Life

The Bedtime Book That Rages Against The Dying Of The Light — Interview With Colin Meloy & Shawn Harris

One school of thought holds that if you read your child enough books about whispering bunnies and jaunty moons and going off to noddy-nod sleeeep land, they will succumb like cats to a ticking watch. Another school, populated by rock stars, asks: what if you don't try to trick them into dropping off? What happens when you enter the witching hour with them? This is the fantastical world of Everyone's Awake, a picture book written by Colin Meloy, The Decemberists' frontman, in dedication to his "ever-wakeful family," and illustrated in laser beams of color by Shawn Harris, a frequent collaborator of Dave Eggers.

"It's probably helpful to not only be told It is time to sleep, you must sleep, sleep now, which is sort of what all children's books for the most part do," says Meloy, author of the Wildwood series, a collaboration with his wife, artist and author Carson Ellis.

He mentions Bedtime for Francis by Russell Hoban, in which Francis has freakout that she can't sleep and is threatened by her father. "You're setting up this poor badger as it is to have sleep-related neuroses and anxiety for the rest of her adult life!" says Meloy. His teenaged son is not a sleeper. "There was a moment we were just like, I guess this is just how he does it, just being awake in the middle of the night." His 6-year-old, Milo, being a 6-year-old, also likes to forestall bedtime as long as possible. "I have my own issues with insomnia that is sort of anxiety-driven, like being on the road and the pressures of tour," says Meloy. "It can be somewhat of a boon to me to be like, you know what? Get up, do some sh*t. It's OK if you don't sleep."

Which sets up the book. It begins:

The crickets are all peeping.

The moon shines on the lake.

We should be soundly sleeping.

But everyone's awake.

At this point, the muted illustrations of a house over a lake are lit up with a special neon yellow ink Harris found "flipping through the Pantone books," he explains while perambulating around his house with earphones in, chatting with Meloy in splitscreen. "It looked like a light flipped on inside of the paper." He created the artwork by pre-separating the colors, and figuring out how the yellow would affect each spread. "If you're reading it in a dim bedroom at bedtime, that yellow still screams off the page."

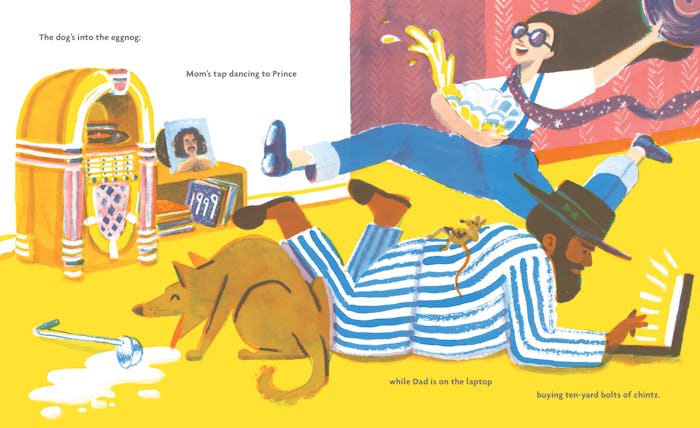

The book comes to life at this point. Characters come out of the woodwork to sing into broomsticks, play badminton, and make the kind of racket that seems louder by a magnitude when you are lying still with your head on a pillow, watching the ceiling and wondering what your neighbors are up to (juggling plates, no doubt). The story attains the kind of euphoric energy that my 3-year-old exudes once he is 15 minutes past his bedtime and running on backup fuel, shuttlecocks in his mad little eyes.

"The fount of creativity" comes from the same place as the energy stemming from "the witching hour," says Meloy, and shouldn't always be ignored. Anyway, he argues, sleeping through the night is really a modern invention. Centuries ago "you would wake up and you would eat and you would do something in the middle of the night. You're forever reading novels Russian novels where [it's the middle of the night and] they're like, '... and then we had dinner.'"

Our children are like Ludmila Ulitskaya in that way.

My tolerance for a child protesting bedtime is much lower than for my own Night Guy deciding to stay up and watch another episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, and this parental paranoia and double-standard weaves its way into the book ("will we be reduced into a shambling sleepless heap?" What happens if it's "forever everyone awake"?), but Meloy and Harris give kids the benefit of the doubt — staying up late looks like a ball, thanks to Harris's vivid bacchanal, which is littered with cultural Easter eggs for keen adults (Condorman ring a bell?) that in turn remind you how keen you were as a child to get to know about grownup things.

The sister is flossing her teeth and reciting Baudelaire, and even if your child doesn't know who that is, "you have an opportunity for the kid to learn from inference, which is great for reading comprehension," says Meloy.

"[It] was a fun challenge to provide that extra context because I think it's really important to, as a reader, not be afraid of books that we don't already know everything from," says Harris. "What's the point, you know?"

Now that the morning has come — Everyone's Awake is on bookshelves everywhere — Meloy and Harris are able to reflect on their partnership, brought together by Ellis's long-running "Kids' Book Kegger," held on Ellis and Meloy's farm in Oregon each year, a bacchanalia that has grown milder as everyone has aged and added children to the mix. "I credit Colin and Carson for making a hub where people can come together and hang out in a largely solitary field," says Harris.

Will Harris and Meloy work together again? "I don't know. Maybe," says Meloy from under a dark beanie.

Harris is less certain, earphones dangling out of frame in northern California. "Who's this guy again?"

Everyone's Awake is out now from Chronicle Books.

See Shawn Harris explain his artistic process for the book here.

This article was originally published on