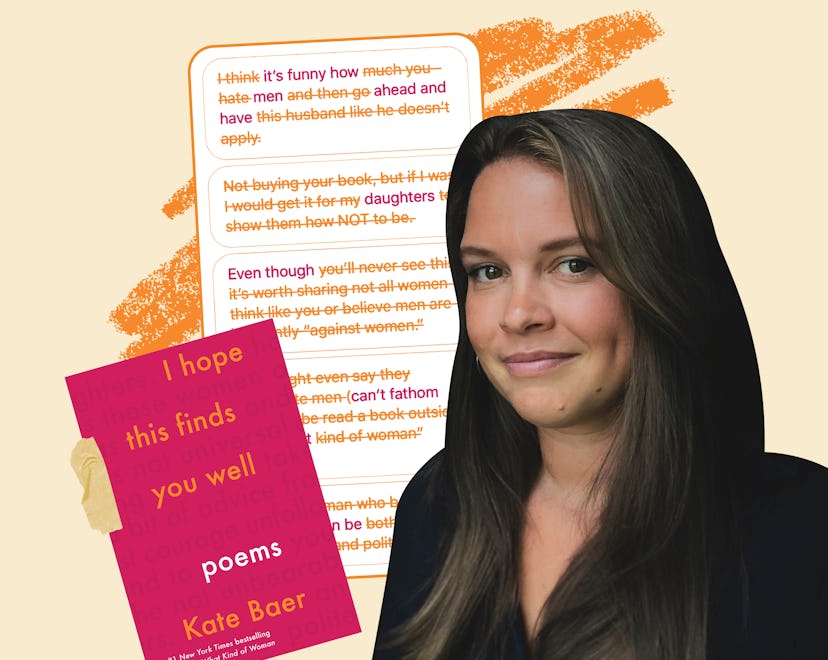

We’re all open to public scrutiny when we share ourselves online, but being a woman or mother online is a very specific type of occupational hazard. Kate Baer explores this particular experience in her new poetry book, I hope this finds you well, out now. The book features Baer’s now famous “erasure poems:” searing responses to the condescending, infuriating, misogynistic messages she receives from assorted well-wishers. Using obnoxious emails from the internet’s Chads (and sometimes Karens) as her starting points, Baer erases words from the original messages to create poems that make most of her fans respond with all caps, fire emojis, expletives, or a combination of all three. I am one of those fans.

Most of the time I chalk it up to ‘Chad’ rhyming with ‘Sad’ and a gross failure of imagination. But of course, it’s also something deeper — isn’t it?

Many of Baer’s erasure poems are in response to messages outlining her “bad” motherhood, which as far as I can tell, is illustrated by her happening to be a mother and happening to be online? Baer confirmed to me in an email that her “bad mom” accusations are predictably arbitrary and nonsensical. “Either I should be working less or showing my body less or never (EVER) complaining about being a mom,” she says. “It’s so boring I can hardly repeat it. Most of the time I chalk it up to ‘Chad’ rhyming with ‘Sad’ and a gross failure of imagination. But of course, it’s also something deeper — isn’t it?”

In I hope this finds you well, one Chad warns that Baer’s children “will be unearthing all sorts of trauma in therapy or elsewhere” because Baer continues to commit the crime of being a woman and a mother who insists on making herself visible. Her poem in response reads: “I could ask / you / to / love / me / instead / I hope you / meet the / earth / where / she / bruises / and know / your / place / in the / history / of / things.”

Insert fire emojis here.

Baer has 142K followers on Instagram. Vitriol from strangers might not be a daily concern for women and mothers with smaller platforms, but I talked to several moms for this piece, and while their experiences varied, all of them expressed an awareness of self-policing when it comes to Being Online.

One woman told me via DM that her online presence led to her ex-husband crafting a narrative about her supposed unfitness and “immorality” as a mother in a custody battle. “He even bragged about how he'd stalked me online and said that I was ‘highly Googleable.’” Another woman I spoke with, L’Oreal, has roughly 16K followers across all of her platforms. She tells me she was “definitely hesitant” to talk about her perinatal depression on social media simply because so many of us have been conditioned to “perform” pregnancy as a solely joyful event — she was afraid of “letting people down.”

Of course, all of this self-scrutiny and anxiety is compounded by varying levels of marginalization. Baer notes as much in her preface: “As a cisgendered white woman — I am merely the tip of the iceberg that launches straight down into a deep and ugly sea.”

Tomi Akitunde, founder of the “Black Mom Google” blog, mater mea, tells me via email that while white moms can occupy various “mom identities” online, there’s a “very limited view” of what Black motherhood looks like on social media. “There's this visual expectation of what Black excellence and success looks like,” she says. “We aren't really afforded the opportunity to be a mess and to not present as pulled together. There's a cost, both social and real, like, in thinking about who's allowed to be a wine mom, who's allowed to joke about using substances to handle having children and who gets penalized for that.”

Who wants that kind of attention?

Disabled mothers might be wary of being too transparent online knowing that in several states, their disabilities can be legally leveraged against them in custody battles. Writer Rebekah Taussig emailed to explain her specific self-censoring lens: "Everything I share online is filtered through the deeply embedded skepticism our culture carries toward disabled parents. The laws and their implications change the stakes; I am scrutinized in a way nondisabled mothers aren't, and that makes it terrifying to share the rougher edges of my parenting experience."

Queer mothers fight against heteronormative ideals. Dana tells me she has to be “to be very careful how and how often I present myself online as a transgender mother. For many, motherhood is the essence of womanhood... and some will argue against the right for my wife and I to be parents altogether. Who wants that kind of attention?”

The fact that so many of us, regardless of our specific life experiences or identities, feel pressure to perform the right kind of motherhood and womanhood on social media illuminates the validating power of Baer’s book, which more than anything else, is an exploration of how this pressure to be permeates our individual experiences of motherhood and our collective maternal consciousness. When I ask Baer how her experience of performing herself online has changed since writing the book, she says, “I don’t feel like writing this book has taught me anything about the Internet other than confirming that it’s often a very lonely place full of very lonely people. I don’t know how my identity online has been affected by that. I am more guarded than I was in 2003, but I think we all are.”

Ultimately, of course, being a mom and woman online is just like everything else that happens online: often bad and stressful (and often worse and more stressful for some), and occasionally beautiful. Many mothers (particularly those from marginalized communities) can find communion with kindred spirits online more readily than IRL. In her book, Baer speaks to this potential in poems which respond to the many positive, heartening messages she’s received. In “Re: Comment Section Under Fat Girl Smiling in a Bathing Suit,” for example, Baer responds to three strangers thanking her for simply posting a photo of herself in a bathing suit online. “As a girl who / wished / to exist / I never thought of / my body But / After birth / I am strong / I get back up after / crashing I / take up space. My body / and yours.”

Poems like this illustrate the fact that while crafting an online image as a woman or mother is not for the faint of heart, sometimes we can find genuine bursts of connection, simply by having the courage to put at least one side of ourselves out there for others to see. As Baer writes in her book, “My hope is that by sharing these pieces, we continue to hold on to the truths that sustain us, and when we do encounter the inevitable noise — we tune our ears to hear the song.” Chads be damned.