Life

I Gave Birth While Incarcerated, In A Room Full Of Strangers

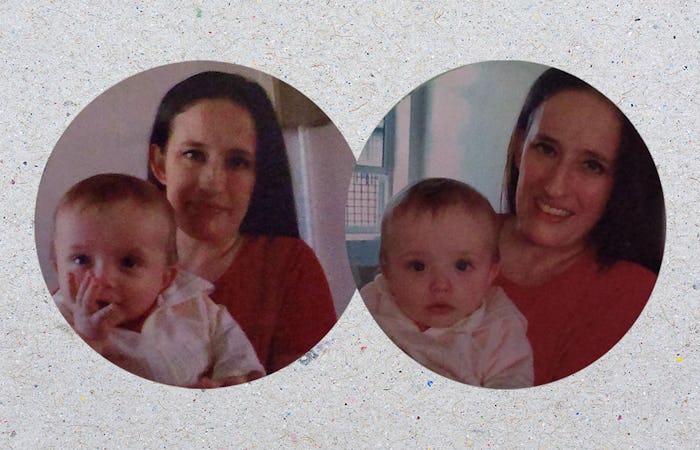

Sarah Murphy was living at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women, a maximum security prison, in Bedford Hills, N.Y., while pregnant in 2018. Murphy had a cesarean section in a hospital, then returned to Bedford Hills with her son three days later. Now a mom of three, she talks about what it was like to give birth while incarcerated, and how she recovered. As told to Danielle Campoamor.

As inmates, we all have chores, and mine was the mess hall. You don't skip out on your chores, and there's no maternity leave in prison. So the day I returned from the hospital I was moving tables and sweeping, mopping, and buffing the floor while I bled into my oversized mesh underwear. The bleeding continued for three months.

Before I was incarcerated, I was on a deferment program — a rehabilitation alternative to incarceration — and taking Suboxone, a medication used to treat opioid dependence. When I found out I was pregnant with my son, I was switched to Subutex, another medication used to treat addiction that's much safer for pregnant people.

Unfortunately, I relapsed. It was horrible. I knew I shouldn't have done it, and I felt so incredibly guilty that I willingly turned myself in. I was immediately arrested, then booked in the country jail, where I remained for three months before I was transferred to Bedford Hills.

I wasn't allowed to have Subutex when I was incarcerated, and instead was administered 30 milligrams of oxydcodone a day. The dose was significantly less than what I was consuming when I was on the deferment program, and I started to experience withdrawals.

You're not supposed to take somebody off of opioids, or anything like that, when they're pregnant. It's dangerous, and it can cause a miscarriage. When I was going through withdrawal I actually had to be transferred to a nearby emergency room twice. I thought I was going to lose the baby. Thankfully, I didn't.

I already had kids — twin girls — so I knew what pregnancy was like and what labor and delivery was supposed to be like. But when you're incarcerated, it's nothing like what it's "supposed to be." You have no power over yourself or your own body or what you do with your won child. There are rules for everything. It’s scary to not know when you can go to the doctor, or, if there’s something wrong with you, if someone is going to take care of it or take it seriously.

Still, some things remained the same. I was given prenatal vitamins every day. I was transported to my OB-GYN appointments regularly, and eventually saw a high-risk OB-GYN every week as my due date neared. And, like so many people who give birth, I had no idea when I was actually going to have my son. While I knew I was going to have a C-section — I had one previously, so that's how doctors and I had decided I would give birth again — I had no clue when I would have it.

Randomly, one night after dinner, a correctional officer told me to pack my things: I was headed to the hospital to have my son the next day.

I ended up having my son in a room filled with strangers I had never met before. It was scary. It was also incredible.

My family lived in Syracuse, about 4 1/2 hours away from me, so it was impossible for them to be there when my son was born. I was lucky, though. I was able to have someone call my step-mom for me, and she was able to drop everything and drive to the hospital. My mom couldn't be there, though, and I ended up having my son in a room filled with strangers I had never met before. It was scary.

It was also incredible. I mean, it's always a magical thing, when you get to see your baby for the first time. When I had my twins, they were 10 weeks early, so they had to be taken to the NICU immediately after they were born. I didn't get to see them or hold them.

I did get to see and hear my son, though. It was such a relief to hear him cry; to see that he was healthy. Because I was numb from the C-section I wasn't allowed to hold him right away, but the doctors did put him next to my face. He was near me, right away.

My step-mother was able to visit me in recovery — she was actually the first person to hold my son — and there were two correctional officers with me at all times. We spent three days in the hospital, although it would have been two if I hadn't of put up a fight. They wanted to send me back without my son, while he waited in the hospital an extra day for his circumcision, but I said there was no way I would be leaving without my baby. Thankfully, an officer was there who fought for me, and said that, for logistical reasons, like staffing and transportation, they couldn't allow me to leave without my son, either.

And then I was back at Bedford. I took my son to the nursery, then went straight to the mess hall to complete my chore. I truly think that's why I bled for three months; they had me doing heavy work like that right away. I would take a shower, get dressed, then sit down and bleed through my clothes. At one point I presented a pair of my bloody underwear with blood clots in it to the nurse, as proof that I was still bleeding significantly, but they just told me to drink water.

Bedford Hills is one of eight correctional facilities in the country that allow children born to incarcerated mothers to stay with them, and houses the longest-running nursery in the country. The nursery is managed by the volunteer staff of Hour Children, an organization dedicated to supporting incarcerated and formerly incarcerated moms and their children.

I know the day will come when my son asks to hear his birth story.

I was a full-time mom, so I was with my daughters up until I was incarcerated. I was really sad without them, so having my son with me made it a little easier. And the staff at Hour Children were great. They treated me like a person, and that doesn’t happen in prison; you’re treated like an animal, basically. So it was good to have people coming in and working with us who treated us like we were actual human being. Because we are.

They also saw something inside of me, and informed me that I was eligible for work release, a program that allows inmates to leave the correctional facility if they secure employment. Thanks to the Hour Children staff, I was allowed to enter the program and didn't have to stay in the prison anymore. In fact, I was only in the nursery with my son for a week. They gave me a job, they let me stay in one of their homes with my son, and they're helping me reunite with my daughters. They give me the space available so that when they come visit, and they have their own beds and everything. I get to actually be a mom now. I plan on staying here, in Long Island City, instead of returning to Syracuse, and am currently trying to secure an apartment through Hour Children so I can move them here, too.

I know the day will come when my son asks to hear his birth story, and I know that when that day comes the best thing I can do is be completely honest. I know, one way or another, he will find out regardless. I want to make sure that he can come to me with anything, and one way to help ensure that's the case is to be honest with him — with all my children — about what I went through.

And the truth it, it's a horrible thing, what I had to go through. I don't think I was given as many chances as a lot of other people. But I do believe that everything happens for a reason, and I think that I went through this so that I could be a better person. Now I can educate people on what incarcerated women have to go through, and if I can make some kind of a difference, I would love to.

Read the next piece from Not In The Plan, essays about the unforeseen elements of birth, and the ways people recover.

This article was originally published on