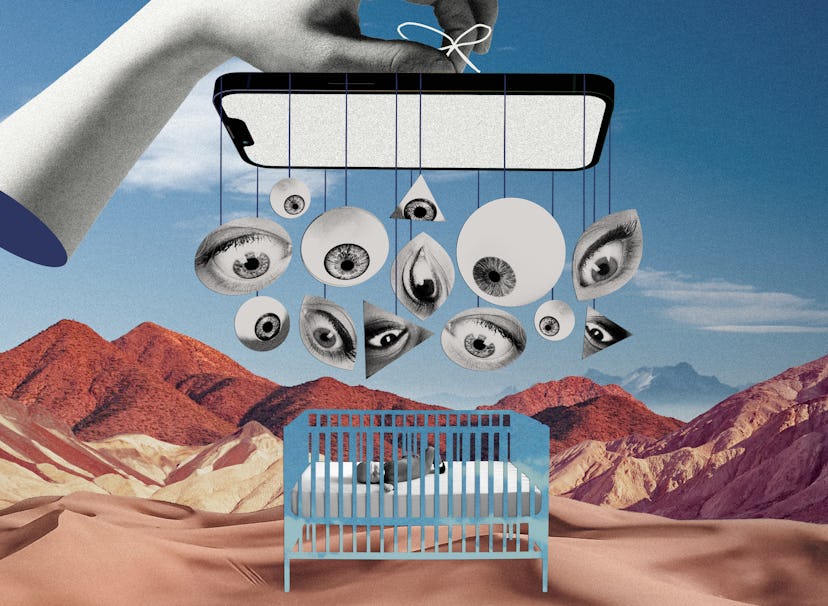

The Surveillance State For Babies

Where The Wired Things Are

Sleep monitors, smart cribs, AI-enabled strollers: These days, your baby’s nursery might resemble a surveillance state. But is that a good thing?

One recent pre-dawn morning found me walking blearily down the hall, leading my preschooler back to bed to fix an offending blanket that had fallen off and doing a series of complex calculations in my foggy brain. If it was 3 a.m. now, and her older sister, thankfully still asleep in the top bunk, woke up at 6:30 a.m. to start her day, and the baby slept until 7 a.m., the preschooler would get at least three solid hours of sleep before the general noise of the morning roused her. That would all be scrambled if the baby woke up earlier, and if the baby woke up later, that would mean his afternoon nap would also be a little later, and then we’d need to do some NASA-level coordination to figure out who was getting the first-grader from the bus stop as at least one of her two younger siblings snoozed.

Blanket fixed, I climbed back into my own bed where, for the next hour, my brain did loop-de-loops, different scenarios shifting and dissipating in my mind’s eye. Wouldn’t it be nice, I mused as I drifted off, if I could just plug all the inputs into some program — my family’s various sleeping habits, and sniffly noses that need middle-of-the-night blowing, and next door construction that interrupts naps — and spit out a plan that optimized for a low-stress, Zen existence?

Of course, spend enough money and there are versions of this very thing on the market right now: Technology that promises to streamline your life as a parent, calm any latent anxiety, and reassure you that you are doing what is best for your child, however unsure you may feel. For years, there have been audio and video monitors, and more tech-enabled ways to track what we used to just write on a piece of paper (food intake, poops and pees, hours of sleep). But in the last decade, and particularly the last few years, this nursery tech has taken off at warp speed.

We’ve hurtled ever closer to a time when a thin layer of tech exists between nearly every interaction we have with our children.

These promise not only to optimize sleep but in many cases to keep your baby safer. There are high-tech monitors that use computer vision to track your child’s sleep patterns at night, then provide tips to get you to that Valhalla, the 12-hour-sleep night. There are algorithmically powered apps that promise to decode your wee one’s cries, and tell you if he is tired, fussy, or hungry. There are smart bassinets that jiggle and wiggle your child into an optimal sleep state (you know the one). And this year’s Consumer Electronics Show was abuzz with chatter about an AI-powered stroller that stops the wheels before your baby rolls down the hill and can be set to a “rock-my-baby” mode so you can sit on that park bench, hands and feet free, as junior is soothed into complacence.

While much of this stuff is out of the financial reach of the majority of new parents, experts assured me that it is only a matter of time before sensors and computing technologies become small enough (and cheap enough) to be just about everywhere. Less than three years has passed since I reported my book, Baby, Unplugged, which investigated the intersection of parenting and technology, but even in that short time, during which generalized anxiety got a nice booster shot courtesy of Covid, we’ve hurtled ever closer to a time when a thin layer of tech exists between nearly every interaction we have with our children, the layer promising a nebulous notion of “optimized parenting”: simpler nighttimes, easier mealtimes, idealized babyhood.

Each new tech product seems to be the 21st century realization of LEGO’s original slogan: “Only the best is good enough.” Best for baby, best for parent. But is it, really? Is it really safer for baby? Can it actually help parents relax, secure in the knowledge that technology is making them better, more trustworthy, more seasoned versions of themselves?

“Anxiety disorders are extremely prevalent in the postpartum period, but beyond that, anxiety is a normal human response to needing to care for a new human and never having done it before,” Dr. Amanda Kimberg, M.D., a psychiatrist at Duke Health who specializes in child and perinatal psychology, tells me, “and it’s nearly universal that parents feel some level of anxiety at the time of having a newborn. Absolutely, these tech products can take advantage of that experience, those fears.”

Kimberg is skeptical not just that marketers are taking advantage of a sleep-deprived, vulnerable population but that many of the products themselves — specifically those that monitor and track — disrupt perhaps the most important part of new parenthood. “In those first months, the goal is for parent to get to know baby,” she says. “Tracking the exact numbers of ounces a baby is taking, the exact number of poops each day, these things aren’t necessary to ensuring the baby’s health and well-being, and can distract from the emotional cues that the baby might be giving to the parent.”

“It starts in the nursery, but it goes on with devices that track your children and this need to know everything about everything, which is not really what being a parent is about. Being a parent is about doing your best to grow healthy humans, mentally and physically.”

As for the effectiveness of sleep monitors — one of the most appealing tech advances for anxious parents — experts by and large say to nix them in the nursery. “For a healthy child, these high-tech monitors are probably not going to alert you to anything specific, and there are false alarms, and a trip to the ER probably poses more harm than sleeping without it,” says Nancy Cowles, executive director of Kids in Danger, a nonprofit that focuses on product safety for kids.

As a new parent, I took great comfort in something my pediatrician told me when my eldest was a newborn: that my daughter would not have been released from the hospital had she needed any sort of daily monitoring. And the American Academy of Pediatrics’ most recent sleep guidelines state firmly to “avoid the use of commercial devices that are inconsistent with safe sleep recommendations. Be particularly wary of devices that claim to reduce the risk of SIDS or other sleep-related deaths. There is no evidence that any of these devices reduce the risk of these deaths. Importantly, the use of products claiming to increase sleep safety may provide a false sense of security and complacency for caregivers.”

Most professionals I spoke to said there is no one-size-fits-all approach to technology in the nursery. Some people will get comfort from tech, and the important thing was being mindful and thoughtful. But again and again experts also cautioned me that the mere presence of technology was, more times than not, a barrier between parent and child. “It starts in the nursery, but it goes on,” Cowles tells me, “with devices that track your children and this need to know everything about everything, which is not really what being a parent is about. Being a parent is about doing your best to grow healthy humans, mentally and physically.”

And as any parent of older children can tell you, this process doesn’t really come with shortcuts, tech-enabled or not.

While some program may yet come to market that will analyze my children’s disparate sleep patterns and spit out some optimal program for me to follow, likely it will serve merely to reroute my sleepless middle-of-the-night strategizing to my phone, where I’ll plug in and crunch data through the wee hours. Maybe, for a small sliver of time, that’ll result in all of us getting more sleep. But the time I spend with the data is time I could spend tucking in blankets, and wiping snotty noses, and getting to know my magical little children even better. It’s the most basic stuff of parenting. And why try to hack that?

Sophie Brickman is a writer, reporter, and editor based in New York City. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Saveur, The San Francisco Chronicle, and The Best Food Writing and The Best American Science Writing anthologies, among other places.