Life

The Case For Letting Children Explore The Dark Through Picture Books

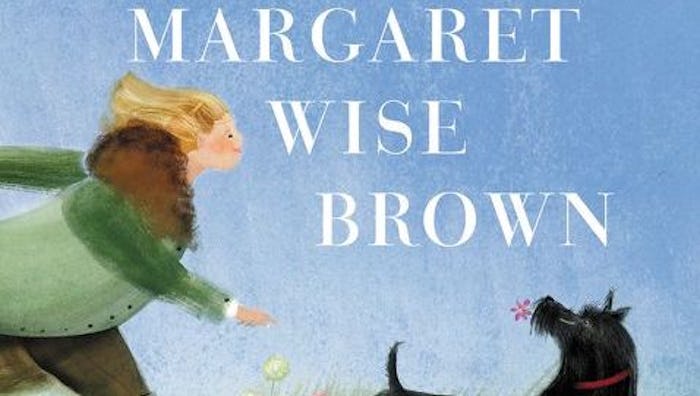

While many nurseries host copies of Goodnight Moon, the iconic green and orange cover tucked among board books and burp cloths, few people know the iconoclastic author behind the work. In a new book, The Important Thing About Margaret Wise Brown by Mac Barnett, young readers are exposed to the quirky author, the kind of person who once skinned her own pet to wear.

In the midst of introducing us to the author and her predilections, the book takes a quick swerving detour to describe a librarian at the New York Public Library during the time period that Brown was publishing.

“Anne Carroll Moore was a conservative.

She liked books that were darling and innocent,

Like she thought children should be….

And the book did not get a place on a shelf in that library

Nor in many other libraries besides,

Because lots of librarians listened to Anne Carroll Moore.

She was important.”

While few people today would pick up Goodnight Moon and label it anything other than innocent (okay, there’s the “It’s creepy” camp), in her time Anne Carroll Moore labeled anything Brown published as “truck,” and rubber-stamped it with relish, deeming it unacceptable for her treasured audience of children.

Kids in school aren’t huddling away from the fear of the atomic bomb, but they’re under their desks anyway — hiding from school shooters, tucked away in closets, and poised to toss staplers at intruders.

But if you’ve spent time with any child in the past, you know that few of them, even at a young age, are darling and innocent. They shove cookies in their mouths when confronted, ask questions about dead bodies, and generally cause more chaos than one would picture at a staid mid-century library. Yet even in the 1950s, surely children being served by Anne Carroll Moore needed to hear about the weirdness of life more than the anodyne. The threat of nuclear winter had kids huddled under their desks, yet this one librarian decided on her own that the little fur family was just too much for young minds to handle.

In another page Barnett muses about Brown herself:

“There are people who will say a story like this

Doesn’t belong in a children’s book

But it happened…

And isn’t it important that children’s books

Contain the things children think of

And the things children do,

Even if those seem strange?”

Expanding beyond the world of picture books and into middle grade and YA, a debate has been raging over the past decade of whether the literature we give to children is too dark, too scary for kids to read on their own. Kids in school aren’t huddling away from the fear of the atomic bomb, but they’re under their desks anyway — hiding from school shooters, tucked away in closets, and poised to toss staplers at intruders.

There are still Anne Carroll Moores out there — librarians, educators, and even parents who feel that the content in young adult and middle school books are inappropriate for young eyes. In a 2011 Wall Street Journal article entitled “Darkness Too Visible,” Meghan Cox Gurdon decried the genre, lamenting that the books available for teens had become too grim and focused on the darker sides of lives. A passionate comments section ensued and the conversation has been reinvigorated over the past few years.

What librarians like Anne Carroll Moore and writers like Meghan Cox Gurdon miss is that the darkness seen in children’s books is not always seen through a window. For some children, the situations represented on the page may showcase some of the same painful pieces of their own lives. Barnett’s assertion that it is important for children’s books to reflect the things children think of and do, is never more pressing than it is in troubled times, with children who don’t feel safe at home or at school, and need to see that reality reflected back to them to know they are not alone. "I think it's important for me to write about kids as they are and not as adults want them to be," Barnett told Romper previously.

Lives don’t work the way most books do... They can end suddenly.

As I develop my collection for my middle and upper school library, I try to keep in mind that simply keeping books about hard things away from kids doesn’t mean that I can keep those things from happening. Furthermore, for those who aren’t experiencing the darker side of life, reading fiction builds empathy, so crucial in a continuously harsh and coarsened world. The librarians who are invested in keeping books where difficult things happen from kids are doing all of us a disservice. It begins with weird books like Margaret Wise Brown’s and continues all the way up to those with “mature content” being kept off library shelves.

Mac Barnett ends the book on the sad fact that Brown passed away at 42. “Lives don’t work the way most books do,” he writes, “They can end suddenly… lives are funny and sad, scary and comforting, beautiful and ugly, but not when they’re supposed to be.”

Even if Brown’s books didn’t always get to the root of this, the importance of works like hers resonate. Books where you can’t quite predict what will happen when you turn the page, the way that we can never be sure what will happen when we step out the door in the morning. Parenthood is the same way, scary and comforting, beautiful and ugly. We and our children need books that expose us to the full range of life experiences, even when they’re scary and formless.

“But sometimes you find a book that feels as strange as life does,” Barnett writes, “These books feel true. These books are important. Margaret Wise Brown wrote books like this, and she wrote them for children, because she believed children deserved important books.”

Guiding our children, whether we parent them or act as trusted adults, often requires us to teach difficult lessons. Sometimes a book can be the most important thing in the world, if it helps a child feel less alone. In the end, Barnett says, “The important thing about Margaret Wise Brown is that she wrote books.”

In a scary, formless world, sometimes that’s what matters.