Life

Two Moms Harnessed The ‘Productive Rage’ Of Roe To Open An All-Trimester Abortion Clinic

The Partners In Abortion Care clinic, one of a tiny handful of all-trimester centers, is a safe haven for care up to 34 weeks of a pregnancy.

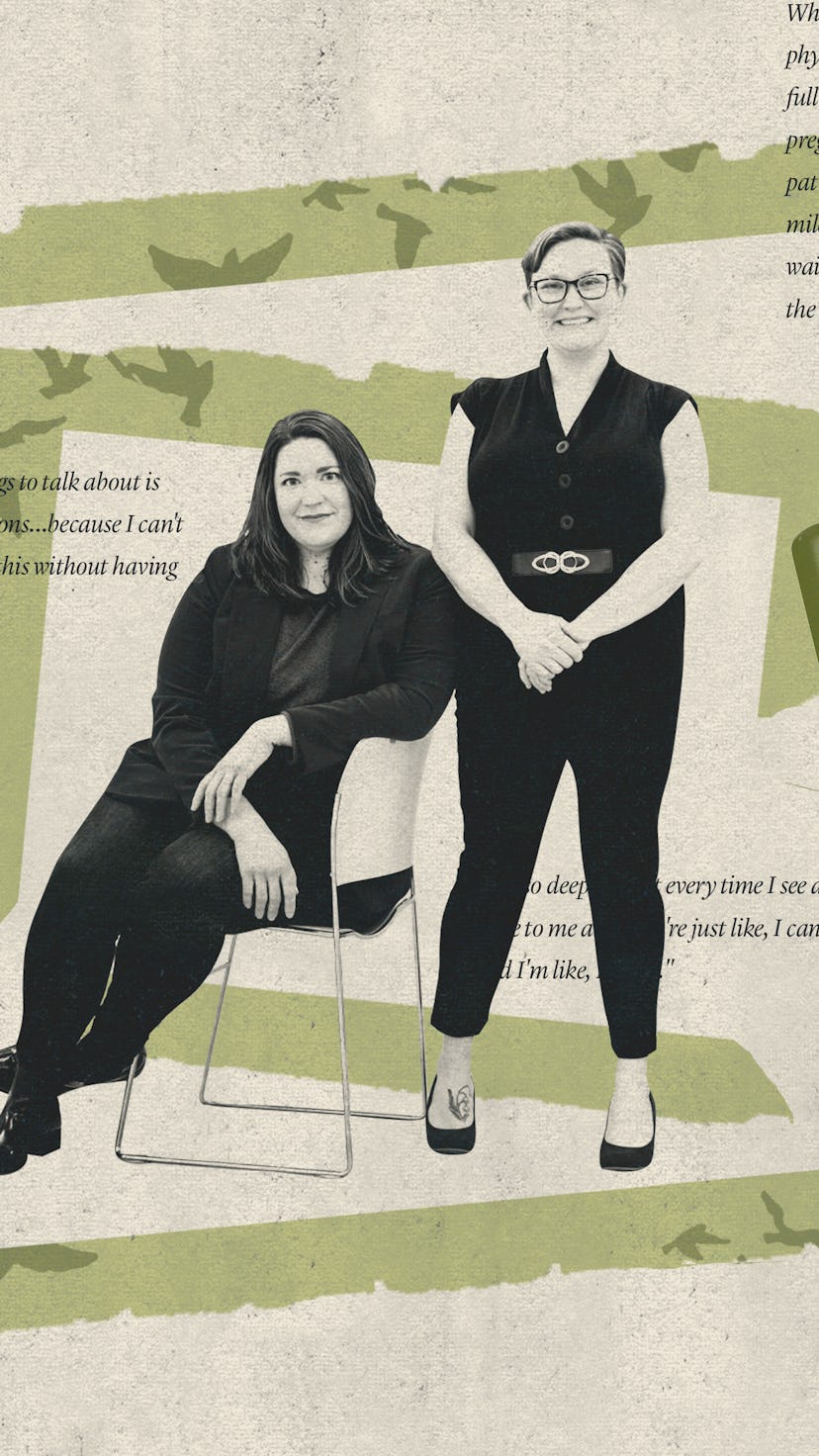

“We’ve trademarked the phrase productive rage,” jokes Morgan Nuzzo, a certified nurse midwife and a larger-than-life presence in her honey-blond pixie cut and glasses. She is channeling that rage into every piece of her work these days, as a co-founder — alongside her longtime friend and business partner, Dr. Diane Horvath — of a brand new all-trimester abortion clinic in Maryland. Called Partners in Abortion Care, it is a project that Horvath and Nuzzo have been dreaming about and working toward for years. Finally, having sourced medical equipment from a now-shuttered clinic in Georgia, pushed through the bureaucratic molasses of our health care system, and raised more than $400,000 through their wildly successful (and still live) GoFundMe, all while fielding threats and harassment, the clinic’s team has opened its doors, and its phone lines, to patients.

Partners is a destination for safe and legal care in the post-Roe era, thanks in large part to an international community of providers, clinic workers, activists, organizers — many of whom are also mothers, like Horvath and Nuzzo are. The collective effort of funding a new abortion clinic, of helping two fellow parents and care providers build something real and tangible and (literally) concrete was a bright light in the darkness of our summer, a spark of joy. That productive rage Nuzzo speaks of? Fuel for our multifaceted resistance to the intensifying criminalization of our work, the deepening and expanding violence that is state control over our bodies and lives.

Because of its location in College Park, Maryland, an access point for patients now forced to travel from the Southeast, Horvath and Nuzzo’s clinic will be the last hope for millions of Americans now living under state-imposed restrictions and bans, many of whom are pregnant children and teenagers. It is also a last resort for people for whom pregnancies are health risks or death sentences, who have survived rape or incest, who are carrying nonviable pregnancies or in need of the miscarriage management that local providers often refuse, and anyone who is simply pregnant when they can’t or don’t want to be. In the brick office complex outside of Washington, D.C., the two women are now ready to provide the full spectrum of trauma-informed and affirming abortion care to any one who needs it — no matter what.

“I am not a religious person … but this is a blessing; this is sacred work; this is a calling.”

On the sunny June morning I interviewed Nuzzo and Horvath, my own phone had been buzzing for hours. In my nonparenting and nonwriting time, I work as a community abortion doula and a medical assistant at my local reproductive health care clinic, and the pace of our work was suddenly ramping up as state-level abortion bans proliferated. Folks in need of care have been forced to travel to “safe” states like mine for their appointments, and there has been an influx of desperate requests and patchwork solutions. These days, many of the calls, texts, and emails I’m fielding are from people I can’t help. Some can’t afford to leave their jobs and children in order to fly or drive long distances to the points on our country’s shrinking map of remaining clinics.

Others face the artificial barriers imposed by their gestational age: the schedule of “trimesters,” invented and imposed upon our pregnancies by the Supreme Court justices who decided the Roe v. Wade case, is not a medical framework but one of legal control. It ensures that if someone’s pregnancy has progressed past a certain arbitrary milestone, my clinic (like the vast majority of other U.S. clinics) is no longer able to see them. Regardless of the particulars, those of us with firsthand experience know the unthinkably cruel burdens people are sometimes forced to bear, all in order to undergo a 10-minute procedure that is safer than a root canal, or to obtain a bag of pills that are safer than Tylenol.

This is the context in which Partners in Abortion Care has opened its doors, and why the clinic’s creation has felt so joyful to so many of us — not just in Maryland or the Mid-Atlantic but everyone watching, everyone burning with that same rage Nuzzo jokes about, everyone in desperate need of a way to turn it into something productive. The Partners clinic, one of a tiny handful of all-trimester centers, will be a safe haven for the kind of care we dream of–trauma-informed, patient-centered care, for anyone, at any time up to 34 weeks of a pregnancy.

The clinic’s simple four-word name also functions as a perfect description of its founders: a team of expert reproductive health care providers, moms, and longtime friends. Nuzzo and Horvath understand deeply what partnership requires and what it can build, and — along with their chief operating officer, Kim Lee-Wilkins, RN, BSN, MBA, MHCA — they are putting the concept into active, direct, unstoppable practice. They know that organizing, collaborating, and community are the only tools we have in building as many lifeboats and escape hatches as we can.

Horvath and Nuzzo bonded over their shared professional purpose: helping other people navigate the complexities of pregnancy and parenting within a system hell-bent on making both feel impossible.

We start our conversation, over extra large coffees, with intros and credentials. Horvath is an OB-GYN with more than 15 years of clinical and leadership experience in abortion care. The taller and more soft-spoken of the two, she has the kind of dark hair and warm smile I would personally hope to see at an appointment involving a speculum or cervical dilator of any kind. Nuzzo is a CNM, a type of advanced practice clinician that is increasingly essential to abortion access. Her laugh is easy and frequent; there is often a wink in her voice, an unspoken “Can you believe this bullsh*t?” glimmer to her deadpan statements. In her seven years of providing abortion care, as a registered nurse and then as an advanced practice clinician, she has become one of the few midwives trained to do so through all trimesters of pregnancy. And she has long been ready for this terrifying moment.

Horvath and Nuzzo were co-workers first, crossing paths and building community at various local abortion clinics, but it was motherhood that brought the two women together in a more intimate way. Horvath, who has an 8-year-old daughter, would meet with Nuzzo for “kid swaps,” exchanging hand-me-downs: toys, supplies, and secondhand clothing to fit Nuzzo’s younger children. And as those mom-acquaintanceships borne of necessity and isolation often do, theirs blossomed into a deep and abiding friendship. Horvath and Nuzzo bonded over their shared professional purpose: helping other people navigate the complexities of pregnancy and parenting within a system hell-bent on making both feel impossible.

Most Americans who have abortions are already parenting at least one child — and, anecdotally, the vast majority of abortion providers whom I have met or worked with are parents as well. Motherhood and abortion are deeply connected in my life, as they are for many of my colleagues in reproductive health care or justice work. Many of the OB-GYNs, midwives, and nurse practitioners who make a living in abortion care also deliver babies and provide prenatal care to patients who plan to continue their pregnancies.

Horvath tells me that while she can say with confidence she’s good at the technical side of abortion care, yes, the part that involves being present and, as she puts it, “not shying away from those really hard moments,” is where both she and Nuzzo shine. “I think this care feels like more than just getting someone not pregnant anymore. It’s like allowing people to feel all of the things that they feel and to be a safe space to do that, and to be respecting all of the identities that people bring with them, all of the history, all the circumstances that got them there. And to be able to do that and do it well, is such a gift.”

Nuzzo agrees wholeheartedly. She has come to understand this work, she tells me, as its own beautiful, essential, specific vocation. “I am not a religious person … but this is a blessing; this is sacred work; this is a calling,” she says. “I can’t do anything else because this is the thing that I am the most good at. And I want other people to be the most good at this too. I don’t want to hold this by myself; I don’t want to be an island by myself anymore. So I’m so glad to also be doing it with Diane because I don’t think I could do it by myself.”

And abortion care work is never sought, received, supported or provided on an island. An abortion is just one part of someone’s story, and if providers are lucky, sometimes they’ll get glimpses of its other chapters. Nuzzo tells me about a former patient who recently reached out to her. The patient is happily pregnant, and one of the first people with whom they shared this joyful news was the person who’d performed their abortion procedure years earlier. One pregnancy ending, another beginning, lifetimes of parenting and building families and futures in community with one another: These threads are unbroken and unbreakable, and sacred to Nuzzo. Tears come to her eyes, as we talk about this patient and their circumstances, and the child that an abortion provider helped them to imagine, to protect, to dream and grow into a reality.

“It’s like, ‘You know what? I’m a mom, I know — we love our kids. Wouldn’t we want the best for our children? And if you determine that this isn’t the right time for you to have another child? That’s you being a really good mom.’”

“I find that when people know that you’re a parent … that is such a profound connection to have with someone. That we’re in this experience together; you’re having an abortion because you need one right now, but we both know that you love your kids and I love my kid, and we can talk about that,” says Nuzzo. “Somebody says, ‘I just feel like a bad mom.’ It’s like, ‘You know what? I’m a mom, I know — we love our kids. Wouldn’t we want the best for our children? And if you determine that this isn’t the right time for you to have another child? That’s you being a really good mom.’”

Horvath shares the sentiment. “I was doing abortions at Planned Parenthood when I was 37 weeks [pregnant],” she says. “And I remember walking in and being like, ‘Oh, I don’t know if I'm going to make people uncomfortable,’ and maybe there were people who were uncomfortable, but almost everybody was like, ‘Oh, hey, congratulations, when are you going to have a baby?’ I’m like, ‘Hopefully in two weeks!’ And I think there’s a continuum of reproductive experience. And so do a lot of the people I was talking to. And I feel like now it’s the same thing as I’m in practice… and I’m a parent. I talk to people about their kids because it’s a shared experience.”

I think of the nurse practitioners who performed my pre-abortion ultrasound, both mothers; the midwife who performed my aspiration procedure, whose youngest child I’d bounced on my lap and sung to; the assistant who — five months pregnant herself — administered my pain medication and held my hand and asked about my baby at home, as cramps rolled through my body and my second pregnancy ended. Nuzzo agrees: “One of my favorite things to talk about is parenting in providing abortions. I was pregnant during the pandemic, working in second and third trimester abortion care — I can’t imagine asking anyone to do this without having full consent to the process. … I just so deeply feel it every time I see a patient and they come to me and they’re just like, ‘I can't be pregnant.’ And I’m like, ‘I know.’”

Horvath knows that she and Nuzzo both feel a sense of responsibility to be present for the people who need their help. And sometimes, those people are children themselves. Horvath recounts a very young patient she saw at a previous clinic. It was a several-day procedure, she noted, because the patient was later in her pregnancy. “And we did her procedure, and she did great. And her mom was there talking about how proud she was of this, of her daughter. And I was thinking, My kid is only a few years younger than this person. And that was a huge thing to hold. And then this patient basically said that what she was looking forward to most when she got home was to just be a kid again. Just to be a kid. And I went into the office and just sobbed.”

“I want people to get good information about later abortion,” Horvath insists. “I want people to know that there’s folks like me and Morgan who are willing and ready and happy to care for them.”

Later abortion care is incredibly stigmatized, under-discussed, and misunderstood — even in “pro-choice” circles. Out of necessity, safety (for themselves, their patients, and their families) is still front of mind for Nuzzo and Horvath. The question of safety weighs heavily on any choice to speak about the clinic and the care they provide to their communities. “But if we’re not out telling our stories,” sighs Horvath, “there’s tons of people who will fill in the narrative with shit information.” If, as she points out, the narrative is already unfolding all around us — from the New York Times’ opinion section printing wildly inaccurate descriptions of the termination of an ectopic pregnancy as “delivering a baby” (it is, medically, not), to anti-abortion extremists being credibly cited by journalists with no reference to the violent crimes they’ve conspired to commit and the scale and methods of their harassment and abuse — then she should be working to counter some of its harmful propaganda. “I want people to get good information about later abortion,” Horvath insists, “I want people to know that there's folks like me and Morgan who are willing and ready and happy to care for them.”

Nuzzo and Horvath speak about the work of unlearning the stigma of abortion care after 12 weeks of pregnancy. “A lot of us even within the abortion-providing community are uncomfortable with later care,” says Horvath, “and it shows up in a lot of ways. It shows up in the way we talk about it and the way we talk to patients or about patients, little judgy throwaway comments, like ‘How could somebody not know they were pregnant?’ or ‘Gosh, they presented for care really late’ as if there’s not a plethora of reasons people don’t have access to good care early on, and how entrenched that is in our health care system and capitalism and all of those things. I don’t know that I thought those things necessarily [before I began providing later abortion care], but I hadn’t given them thought, if that makes sense. I was like, ‘Hmm, this isn’t the right job for me right now, or maybe when I’m older, my child is older,’ whatever. Then it occurred to me, I can’t just say that ‘this should be available,’ and I can’t just say ‘someone should do this,’ knowing that so few people [actually] do it. … I couldn’t keep saying that this should be theoretically available, but not do it myself. I have the skill set; I have the expertise; I have the heart and the drive to do it. I couldn’t not do it.”

Though neither Horvath or Nuzzo would ever self-identify as “businesswomen,” they’ve had to spend much of their recent time and energy on just that: business. The response they’re getting from their community is so affirming, the women say, but even with the outpouring of love, and the abundance of support — the $5 and $10 donations from broke abortion clinic workers, stay-at-home-moms, and college students; proceeds from the author and abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba’s sales of her artwork and T-shirts; an anonymous $20,000 mystery donor — the Partners clinic team has still had to take out loans and apply for grant funding in order to make this unimaginably expensive dream happen.

After growing the clinic sustainably (its operating costs are still largely community-funded), their next big task was to find vendors who were willing to work with them. They learned, quickly, to immediately disclose the specifics of their business upfront. Nuzzo lights up when she recounts their lucky initial consultation with a contractor, who responded with an enthusiastic “Anything to get an abortion clinic open right now, anything, you will be my priority project.” Nuzzo recalls being taken aback but pleasantly surprised when the contractor told them he was expecting a baby in August and, ”everything is so messed up right now. … Whatever we need to do, let’s do it.”

But nobody who is forced to deal with the finances or logistics of an abortion clinic forgets for one second what is at the heart of their battle with the booby-trapped, never-ending maze of bureaucracy (and its Final Boss, capitalism). This is the why behind all of the spreadsheets and grant-writing and endless meetings: their own pregnancies and children, the lives and the families they will help to nourish and create. Their patients, both past and future, and the lives and families being nourished and created at this very moment, as a result of the abortions they’ve provided.

It brings me immense comfort to realize, as I speak with these women, that my tangle of co-existing emotions about my abortion experience will likely make perfect sense to the generation of children we’re raising.

As moms who are reproductive health care providers, the partners speak openly with their children about bodies, about pregnancies, and about their work. Horvath has a daughter with whom she says she’s built an intentional foundation of openness. “The discussions we have about abortion are just on a continuum of discussions we have about babies and pregnancy and periods,” the physician says.

Nuzzo’s oldest is 5 and a half, with a firm grasp on the realities of pregnancy, bodies, and abortion. Nuzzo recounts a recent conversation with them, as she was tucking them into bed. “They said, ‘I want to talk to you about abortion care’ — they always call it ‘abortion care.’” Nuzzo smiles through the air quotes, bemused but clearly proud of her wise and warm-hearted kid, who then went on to announce: “It’s your job, and I want you to know that I think it’s good and bad … so it makes me happy and sad at the same time.”

Nuzzo’s child was able to put into words what so many adults struggle to articulate, even to ourselves, in large part due to our culture’s flattening of abortion into a moral or ethical binary, a political football, a talking point or slogan rather than what it truly is: a private and individual event, a personal and real part of a human being’s long and complex life. Like pregnancy, birth, and any other personal transition or medical event, abortion can be good and bad, happy and sad. I grieve and celebrate my abortion, and neither of these personal truths changes its necessity or my right to have had it. And it brings me immense comfort to realize, as I speak with these women, that my tangle of coexisting emotions about my abortion experience will likely make perfect sense to the generation of children we’re raising. The children who will grow up knowing their bodies belong to them, who arrive at reproductive age with a full and vivid understanding of sex, pregnancy, birth, consent, human rights, and of abortion — what it is, how it works, and its place in our communities and our lives.

Hannah Matthews is a journalist, essayist, and abortion care worker. Her work has appeared in ELLE, Esquire, Teen Vogue, Catapult, McSweeney's, and many other publications, and her book You Or Someone You Love is forthcoming from Atria in 2023. Follow her on Twitter, subscribe to her newsletter of abortion love letters, or visit her website for more information.

This article was originally published on