Life

There’s Still A Lot You Don’t Know About Naomi Davis

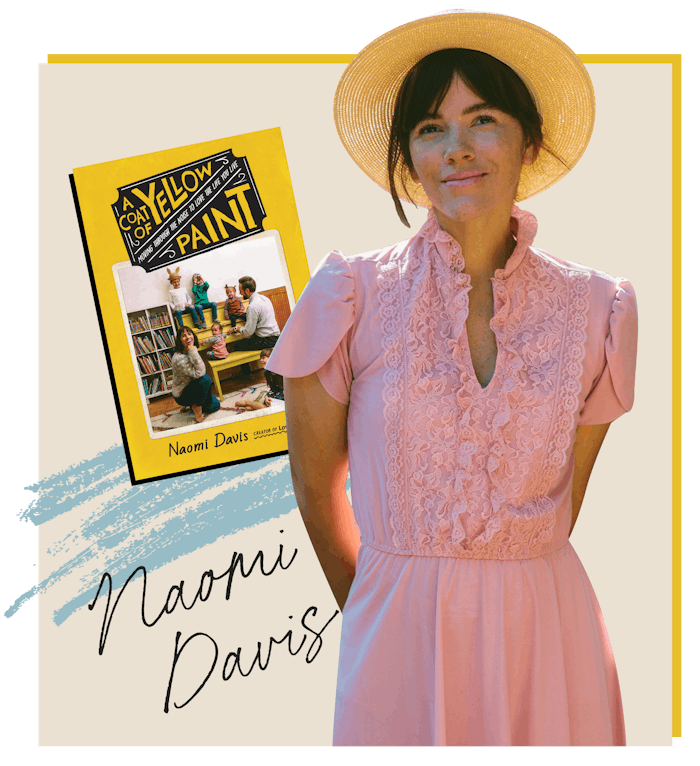

The longtime blogger-turned-influencer known as Taza is ready to share more of her life now, and it’s all in her new book, A Coat Of Yellow Paint.

Naomi Davis has her hair in pigtail braids with her trademark bangs, and is wearing a dark denim jumpsuit. She’s not wearing makeup, as far as I can tell, which is in keeping with her vibe lately, or what she shares of it on Instagram.

When I tell her I have never been so starstruck in my life, she waves me off but I mean it. Like many people I know, I have been reading her blog for over a decade, way back when she was “rockstar diaries,” back before she had kids (she now has five of them, ages 9, 8, 5, and 2-year-old twins). I’ve watched her babies grow from pregnancy announcements to prepubescent humans — people unto themselves — and I feel genuine nostalgia whenever one of their birthdays comes along and Davis shares their baby photos. I've been engaged in a one-sided intimacy, consuming her face and her innermost feelings, plus every trip to get ice cream or change in hairstyle, for so long that I feel like we are old friends, despite the fact that, until this morning, she had no idea who I was.

When I tell her all this she visibly brightens and relaxes, tells me "this is less scary now,” and asks me about my own children and we chat for a while about sleep and potty training, like two moms at the playground who just met.

To a certain elder millennial, Davis — aka Taza — needs no introduction, but when I ask her how I should identify her, what I should say she "does," she stumbles. “It's so funny, I struggle so much with titling myself. I get so antsy if someone asks me in an elevator, ‘What do you do?’ I always answer, ‘I'm a mom, I have five kids.’ It's how I still envision myself to this day."

“I don't know if I can graduate to a title of writer, yet. I know that I have a book coming out but I'm still like, ‘Oh, maybe someday I'll be able to say I'm a writer.’”

Davis, who will turn 35 this year, started her blog in 2007, the same year she married her husband Josh when she was still an undergrad studying dance at Juilliard in New York City. They stayed in New York for the next 13 years, proudly raising their five kids in Manhattan apartments. Naomi grew up in Utah, the eldest of five herself, and has been a lifelong member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Which is all to say that yes, Davis was part of the early-aughts wave of "Mormon mommy bloggers" whose archives lonely, heathen women like myself would read in their entirety, late at night, when we needed permission to think about things like marriage and babies, to imagine a completely different life.

You could call Davis an influencer, a mommy blogger, or a content creator ("All that stuff gets such a bad rap," she's quick to say, "but I've loved my journey through all of it”), but as of this week, she's now a published author, too. "I don't know if I can graduate to a title of writer, yet," she says, then laughs with a tinge of self-deprecation. "I know that I have a book coming out but I'm still like, ‘Oh, maybe someday I'll be able to say I'm a writer.’"

Her book, A Coat Of Yellow Paint: Moving Through The Noise To Love The Life You Live, is chatty and searching. The voice of the book is the same Taza her followers feel they know. She's got her same heart-on-her-sleeve sincerity, forthright but playful, but it's some of the subject matter that's different. She shares for the first time her struggles with infertility, her unhealthy relationship with her body, and a period of deeply questioning her faith, which is, as she puts it, a cornerstone of her identity.

Writing a book is new territory for Davis, something she had not wanted to do until recently, despite being approached by agents and publishers a few times over the years." Perhaps I wasn't sure if I could find the right words for the heavy feelings weighing on me, or perhaps I worried I wouldn't be able to write well enough and thus be misunderstood,” she writes in the introduction to Yellow Paint. “Perhaps I was scared of confronting the thoughts and feelings I'd pushed back and shoved down deep inside."

Over Zoom, the mood is lighter, and Davis exudes the confidence she once lacked. “If you had asked me seven years ago or five years ago, ‘Oh, would you ever want to talk about this?’" she says, her pigtails bobbing, "I'd be like, ‘No.’ I have boundaries in play. Everything I felt comfortable sharing, I was sharing online. And then it shifted.”

She says that there was this vivid moment, an afternoon in January 2019 when she "felt like she was 57 weeks" pregnant with her twin girls, that she sat down and started writing, tuning the chaos of her family out. She gets a faraway look on her face as she tells it: "Before I knew it, several hours had passed and I was still writing. After bedtime, I put everyone to sleep. I went back to my laptop and I couldn't stop writing. And after, as I printed everything, I was kind of in shock myself. These were such intimate stories, but I just felt this push. I just wanted to share it. And I realized that this was the start of my book."

She tells me it was important to her, given how personal the subject matter was, that she didn't hire a coauthor or a ghostwriter, but that the writing process was nothing like she imagined it. She had five children to take care of, including twin newborns, and a business to manage, all within the confines of a New York City apartment. “I didn't know how I was going to be able to do it, honestly. But it kept me up at night, and because there's never a good time, I knew I had to do it."

Publishing a book, especially one you’ve actually written, might seem like a sentimental career choice, especially when you have a more direct, and presumably more lucrative, access to an audience. Influencer marketing is an estimated $10 billion industry, and growing quickly, and Davis has been doing brand partnerships with big companies like Target and Capital One for years.

I think of her as a pioneer in the "space," and tell her as much. “I think I was just lucky with my timing," she insists. And to a degree I agree with her, but am quick to point out that without her charm, her aesthetic eye, her disarming sincerity, and her talent for photography, we would not be having this conversation. I think in another life, Davis could be a professional photographer. But then again, isn't she already?

Daniel Tiger helped raise my daughters this year.

We reminisce about the earliest days of native advertising on social media and lifestyle blogs. We were so much younger then, back when, say, a sponsored post featuring her children eating Diamond-brand almonds seemed scandalous and new. I'm not saying that Naomi Davis invented native advertising but she is definitely where I first heard of it.

She tells me the story of when she first sat down to talk about a “partnership” with the founder of Sweetgreen, Nathaniel Ru. At the time, more people knew about LoveTaza.com than the beloved salad empire, and Davis made her money from banner ads and links in the sidebar, not sponsored posts. "He was like, ‘Have you done this before?’ I'm like, ‘No, have you done this before?’ He's like, ‘No.’ He's like, ‘OK, well, what do you think makes sense?’ I went home and I'm like, ‘What should I do? What would make sense?’"

We laughed at this, and I marveled over the fact that 10 years later, she had a luggage deal with Target, and no one blinks an eye at an #ad, and most of the stuff I impulse-buy online these days is via the Shopping feature on Instagram (which, like true millennials, we agree is "scary" and "dangerous" — scarily frictionless; dangerously effective).

Many have speculated over how much money people like Davis can make from sponsored content, and she demurs on specifics but it was enough for her husband, Josh, to quit his finance job several years ago to work on the Love Taza empire full time.

But that was before the pandemic hit. In March 2020, Davis faced significant blowback after sharing that her family would be leaving New York City in a rented RV. Davis, as I see her, is a bellwether, and though many other New Yorkers would eventually follow suit and "flee" the city, this moment proved that her timing can be as bad as it is good: The day after they left, the CDC issued a travel advisory for New Yorkers, and suddenly the comments section of her Instagram post became a place for despairing Americans to project their anxiety and outrage. Buzzfeed News, among other outlets, had public health experts condemning their plan on the record.

The Davis family sojourn out West was supposed to be for just a few weeks, but Josh took a job in Arizona and they ended up buying a house and landing there permanently. "If you had asked me in February, ‘Would you ever live in Arizona?’ I'd be like, ‘O-M-G, no. I'm not into that. I'm a city girl.’" But her kids are thriving, and like many of us, she's readjusting her expectations for what her life looks like.

In classic Taza style, Davis is quick to mention silver linings, “gifts in disguise,” stepping back, and gaining perspective, and I remember that when she "went dark" and didn't post much on Instagram for a few months, I felt relieved. There are people you want to hear from during hard times, and people you don't. Many people in 2020 (though not enough) learned when to stop talking and listen to others, to take a step back and really think about what they were putting into the universe.

Davis’s particular brand of looking on the bright side and celebrating the little things can feel uplifting to some people, a bright spot on the internet, but to others, it can be straight-up annoying. In darker societal moments, the selling optimism of the influencer reads as delusional, if not spiritual bypassing. (Some of my friends who are also fellow longtime Taza-heads still talk in regretful tones about an ill-timed, cheerful post she made in November 2016 about her kid's adorable fundraiser to Save The Bats — a worthy cause, I’m sure, but a large portion of the country was reeling from Donald Trump’s election and, well, it just didn’t land.)

When she came back online, I remember stepping outside to stare at my phone like a businessman taking an important phone call. We Taza-heads were happy to see her, and shocked by the distinctly un-Taza aesthetic of their yet-to-be-renovated suburban Arizona home. Gone were her fake eyelashes. Her hair seemed air-dried? She was in comfy pandemic-wear and letting her toddlers eat popsicles at 8 a.m. Somehow it felt just right. "Taza has staying power," I texted, and felt relief. Davis' face was in my stories again. A sense of normalcy was restored.

That ability to know, to draw and maintain the boundary between her life and her social media presence, is what has allowed her to keep going for so long. Her online life serves her real life, and not the other way around.

When I ask her over Zoom how she managed to write a book in a new home, mid-renovation, with no access to child care, five young children, in a society that was actively shifting, she laughs ruefully, with that semi-crazed tone that parents who have been muddling through the past year all recognize. She talks about giving up on remote school, hiding in her closet for 30 minutes to work, or setting up an office in her car late at night. “We got our first TV. We got a gallery wall and I put up the Samsung Frame TV. Daniel Tiger helped raise my daughters this year. We have every song memorized.”

She says somehow it worked, and she met all her deadlines, but she's not sure she ever wants to do it again.

For the past decade, the most common criticism lobbed at Davis was that her life was too perfect, that her online presence painted a too-rosy picture of motherhood. But all along she had been going through the kind of real sh*t that, if she had shared it online, might have earned her more sympathy. Infertility, IVF, anxiety, and body issues — these are all common, and relatable, struggles. And anyone who's been on the internet long enough knows that struggle plays well. Her book reminded me, and it shouldn't have had to, that Naomi Davis is a human being and that it's actually sort of sick to demand people share their problems with an audience in real time before they've made sense of them themselves.

"Years ago," she tells me, "I swore to myself I would never talk about infertility and IVF. When I did try to go there sometimes, it just felt like I'd have to then open up all of the side notes, and try so hard to get someone to see where I'm coming from, or to have lots of disclaimers. I also just knew that I didn't necessarily have the proper tools or confidence to handle everybody else weighing in. And sometimes that's why I've kind of held things close to my heart, many of these things are almost sacred to me."

Or as she put it in the book, "At the time I knew that writing about these things would have broken me."

That ability to know, to draw and maintain the boundary between her life and her social media presence, is what, I think, has allowed her to keep going for so long. I get the sense from reading her and talking to her that her online life serves her real life, and not the other way around.

She's also in a better place now. Her Arizona house is still mid-renovation, but her living room is already the perfect shade of green. The shelves around it filled with squiggly neon candles, which I immediately clicked through to buy on Instagram, and her bright yellow book cover looks perfect perched next to them. "I'm really just hopeful that it can resonate with somebody else, and someone else won't feel as lonely as I felt in those moments of life."

And maybe because I've become soft, or because we are Zoom friends now, or because of this tentative, bruised, hopeful moment we are just on the edge of — but I believe her, and I nod vigorously, and feel proud.

This article was originally published on