How to Talk So No One Will Listen

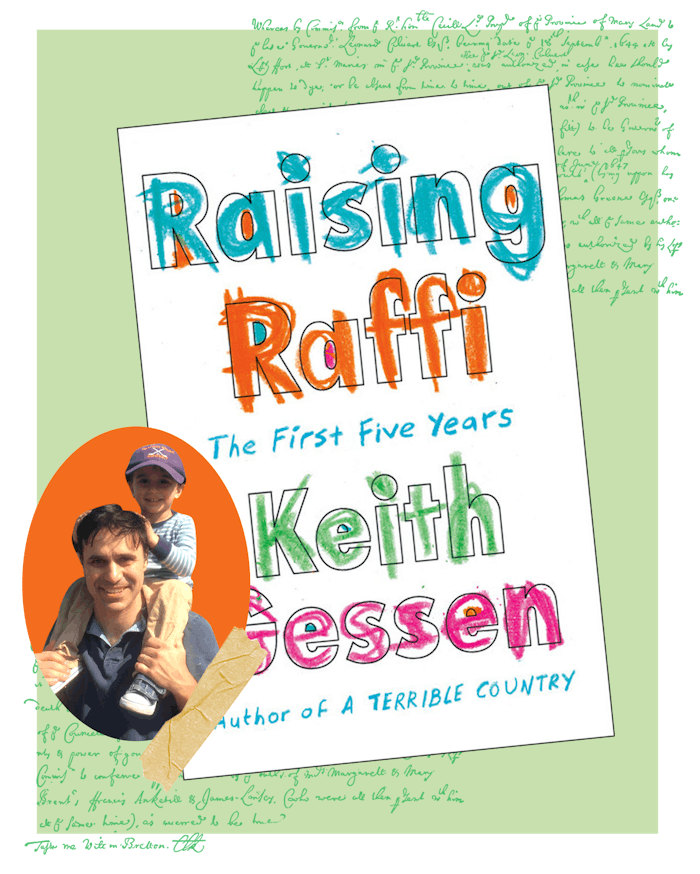

Keith Gessen’s Raising Raffi Is An Instant Classic

The parenting genre’s unavoidable conceit is that a generalized piece of advice will work on one’s specific children. The central subject of Raising Raffi is a particular child on whom it does not.

A mother of two sons once told my pregnant wife and I that if our first child was a boy, he should be our only child, since we could not risk having another. Anyway, Keith Gessen and the writer Emily Gould also have two boys. Gessen’s book Raising Raffi is about their oldest. It is something of an instant classic, though perhaps I am not one to say. Most parenting books I put down drowsy-but-awake. I had forgotten all about the French pediatricians, Bébé’s “le pause,” and the Tiger Mom before Gessen reminded me. The parents of handfuls face a reigning behaviorism: multiple choices and outright bribes; stars, snacks, and scripts of de-escalating feints. It is a constant struggle with all the time in the world to lose. One recalls that line of Lauren Groff’s: “I have somehow become a woman who yells.” (And I have somehow become a man with a Google doc where he notes to himself things like, “Minimize your reactions so that negative attention doesn’t become its own reward — Do less.”)

The eponymous Raffi is clearly recognizable to me as a charmer, parented immaculately, even though, and no doubt in part because, his father describes many a parenting choice as “a small defeat.” Parenting does come with readily available instruction manuals. It’s just that some of the instructions could hardly be more abstract and difficult to follow than if they were designed to fail. “The damage — to your child, yourself, sometimes to your marriage — has already been done,” Gessen writes. “That is the way of knowledge, though. In its purest form, it always comes too late.”

Like so many of us, Raffi’s parents put him through the paces chalked out by the literature — timely, impure, and seeming to capitalize on our anxieties. Even at its most practical, parenting advice is paradoxical. While we are told early on that all babies are different, we find out on our own that differing parenting methods stand in withering judgment of their opposites. See: “sleep training” or “natural birth.”

The parenting genre’s unavoidable conceit is that a generalized piece of advice works on specific children; the central subject of Raising Raffi is a particular child on whom it does not. Gessen finds himself at the end of his rope and acting like the kind of father he never wanted to be. In search of a nonpunitive model, Gessen introduces us to Jonathan Tudge, a professor of developmental psychology whose technical argument is more or less that a child develops independent of a parent’s attempts to improve them, and that both parties are products of their culture. (I can only assume this is indie rock 1994–2008 Tudge is referring to. Parents who “want a range life,” if you will.) Kenyans and Finns — and even Americans and South Koreans blowing past the WHO’s ill-timed advisory on screen time — parent in different ways and in different contexts without meaningful differences in outcomes. I felt relief at being halfway convinced of this; I had tried to adopt my own school of thought even as I gravitated toward pictures from the late ‘70s of my friends’ moms smoking cigarettes while pregnant, so fervent in my hope that the errors of our ways were not so fateful as the loudest voices in the school board meeting would have it. As the Gould-Gessen household struggles with remote learning, Gessen seeks out his own beloved second grade teacher. Her advice shines so goldenly I will leave it to the reader to find out what it is and that it doesn’t work either.

The generation that hovered off-screen during Zoom-school is already making the parenting writers it needs, those who value testimony over prescription.

Guidebooks aside, parenting writing is actually better than it ever has been. The message boards and comment sections harrying writers who admit to anything less than procreative bliss are still with us, but in newsletters and revamped magazine coverage, women predominantly have shouldered the burden of advancing the form: Jen Gann, Amil Niazi, Angela Garbes, Gould herself. Lydia Kiesling’s parenting realism in fiction. Lyz Lenz leading the fight against cooking. (Which, to be clear, I do every day and will never do again.) Gessen quickly dismisses the notion that there is such a thing as “dad literature.” I remember when I first became a parent and the search returns for “stay-at-home dad,” which seemed to imply that it was not a serious thing to be. It was more like a premise for a hilarious sitcom: My One Dad (married, filing jointly). Of course, this hypothetical subgenre is undone in its assumption that fathers should feel no stake in parenting writing as it is. But there is something fatherly in how Gessen describes his unpreparedness — a game amateurism deeply familiar to me, at least. My parenting microgeneration would be best expressed by a song on the radio about waiting until you’re in your mid-30s in a coastal city and you’ve tried all the restaurants. This is wiser in some ways, riskier in others — one carries with them into child-rearing their fully developed self-involvement. As we were expecting, I promised myself to sacrifice whatever it took, but at the same time I could not relinquish a natural inclination, as a Brooklyn resident with a Wi-Fi signal and a nearby farmers market who had watched The Sopranos all the way through four times but only once in the past five years, to do whatever I wanted with every minute of my day. This inclination cut against the grain of parenthood, which took most every one of those minutes and broke them into small, chokeable pieces.

The new-school parenting writing speaks to a common stress — of being necessarily new to parenting and yet failing to be a new kind of parent. (See Jessica Winter’s gently skeptical overview of “gentle parenting.” Negative reinforcement may not work on kids, but it for sure works on parents reading the phrase “brain architecture.”)

For parents of school-aged children, the pandemic has been a psychological experiment, a policy crisis, and an absolute vise laying bare our society’s foundational assumptions that child care comes included in a gender role, and that real work is attending a remote meeting in a closet with the household’s most presentable books in the background. What kind of role does parenting advice play now, knowing what we know? The generation that hovered off-screen during Zoom-school is already making the parenting writers it needs, those who value testimony over prescription, and who can speak equally well to focused political action and walking outside to scream.

In a very real sense, parents reach out to books like this one with a last frayed nerve. Every act of honesty is an act of generosity, and this book is deeply generous.

While reading about Raffi taking off down the street, I had the poor taste to reminisce on the privilege of raising a child in New York City. In brownstone Brooklyn, a beautiful heretofore unimaginable baby was utterly insignificant. Parenting was generic but still rather pricey. We had the same things everyone had: an Uppababy Cruz (and not the two-seat-adaptable Vista one buys after making a plan with God); patterned swaddles from Big Muslin; recalled rockers off the street; a very popular chicken costume for Halloween, from Target. At the same time, there was a recognition, when I had the newborn on the leafy, trashy street, from anyone who’d had a child, I think, of how special my life was. One day I heard a mother murmur, “Look at the baby,” to her kid and did not need to turn and look to know that it was the voice of songwriter Sharon Van Etten. Current NYC residents often struggle to justify what is readily known to those who have left. The point of life is to live in that city. Parenthood is the same kind of nonsense. The point is to provide and then surrender; to encourage resilience and never get over it. Is that tragic?

Parenthood is a drama of what can and will go wrong. Given any intermission at all, I will memorialize the other lives I might have lived, lives replete with convenience and abundance and where I utilize my normal speaking voice at all times, lives marked by small narcissistic differences I now cherish, regardless that these lives have collapsed into the one I infinitely prefer, the one with my children.

In a very real sense, parents reach out to books like this one with a last frayed nerve. Every act of honesty is an act of generosity, and this book is deeply generous.