Black Breastfeeding Week

"White Women Think I'm Lying:" Why I Face Backlash During Black Breastfeeding Week

My poem goes viral every Black Breastfeeding Week and so does the hate.

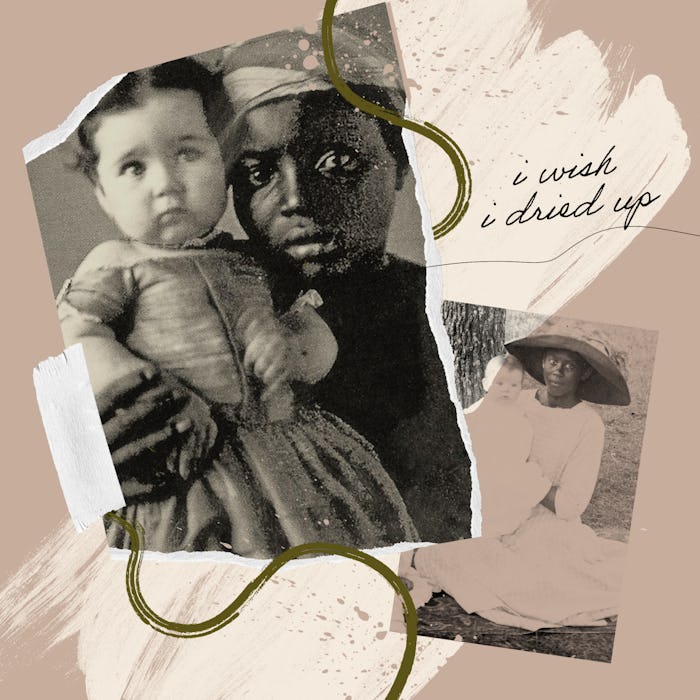

I wish I dried up

I wish every drop of my milk slipped passed those pink lips and nourished the ground

Where the bones lay

Of my babies

Starved while I feed their murderer

I wish I dried up

So the missus babies would dry up too

And be brittle

So I could crumble them to dust

Return them to the ground

Where all children of my bosom lay equal.

“You made this up!” is one of the many responses I repeatedly get on social media to a poem I wrote about the historical trauma of breastfeeding. Well, of course, I made up the poem — but the sentiment and the historical context of the words are real. As someone well-versed in the history of Black women in the U.S. and as a Black breastfeeding mother, I know that every choice I make as a Black parent is fair game for backlash. When my poem makes its rounds during Black Breastfeeding Week, I don’t expect anything less.

There are cultural implications for Black mothers in how and why we chose to parent in a world that devalues Black life and the people that birth Black life. Since I wrote “I Wish I Dried Up” in 2017, it has gone viral on multiple social media platforms every August. It’s often used by non-Black birth workers and lactation consultants to start a conversation about Black breastfeeding. The story in this poem comes from a centuries-old voice — the collective voice of Black women whose stories were lost to the whitewashed retelling of history that excludes Black women and makes both their accomplishments and suffering invisible. The people who dismiss and disbelieve the history the poem speaks to can somehow believe in the beauty Shakespeare captured in his sonnets, but they can’t believe the horror I captured in mine.

The backlash that I’ve gotten over my poem is the same backlash that has also been given to Black Breastfeeding Week in general. The refusal to face that the wellness of white families often came at the destruction of Black families speaks to society’s guilt and anger over the fact that we won’t forget the legacy of slavery and wet-nursing, and that we have the audacity to declare that our children get to take up space in this world. The centuries-old voice was muffled because people like to take a pillow and apply pressure over the mouth of Black women’s perspectives in history, so I coaxed it out. I asked it to be louder, and it shouted a scramble of words, tears, and grimaces.

The angered responses to this poem tell me that many white women think I’m lying. They want to deny the role they play in the terrorism that is white supremacist delusion, and the legacy left from the enslavement of Black people in America and how the residuals touch everything, including breastfeeding. As someone who practices the spiritual tradition of Black people in the U.S., ancestral reverence and storytelling are major parts of how I help to keep the tradition alive, and I capture that call as the primary inspiration for my writing.

“The person in the picture didn’t say that.”

“No one said that.”

These are the typical responses I see by white people in the comments of each shared post of my poem, but the heinous mistreatment of enslaved Black women is not some myth. Black women like Margaret Garner, who was born into slavery and killed her own child rather than send her back to slavery, were not uncommon. Despite media depictions of Black Mammy figures, enslaved Black women did not gleefully raise white children — the same people who would grow up to see them as less than human, as worthy of abuse, and not worthy of rights. In the prophetic tradition of Black women knowing, Black girls and women could clearly see their fate the first time they were handed a white child to care for, or a white infant to nurse, while their own infants went hungry.

What these deniers, full of fear, or hate, or both, miss is that Black people don’t want to trade places. We want restitution, and for our experiences to be acknowledged.

On plantations and in houses across the nation, many white women were bystanders when their spouses, brothers, fathers, and cousins raped Black girls and women, and sometimes Black men and boys. They were not only bystanders to the abuse, they perpetrated much of the abuse. The idea that a Black woman could have the audacity to dream herself away from that trauma and wish her captors to feel the wrath of their own hatred is both an American wet dream and nightmare. Authors and directors make speculative fictions about the role reversal, and hate groups create real terrorism and justify it with that very fear. The resistance to this fear causes denial. What these deniers, full of fear, or hate, or both, miss is that Black people don’t want to trade places. We want restitution and for our experiences to be acknowledged.

In response to my poem, white women have told me I don’t know what I’m talking about, and that I’ve never breastfed, though I breastfed all three of my children. They’ve dismissed the traumatic experiences of Black women wet nursing their enslavers’ babies by saying that people who breastfeed produce more milk when they are feeding more than one person. There are records, however, of the infants and children of enslaved women dying due to being malnourished and being given breast milk substitutes because their rightful supply was all given to a white child. This trauma has been passed down through generations of Black mothers who speak about our histories and our hurdles. When we speak about Black motherhood, however, our experiences are questioned or silenced.

Perhaps the most frustrating response comes from the white women who declare that we must let go of the past and unite to become one. The past still haunts us. The afterlife of slavery still lends to disparities for Black breastfeeding mothers and to the high Black maternal and infant mortality rates. A call to forget the past is a marker of repeating it. If we must be haunted by the truth to incite change, then it’s a horror that we must all confront. My poem, backlash included, stands as a doorway to that confrontation.

This article was originally published on