books

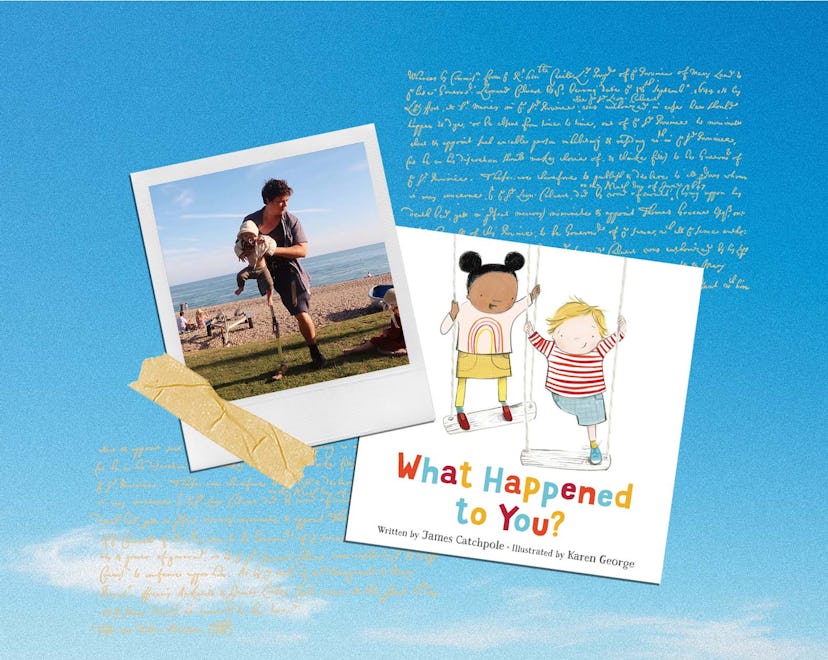

James Catchpole Has One Leg, Two Kids, And A Very Charming Children’s Book

What Happened To You? helps kids navigate disability with grace and humor.

“What happened to you?” It’s a question — an obtrusive one, mind you — that author James Catchpole has heard his whole life. Catchpole is a through-hip amputee and his experiences of being questioned this way inspired two children’s books: What Happened To You? and You’re So Amazing, co-authored with his wife, Lucy Catchpole, who is also disabled (“More children than working legs,” as their Instagram bio puts it).

In addition to being parents of Ismene, age 8, and Viola, age 4, the couple also runs a children’s literary agency based in Oxford, England. They advocate for diverse and accurate representation of disabilities in media, and work to break down stigma in real life through their books and online presence. Romper spoke with Catchpole about the question that spawned his first book and still plagues him as an adult, and how his disability made the transition to parenthood all the smoother.

Let’s talk about your book, What Happened to You? The main character, Joe, is based on your own experiences growing up as a kid. In the book, when one child asks Joe this question (“What happened to you?”), the floodgates open and more kids start coming from every direction. Is that the typical scene, or is it an amalgamation of lots of moments?

I mean, it’s a particularly bad pile-on, isn’t it, that one? So if Joe’s on the playground at school, the kids in his class aren't going to ask him every day. They all know him. They’ve got used to him. And for him, he’s just one of them. So why would they ask?

But all the other kids in the school who don't know him, and any kids he sees in the park, are going to stare. Every single one of those children will stare. And sometimes for a while, none of them will ask because that's human nature in crowds. But the second someone does then that spell is broken and they all want to know, and they do all gather around and wait to hear the answer. It goes from Joe playing happily on his own to being interrogated by a mob very, very quickly.

The way Joe handles all of the other kids’ wild guesses — like whether his leg was stolen by a burglar or eaten by a lion — with a simple no, gives permission to kids like him who are reading it to simply not have to answer. It made me wonder how often, if ever, that permission is granted to children with disabilities, or how you came to give it to yourself?

That’s exactly it. I never had that permission. I don’t think it occurred to people to give me that permission. Were they asked, I don't think my parents would’ve said, “You have to tell people.” But it took me until my 20s — really, it took me meeting Lucy, who is disabled in a much more conscious way because she became disabled as a young adult. I was already feeling uncomfortable with the idea of being asked this question by strangers, but only through Lucy did I realize that no one has a right to know. Children learn at some stage. They don’t run up to a man they don't know at the playground and say, “Where's your hair?” if he doesn't have any, right? I mean they might do that, that happens, but at some stage, they learn not to do that.

It’s just that with disability, we encourage the opposite. We actively encourage children to go on and just ask, which is a very strange and contrary culture as far as I’m concerned. It just seems like a way of inculcating everyone with the belief that disabled people don’t have the same right to privacy as everyone else, which is just a form of othering, I think.

Do you feel like your disability prepared you to be a parent?

Disability does prepare you for being a parent. It prepared us both because I think for a lot of people, having their first child might be the most dramatic thing that’s ever happened to them. It might be the first time their body has done anything severely difficult and out of the ordinary. Maybe things go wrong, and that comes as a real shock. Maybe they had a plan for how things would work out and it didn't turn out the way that they expected.

We don’t have any of those expectations as disabled people. Certainly Lucy doesn’t, with the nature of her disabilities. So we thought long and hard about the risks, which were considerable. But for someone who’s in bed most of the time and who lives with really severe constant pain and has done since the age of 19, having a baby, getting it out, those are big things to consider.

We had to think about all that very carefully. We didn’t have any expectation that it would all go to plan. We expected it might be a dumpster fire in all sorts of ways. So the fact that it went OK, the fact that the elective cesarean went the way we hoped it would within reason, and then at the end of it, what we had to cope with was sleepless nights and poo everywhere, that’s a walk in the park, isn't it? That’s not a problem. Everything’s a bonus after that.

Disability prepares you for the utter loss of control in your life, which also is what having a first child can be like. Suddenly everything’s only vaguely within your control. Disability and being a new parent are both the enemies of spontaneity. Spontaneity goes out the window with both. So if it’s gone out the window already, then there’s no great adjustment. It’s just all gravy as far as I'm concerned.

Your tagline about having “more children than working legs” made me wonder how people react to you and Lucy both having visible differences, and parenting together, compared to if only one of you was disabled.

This is a subject that we’ve been talking about since we first met, about people’s responses to disabilities and their different responses to different disabilities. If you have one leg and you run around on crutches, then you’re quite visually arresting. And as long as you move fast, then the association is generally one of heroism. People are often telling you how amazingly you are doing. And then if you put a baby in a sling on your front, then it’s heroism plus a halo — you get a saintly heroism. I can remember women crying and then coming over to tell me how much they were crying, which is nice. I mean, you can’t do much with it, but thank you, I’m glad you're moved by the sight of me walking with my baby.

Disability prepares you for the utter loss of control in your life, which also is what having a first child can be like.

For Lucy as a wheelchair user, I think she found having a baby on her lap had this amazing redemptive effect. We use this phrase "supercrip" — I get to be a supercrip all the time because if I walk around quickly, I’m a poster boy for disability. Wheelchair users, especially with a lot of pain? Less supercrippy. Kind of the opposite, right? You tend to get the pity rather than being called anf inspiration.

But then if you put a baby on the lap, then that’s Lucy’s one chance to jump into that redemptive, inspiring bracket. Not that you'd necessarily want to be in that bracket, but it’s better than being pitied. So that changes the dial for her completely. And then us both together, goodness. When I'm out and about with Lucy, and I'm wearing my leg instead of my crutches — that leg takes away all my supercrip stuff because I walk very slowly in my leg — I think we probably looked like two people who were in an awful car wreck but have nevertheless had a baby or maybe kidnapped a baby from somewhere.

As long as they don’t ask you how you got the baby.

Yeah, exactly. But the children, they overturn an awful lot of narratives for both of us. I’m a through-hip amputee, which means there's nothing left of one leg. And so I get this thing that sometimes people with bits missing on their lower half get: “Well mate, can you still have sex?” I got that rom the guy in the post office one day. I'm like, “Well, with you now? No.”

For me, the children answer that question. And for Lucy, they probably do something similar. The presumptions and narratives that people have around disability are so pernicious and hard-worn that having a baby on your lap, or having a couple of girls running around with you as you go out, immediately switches them off.

You had to think so deliberately about all the aspects of pregnancy and birth. How did that translate into all the daily tasks of parenting once the girls were born?

Well, you’ll have noticed that our Instagram bio is, “More children than working legs,” which is a fair summary. I have one working leg. I have a robot leg that I keep for when I need to change a lightbulb or every time I unload or load the dishwasher. But if you’re a through-hip amputee, then you run around on crutches rather than legs. So this is my normal mode of transport and that’s what I’ll be using when I go and get the girls from school in a bit.

Lucy has two legs, but she has to be in bed almost all the time. She probably describes herself as a mostly horizontal parent. An interesting thing about the way we’ve always had to parent, and we knew this would be the case before we got involved in all this, is that in the valley of the people with very few legs, the one-legged man gets to do all the practical stuff, you know what I mean?

I was always going to be the nappy changer and the cook and the cleaner-upper and the laundry man and all that. And that sounds like a lot, but it feels like 50% because all of the rest is so crucial. There’s something wonderful about having another parent who literally can’t do the majority of that, but therefore has the brain space to do all the rest of it so well, meaning the comforts and the wisdom and the education. The small one is 4 and she’s reading now, and it's not a brag about her, it’s a brag, if anything, about Lucy. That’s probably an actual advantage in some ways in having one parent who is always where you left her. The children know where she is all the time and teaching them to read is something that they can do together.

During the pandemic, when we were forced to homeschool, Lucy had to teach the older one her letters, and the younger one was 1.5 and was just listening in. And so now she knows her letters and she can read books and it’s gone in partly by osmosis and partly because that’s one of the things they can do with their mother. Whereas with me, they get to run around outside and kick balls and climb trees and all the rest of it.

There’s so much to explore at the intersection of disability and parenting. Is there anything you want to share that you haven’t had the opportunity to elsewhere?

One thing springs to mind, which is mother’s guilt. I think I’m speaking for Lucy in this, but one of the things that she knew she would have to do very early on is to make a conscious decision just not to go there at all. Not to express any sort of feeling of regret that she can't do more than she can as a parent. It’s so important, isn’t it? That you don’t apologize for who you are to your children. I don't think that was an urge that she had to fight particularly. I think she was very clear on it, always, all the way along.

This is the wonderful thing about parenting with a disability: Unlike anyone you’ve met in your whole life — including your own mother, your own parents — your child has no expectation that you could ever have been any other way. They have no model in their head for how you might be different. And so they accept absolutely your limitations as long as you don’t go around apologizing for them.