In the middle of the night, a bedroom window creaks open, and a woman enters. She grabs the child sleeping from the bed, wrapped in a blanket, and sneaks out the window. They fade into the distance under the moonlight. The child’s parents wake up in the morning to find their child, whom they adopted, gone forever. The child’s birth mother had kidnapped them in the dead of night, never to be seen again.

True life? Far from it. Typical Hollywood portrayal of adoption? Absolutely. Whether its an unexpected bitter custody battle years after the adoption such as in Halle Berry’s Losing Isaiah or the aloof and distant expectant mother in Juno, the “birth mother as bad guy” trope is a popular, yet harmful, theme in Hollywood adoption stories. This negative trend was most recently tackled by Celeste Ng in her novel Little Fires Everywhere, centered around a brutal custody battle over an abandoned baby. Ng’s story will be made into a film by Reese Witherspoon, adding to the already heavily-laden adoption misconceptions present in film. Through villainizing and trivializing biological parents, or through erasing them from the narrative altogether, such as in Anne of Green Gables, the film industry has a reputation for missing the mark on the importance of biology to adoptees. The no-strings-attached orphan is perhaps more palatable for the average viewer, despite being such an inaccurate portrayal of adoption.

Another scene, this one in reality, paints a different picture. A baby boy sits in a high chair covered with streamers, as a cake is placed in front of him. His family crowds around to take pictures as he explores the cake and finally smashes it. His birth mother and adoptive mother both smile as their baby boy reaches this monumental milestone — his first birthday. They pose for pictures and smother him with kisses. Plans are made at the end of the party to visit again, and tears are shed — every separation is difficult. Yet everyone involved in this child’s life knows having his whole family around him is what is best for him. This is love.

Adoption is complicated, it is fraught with loss and heartache. It can also be beautiful.

This little boy’s birthday is a picture of open adoption in action. His birth family — mother, aunts, grandparents, cousins — want the same things that his adoptive family wants. For him to thrive. They work together to achieve that. The reality of adoption is far removed from the drama Hollywood portrays.

Adoption is complicated, it is fraught with loss and heartache. It can also be beautiful. Today, approximately 60 to 70 percent of domestic U.S. adoptions are open. A growing number of foster care and international adoptions also include contact or visits with the child’s biological family. Contrary to media tropes, most adoptees in open adoptions feel that the openness helps them process their complicated stories and feel whole. Instances of kidnapping or harm to adoptees by their biological parents after adoption are almost unheard of.

Elisa Joyce, adopted transracially from Senegal at age 5 in 2000, says that she avoids the adoption genre in entertainment, which inevitably comes loaded with racial innuendo.

“I wish Hollywood would stay away from it in general, or at least consult more adult adoptees before they portray it in any light, good or bad. I feel like they only show it from the sibling or parents’ side. The movie The Blind Side brought up an awkward situation for my family. People would make sort of snide comments about how lucky my parents were that they adopted three black kids that excelled at sports… but our family was athletic so we just grew up active and healthy,” she says, describing herself foremost as a nerd. “I scored a 28 on my ACT and people were surprised.”

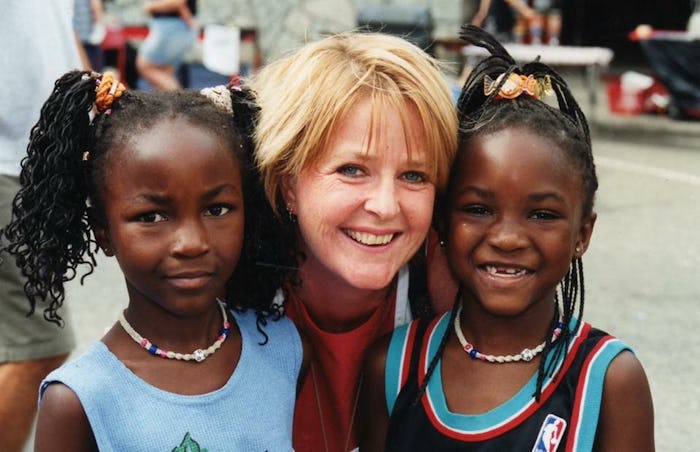

Recently, some in the entertainment industry are listening to the concerns of adoptees such as Elisa. This Is Us, NBC’s hour-long drama, currently in its second season, is tackling the intricacies of adoption with more accuracy that Hollywood has ever done before. The show, featuring a transracial adoptive family (white parents with a Black son), has intentionally hired writers of color as well adult transracial adoptees in an attempt to improve on previous adoption storylines.

One particular scene echoes Elisa’s experience with academics. Randall’s adoptive grandmother remarks that she is surprised that he is her only grandchild to make it into an elite private school. She buys him a basketball for a gift repeatedly, despite the fact that he has no interest in the game. She makes assumptions about Randall based on his race, just as adults in Elisa’s life made about her. Randall’s character struggles with overachieving and fighting for acceptance.

This makes sense to Elisa. “I feel like I always have to be the best at everything, and it has proven to be a curse because it really destroyed me in college,” she says. Other adoptees echo this sentiment, as well.

Another common theme in the film industry is “white adoptive parents as saviors.” Whether by celebrities adopting themselves, such as Angelina Jolie or Madonna, or by the portrayal of adoptive parents in movies like The Blind Side, the belief that adoptive parents are somehow “rescuing” their children is harmful.

This is not a recent trend, as the savior theme is central in Les Mis as well. Valjean is framed as a hero for taking in an urchin. The complexities of Cosette’s birth history are overshadowed by the actions and emotions of her adoptive father.

As author and adoptee Nicole Chung notes in her essay for Catapult, “When I was growing up, I couldn’t find any stories about adoption that spoke to my experience. If it did pop up in the rare novel or film, it was usually portrayed as a reward after great hardship, as in Annie, or used as sensational fodder for stories like The Face on the Milk Carton. I never saw the uneasy if unfinished drama of the everyday; I never saw adoption depicted in a way I could recognize.”

Hannah Davis, adoptive mother to two children, tells Romper, “People have these ideas about adoptive parents that they've picked up from TV. So they talk to me like I'm some noble person for adopting. This bothers me, because it diminishes my kids when people act like they are in our family as some kind of charity project. Our children are a blessing to our family, not because of what we've done, but because simply because of who they are.”

Elisa echoes her concerns, “Like the ‘white savior’ thing is so big in Hollywood right now, and it makes my mom and dad cringe because it gives other people this false image about them and our family dynamics.”

The entertainment industry is about just that, entertainment. Dramatic adoption stories with a protagonist draw more viewership, despite the fact that these stories are inaccurate, and harmful to adoptees. The inclusion of adoptee voices in This Is Us is a big step forward for Hollywood, but there is still a long way to go to eliminate negative portrayals and misrepresentation of adoption in the film industry.