Life

Kentucky Might Be The First State With No Abortion Clinics

In the United States, there are currently seven states with just a single abortion clinic. An ongoing legal battle could mean that Kentucky is about to be the first state with zero abortion clinics, according to The New York Times. Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin, a Republican who's gone on record as anti-choice, has taken a hard line anti-choice stance since becoming governor in 2015. This January, after the first week that both the Kentucky state House and Senate were under Republican control for the first time in 100 years, Bevin signed two restrictive anti-abortion bills into law.

The first bill required that women not only undergo ultrasounds before having an abortion, but that they must also be shown the ultrasound photos and have them described in detail — even if they don't want to be shown or told about those ultrasound photos. The second anti-abortion law in Kentucky bans abortions after 20 weeks, making it the 17th state to ban abortions based on gestational limits.

As if getting an abortion in Kentucky wasn't already difficult enough thanks to draconian anti-abortion laws with no basis in sound medical best practices, the 1.5 million women over the age of 18 in the nearly 40,000-square mile state have exactly one abortion provider between them: The E.M.W. Women’s Surgical Center in Louisville.

The American Civil Liberties Union has stepped in for the E.M.W. Women's Surgical Center back in January, taking the state of Kentucky to court over the passage of H.B. 2, the state's oppressive ultrasound requirement law. But then Kentucky's sole abortion provider was given a letter "out of the blue" on March 13 from the state, telling the clinic it would lose its license in 10 days and would be forced to close, according to Dr. Ernest Marshall, the clinic's 66-year-old founder and abortion provider. On March 31, a judge issued a temporary restraining order preventing the closure of Kentucky's only abortion clinic.

The state cited that the clinic's hospital and ambulatory transfer agreements were "deficient," according to court documents. These agreements are required in case of emergency if a patient needs to be transferred to an area hospital. But here's the catch, as noted by The New York Times: The University of Louisville Hospital refuses to sign a transfer agreement for E.M.W. Women's Surgical Center. The hospital's current owner, KentuckyOne Health, includes two former Catholic health care systems who oppose the practice of abortion. KentuckyOne Health will no longer manage University of Louisville Hospital as of July 1, where the hospital will fall under the management of University Medical Center, according to Louisville Business First.

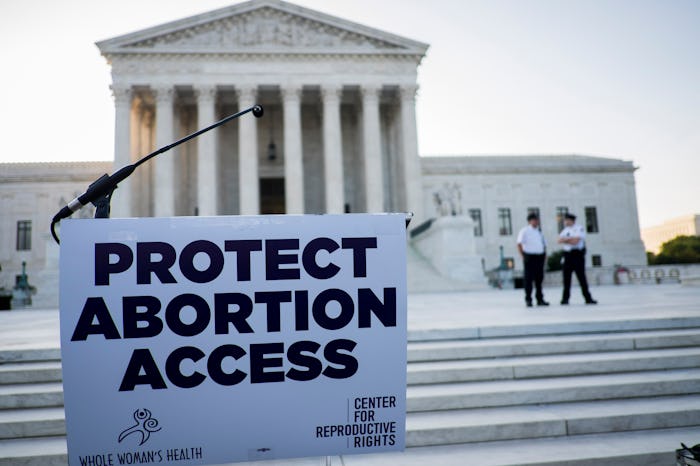

The clinic's licensing — and thus, its potential closure — is on hold pending the outcome of the clinic's latest legal battle with the state. A trial has been scheduled for September. Anti-choice proponents are watching closely to see how a 2016 Supreme Court ruling could be applied in this case. Reproductive choice advocates however, remain hopeful. Brigitte Amiri, writing for the ACLU blog, notes that Whole Women's Health v. Hellerstedt set a clear precedent preventing an "undue burden" for women to access abortion care.

But the Constitution is on our side, and this is an easy case. States cannot close an abortion clinic — especially the last remaining clinic — for a bogus reason. Just this past June, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt that a Texas law, similar to Kentucky’s, that required clinics to have business arrangements with hospitals served no medical purpose and, in fact, harmed women by decimating access to abortion in the state.

While it seems like it might be an open and shut case for E.M.W. Women's Surgical Center, there are no guarantees until a final ruling is issued one way or the other. Until then, the 1.5 million women in Kentucky who could need an abortion will have to travel to the state's sole clinic, with no certainty that it will still be there for them in the future.